A photographer rekindles his love for his city and his craft after discovering the lost art form of tintype photography

—

I discovered photography, almost accidentally, when I had to fill a course requirement for my high school Art Regents program. Up until that point, painting had been my main focus, so a photography class could have quickly been filed in the same category as my pottery class. It was just another box to check for graduation and by no means a priority or passion.

My attitude immediately changed after my first class. I discovered that photography wasn’t just about pointing my camera lens toward something and clicking a button. I was tasked to create images based on my point of view, my personal lens, separate and distinct from the mechanical lens of my camera. I was inspired by how much I was challenged as an artist to express myself in a new and unfamiliar way.

But the process of creation didn’t end with pointing and clicking, even when done with an inspired eye. I had to practice discipline, restraint, and discernment. It was the 90s, before digital photography allowed for hundreds of images to be shot, reviewed, sorted, kept, and discarded in a matter of minutes. Film was expensive, so shots were considered carefully. And the process of bringing those shots to life was lengthy and even backbreaking at times.

While my friends played video games and socialized, I spent endless hours in a dark room developing my shots (and crossing my fingers that even one of them would produce something that would justify the effort). It was a long, boring, tedious process. But one I returned to again and again. Because as arduous as it was, one perfect shot made it all worthwhile.

My love for photography never waned or wavered, and I pursued it in college at the Fashion Institute of Technology and through taking jobs at the School of Visual Arts and camera shops like K&M Camera in downtown Manhattan (where I met lifelong friends who have also gone on to have successful photography careers).

Making pictures was my world.

Eventually, I would land a job at Harris Publications as a photo editor where I would spend four years working on magazines like King, Revolver, and Guitar World, all the while building a freelance career that would eventually support me fully.

By that time, digital photography was king, and client demands didn’t allow for the slow and deliberate process of making images by hand. The work was exciting, taking me all over the world and introducing me to thousands of celebrities, musicians, and sports figures, some of whom I only knew through posters on the walls of my teenage bedroom or album covers in my music collection. I was living the dream!

The problem, though, was that I was an artist, and feeling fulfillment as an artist required a certain amount of challenge, stretching, inspiration. I loved and continue to love to photograph musicians and celebrities (I’m still waiting on that call to shoot Tom Waits), but I was desperate for something fresh.

What I didn’t expect was that ‘fresh’ meant going back in time to the 1850s and re-discovering a process that I was at one time more than enthusiastic about leaving behind.

It was at a local Renaissance fair that I saw a man dressed as a pirate making wet plate tintype images in a tent. Wet plate photography is an entirely handmade process with origins dating back to the 1850s. Metal or glass-plate negatives are sensitized, exposed, and developed on-site using a portable darkroom. It’s art, science, and magic rolled up into one medium. I was mesmerized by what I witnessed.

Sometime later, I started exploring the craft on my own. I built my first darkbox out a cardboard box and researched the process of making chemicals necessary for creating my images. As soon as I developed my first plate, a fire reignited in my soul. I traveled back in time 20 years, and I was suddenly a teenager standing in my high school darkroom.

I was falling in love with photography all over again.

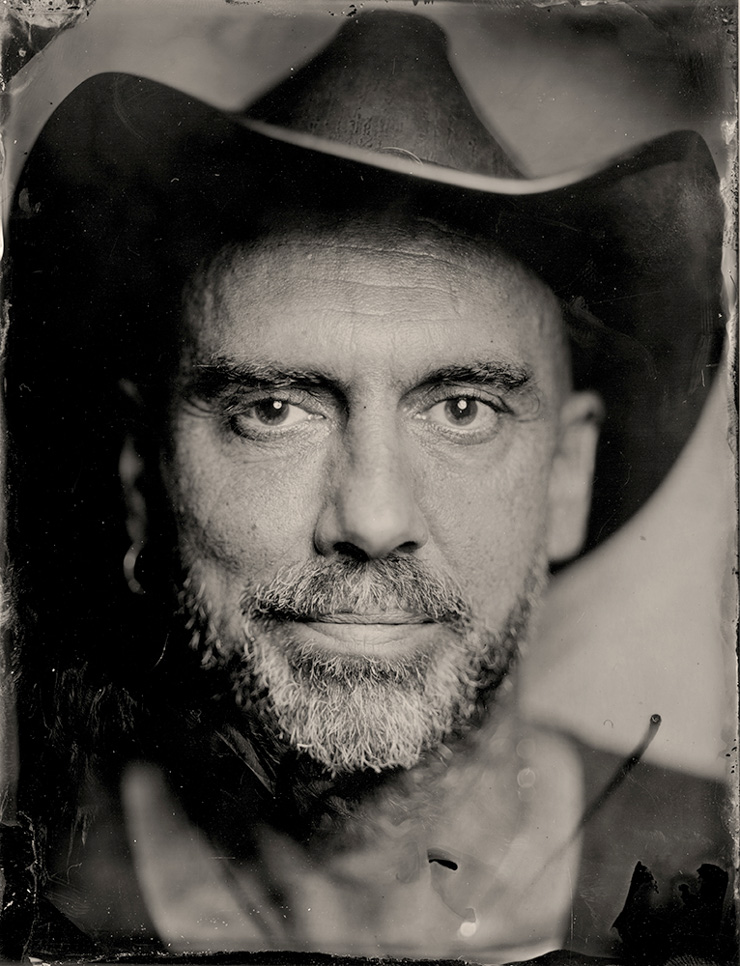

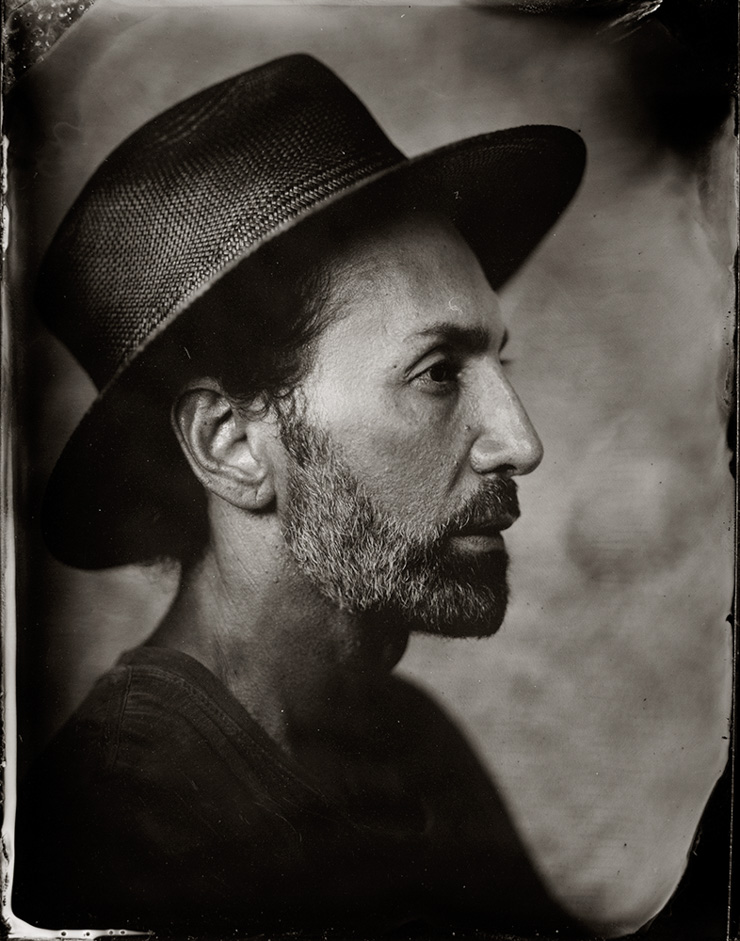

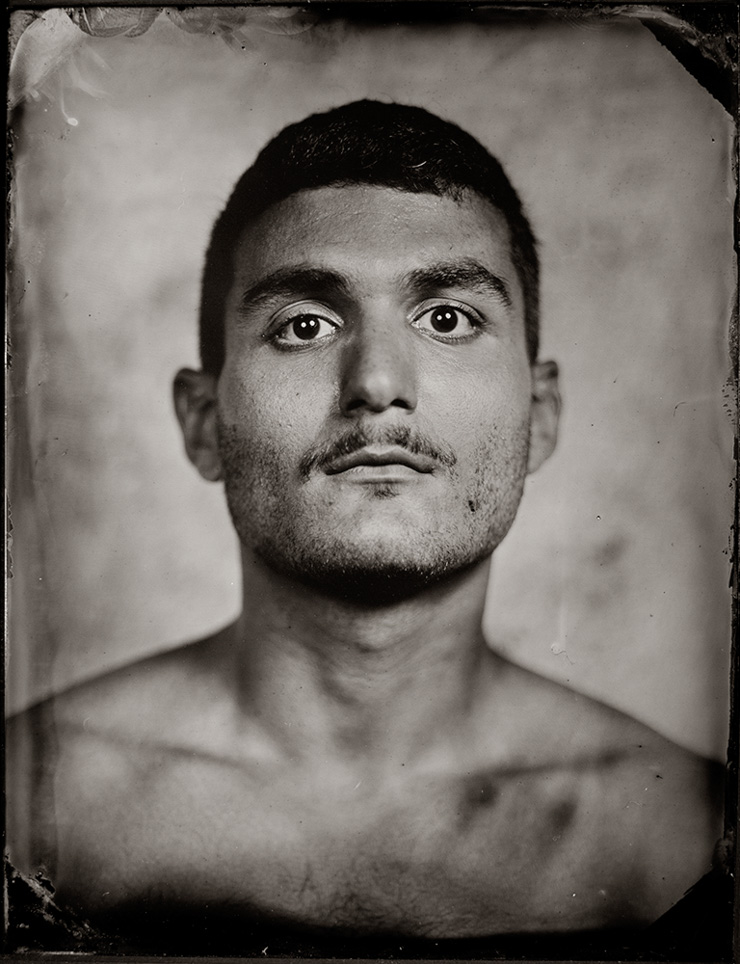

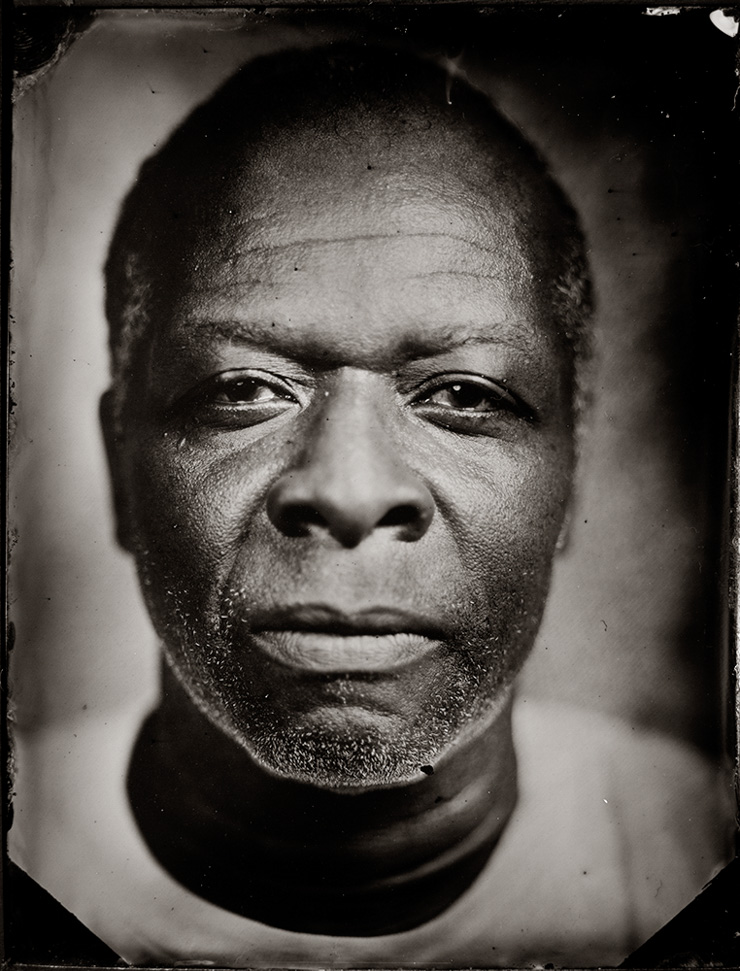

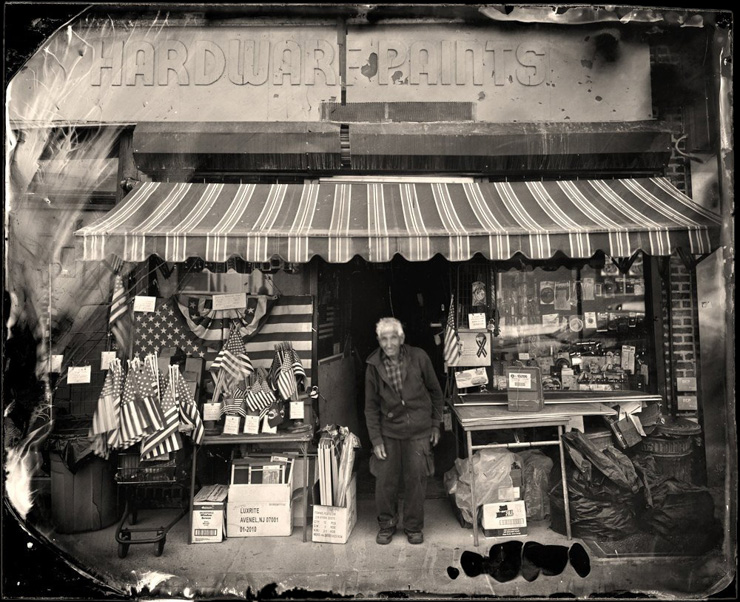

Not long after that first experience with wet plate, I found myself dragging a large format camera and wooden darkroom (that I built myself) through the gutters of New York City, painstakingly making handmade images in the streets. My plates absorbed all the dust, grit, and raw energy of the city.

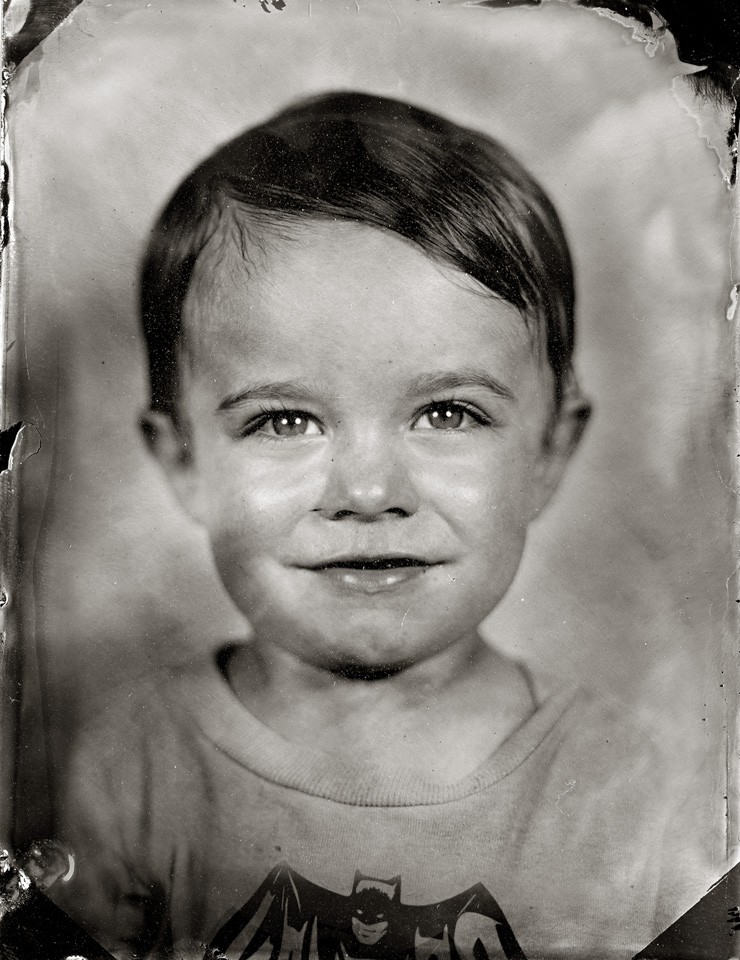

This process is poetry to me. The texture and detail of each plate can’t help but spark the imagination of the observer.

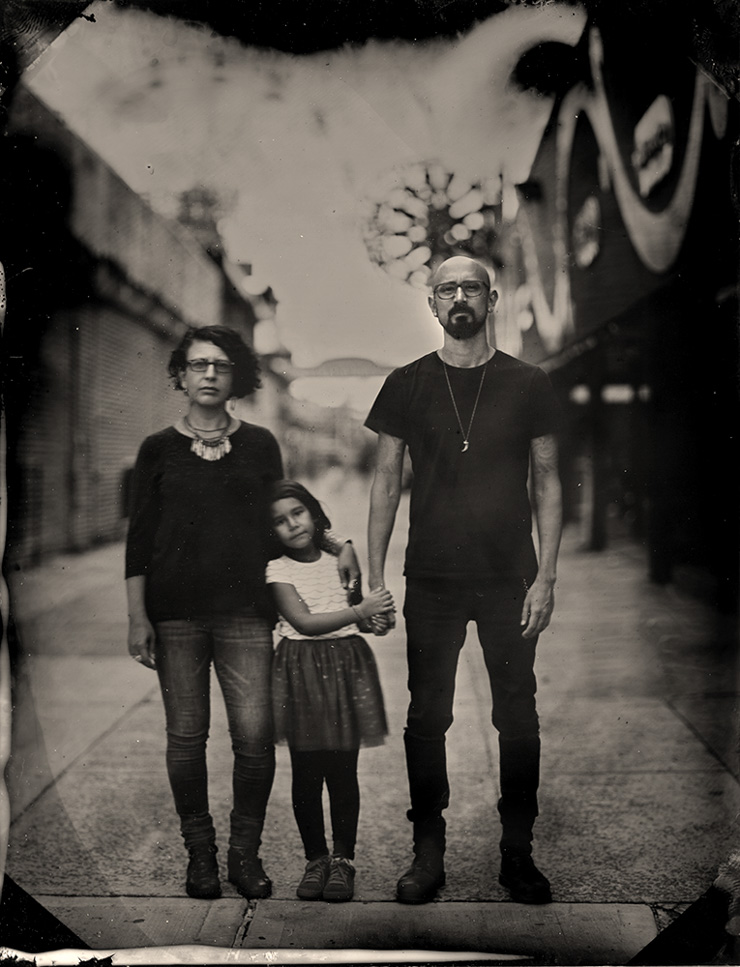

In a time marked by instant digital gratification and relentless self(ie) expression, this process slows life down—it slows me down. It inspires me to dive deeper, to explore further. It reconnected me with my native New York and opened my eyes to the beauty of the changing (and disappearing) city I loved as a kid. And now, running my pop-up tintype portrait studio on Prince Street in Soho, I get to connect with the beautiful stories of strangers in private portrait sessions, making one-of-a-kind heirloom images they’ll cherish forever.

Even though I’m humbled by the demand of the process of wet plate photography, I take great pride in what I’ve been able to create. And I feel thrilled to have the privilege of sharing my work with the world.

Maya Angelou famously said, “Success is liking yourself, liking what you do, and liking how you do it.” By all outside accounts and opinions, and based solely on my commercial work, I am a successful photographer. But I would encourage everyone to heed Ms. Angelou’s words as I have, as inspiration to continue to go after their dreams and strive for success in a way that feels meaningful for them, not just according to the rules of convention. Connect with the creative in you, and know that happiness and success lie in the pursuit of that connection and expression of your creativity.

View the Gallery; tap any image to enlarge:

You may also enjoy Bright Lights, Covid City: Broadway in the Dark by Dan Lane Williams