For jazz legend Jack DeJohnette, music is a deeply spiritual experience

—

Jack DeJohnette is the kind of jazz musician who almost makes me wish the word “jazz” would dissolve for a moment — not for long, because I love it too much. But maybe just long enough that people who don’t identify as jazz fans would be lured into the multiverse of sounds and styles, rhythms and colors that DeJohnette produces seemingly without effort, and hear it as the universal music it is. Crisp rolling thunder from the bass and snare drums, splashes from the cymbals that can sound like spring rain falling on sassafras leaves or a tin roof, and the timeless resonance of what could be a Tibetan brass bowl or temple bell. But that’s only his percussion entourage. DeJohnette’s first instrument was the piano and he still plays a number of keyboards, including a delightful melodica that can lend a childlike glee to the mix.

And what a mix it has been. Over the span of forty-five years, DeJohnette has shared the stage and recording studio with legends ranging from musical mystic John Coltrane to the electric jazz innovator Miles Davis (on his epochal album Bitches Brew); from Sonny Rollins to Sun Ra to keyboard deity Keith Jarrett. In all that time Jack has played on more recordings than any jazz drummer — as leader, co-leader, and sideman — but he had never won a Grammy until 2009 when he was awarded Best New Age Album for a solo CD of ambient music called Peace Time. How intriguing that this master of endless invention and complex composition was singled out for the kind of music more suitable for meditation than for dancing in your head.

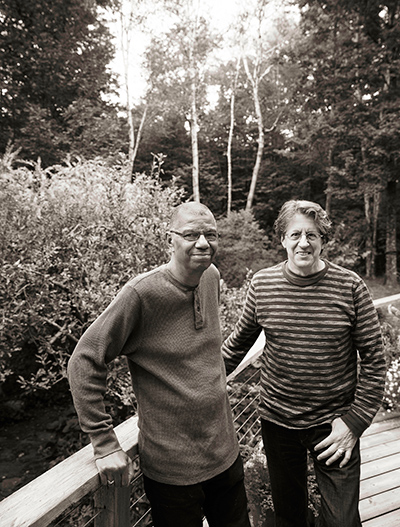

As a jazz writer, I had followed DeJohnette’s career almost from the beginning, but now I had begun to wonder about an aspect of Jack’s persona that I had maybe overlooked: his spiritual side. So I decided to sit down with Jack not only to discuss his multidimensional career, but also to find out what energies — physical and metaphysical — he draws on when he’s making music. And I wanted to learn how that music expresses Jack’s best, innermost self. I began by asking what precisely happens within him when he’s playing, whether in the recording studio or before a live audience.

“Music can transform you, and stimulate your feeling of being at one with everything — which most of the time we are, even if we’re not conscious of it,” DeJohnette says.

“And it doesn’t matter what instrument you’re playing. It could be your voice, a bass, or guitar. But when somebody plays it, something else happens in the connection between the fingers and that instrument. It opens up the consciousness to what I call the Library of Cosmic Ideas.

“When we play live for an hour or ninety minutes and we feel like we’ve only been up there for five minutes, we transcend the concept of linear time. We go right to the source where there is no time, and everything is happening simultaneously. And when you’re playing with an audience, rather than an entertainment, it’s a communion of souls who are there to inspire and be inspired by the music. You can feel it in the audience and you can feel it on stage. You can see the energy lines. The audience is very important to the resonance of the music.”

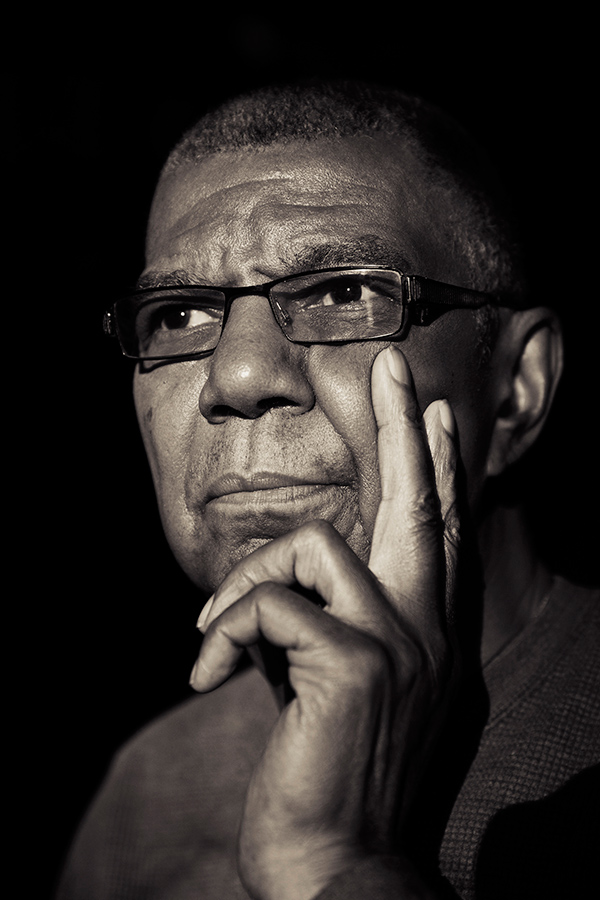

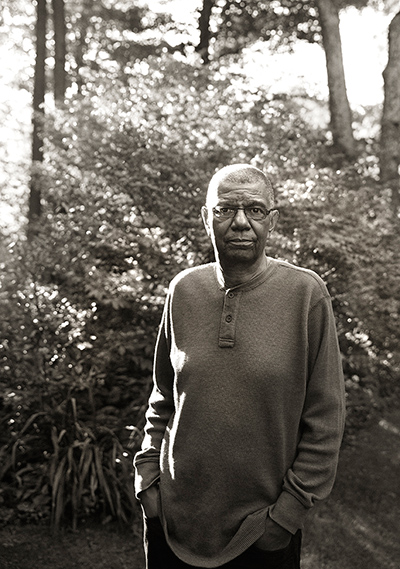

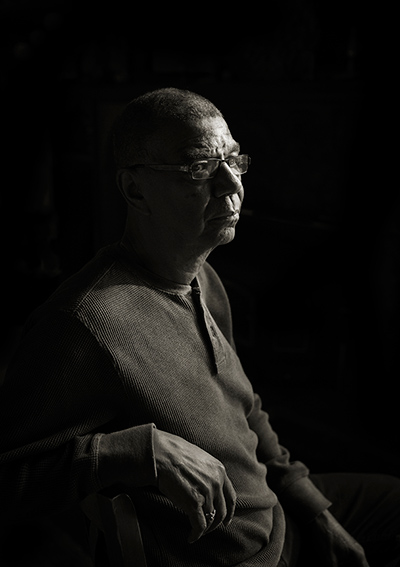

Relaxing at the kitchen island that connects with the spacious living room of his home in the hills above Woodstock, New York, DeJohnette is a trim-looking 72, with a warm smile and an unfussy attitude. When I ask him to elaborate further on what he experiences while playing, though, he is careful in choosing his words.

He doesn’t think “spiritual” is quite accurate, yet he knows that something is happening that can’t be defined in standard musical terminology.

“There’s some kind of ‘otherworldly’ — just to use that term — sense that I’ve tapped into other dimensions of existence. It wasn’t just me playing, but I was being assisted by either guides or other souls—a connection to other realms of existence, shall we say? It’s not just the ego “I” that’s doing it. It’s sort of a cooperative situation. You sit down to play and you don’t know what’s coming. They may know before you execute it, but in that nanosecond an idea comes out, or a phrase or voicing comes out. Voicing a chord can have a ‘spiritual’ effect, just that combination of sounds.

“Music is related to the spheres, the planets. The earth has a certain frequency. The sun hums. I tune into all of that. Keith Jarrett does — he channels, too. You’re aware that you’re working with other entities, other consciousnesses.

“When I sit down at the drums or the piano, it’s a discovery, it’s an adventure. Music is sound sculpture.

“You can create soundscapes just like painters create landscapes. Even if you don’t have it recorded, it’s not lost. I believe it’s heard or seen on many different levels. Nothing ever dies; everything is infinite. We’ve been taught a watered-down version of what ‘time and space’ is, that we’re in a three-dimensional reality, which we are not. We’re in a multidimensional reality with potentials that may seem remarkable to us — but these potentials are quite normal from an interplanetary or galactic point of view.”

DeJohnette’s reference to landscapes isn’t accidental. His wife of 47 years, Lydia, enjoys making art, and several of her semi-abstract paintings brighten their lively, raw-wood home. And when I ask Jack where he places himself on the spectrum of jazz drummers — ranging from the propulsive athleticism of Elvin Jones, who played in Coltrane’s celebrated quartet, to the finely shaded drumming of Tony Williams, who anchored Miles’s classic quintet before Jack took his place — he chooses a metaphor from the realm of art.

“I think of myself more as a colorist than just a drummer — a drummer who colors music like a painter, with shading, dynamics, and electronics. I have an electronic percussion module, although I use it discreetly. I approach electronics from an acoustic point of view. It’s just another palette.”

Then maybe it shouldn’t have come as a surprise to me (although it did) to learn that the first percussionist who influenced him was not one of those legendary names from the jazz pantheon, but Vernel Fournier, a drummer’s drummer who played on a best-selling album with Ahmad Jamal. “Vernel had taste,” Jack says. “Leaving space. His use of time and space and harmony and melody was fantastic.”

DeJohnette’s appreciation for subtlety, for “leaving space,” is part of the secret of his longevity, both as a leader and as a drummer who is in constant demand by top-flight performers from Sonny Rollins to Paul Simon. By emphasizing coloration, shading, and tonality, he is able to conserve energy — which he can tap in abundance to play as hard and fast as any rock drummer. He is helped in this by a regular yoga practice that also keeps his body flexible.

“One of the things I have worked on and still work on is getting in a space where I have to expend the least amount of effort to get the maximum output. Being conscious of breathing, like in yoga — being in the right balance of tension and relaxation. I talked to Sonny Rollins about that. He said a lot of people who do yoga get dressed up in outfits, but there’s something very spiritual about yoga that you work toward through the breathing — getting oxygen to those places in the body that may have blocks. I use that same concept when I’m at the [drum] kit. I feel like I’m riding a wave, an energetic, creative wave. I feel like I’m being carried by the creative consciousness. I hear Miles in my head sometimes, or I hear Coltrane. I think that corroborates that we never die.”

When we had spoken earlier about death, DeJohnette made it clear that he takes a metaphysical approach to life as much as to music. “I believe that we are infinite,” he said.

“We go through the process of birth and death, and death is just a mechanism by which the soul departs the physical body. But only a portion of that soul is in this physical body. People talk about life after death and immortality. We are immortal already. Some people believe that once you pass away that’s it — it’s darkness. But we’re reminded of the fact that we continue after we leave this body every time we go to sleep and have dreams. The things that happen in those dreams: you can bilocate from one place to another, you can fly. The astral body is free, and the creative mind takes what we deal with in our everyday life and puts on a play. It can help us or frighten us, or make us reconsider our views of things.”

As a young man Jack read books about astral projection, and one Sunday afternoon he decided to try it out for himself. “I took a nap and I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to go outside of my body.’ And sure enough, I fell asleep and my astral body went up to the ceiling and I was looking down on my body on the couch. But then I thought, ‘Holy shit, how do I get back there?’ You’re supposedly connected by a silver cord, so I communicated to my physical body and got back in. Sometimes I do that in dreams too. I get so excited just imagining all the different dimensions, all the humanoid species that are and that have been. There’s so much more to us.”

DeJohnette’s appreciation for the unity of life extends to the world of nature as well. “Trees and rocks and animals have feelings,” he says. “When you go out in the woods, you feel at one with them — looking at a flower or feeling trees. I say ‘thank you’ to the trees because they’re like brothers or sisters who sacrificed their lives to build this house, to give us shelter or the instruments that I play. There are so many connections, so many things to be grateful for, because everything is interconnected.”

This brings us to a discussion of the healing power of music.

DeJohnette reveals that his grandmother took him to services at the Christian Science church in Chicago, where he grew up. “At the time I didn’t know how spiritual that was,” he says of the teachings of Mary Baker Eddy about healing with the mind and through prayer. Although he never actually joined the church, the philosophy predisposed him to the idea that we can be healed by methods other than standard medical procedures and drugs.

While DeJohnette was still in Chicago (he moved to New York City in the ‘60s before relocating upstate), he had the chance to hear John Coltrane’s Quartet on many occasions. Some critics initially labeled Coltrane’s explosive saxophone playing as “hate music,” mistaking the fierce energy in his sound for anger. DeJohnette sees it differently. “Intensity, passion, and love were all there. It wasn’t angry, it was just so powerful. It was like going to church.”

Indeed, one night when he was listening to Coltrane, someone in the audience went into a kind of ecstatic state. “Trane started playing and this guy just went — like the Spirit hit him! They had to carry him out. It was not unlike an African healing ceremony.”

Years later, DeJohnette observed just such a healing ceremony in Dakar, Senegal, that went on for four days. “The drums are well respected there. And I saw a guy who had lost his memory. Some spirit had entered him and he couldn’t remember people. Other people who had had similar experiences and had been healed were there for support. I had become friends with the master drummer’s sons and they let my wife and me sit in the center of the ceremony. The drums were playing in 6/8 rhythm, slowing down and speeding up, and women were dancing along with the rhythm. And in the middle of the fourth day, the guy snapped out of it and recognized people again. That’s the power of rhythm and music.”

Although he feels that all the music he plays can have a healing effect on listeners, Jack specifically set out to create music to facilitate Lydia’s vibrational healing practice, resulting in Peace Time and an earlier album, Music in the Key of Om.

“I used to have a problem when I went to a spa to get a massage and some of the [background] music they played had people noodling too many notes, and it wasn’t relaxing at all. Music should take the stress off of you. So I went into an altered state when I made this CD, to see if it would relax me — and it put me into a zone. And a lot of other people have had the same response. Some people have used it to help put their kid to sleep, or when they were healing from some kind of illness. I use it when I’m on the road because it helps me go to sleep.”

A friend of Jack’s who works as a nurse convinced a local hospital to play both of his ambient CDs in the hallways and rooms, with the result that the attitudes of patients in hospice or recovery there improved markedly.

Another way that Jack evokes the spiritual is by responding in the moment to everything that happens when he’s playing.

One of his earliest concerts that I reviewed took place in 1977 at Joe Papp’s Public Theater in Manhattan. During a quiet moment in the show, the bass player’s amp started to emit a loud, irritating feedback hum. Some bandleaders might have waited for the noise to stop, or just ignored the distraction and played over it. Not Jack, who, as I wrote, “started OM-ing on the same wavelength as the hum. Other band members joined in, and alto sax player Arthur Blythe tied it all up with a streetcorner bass harmony that brought laughter from the audience.”

When I retell that story to Jack, he wails with laughter himself, then matches it. “I look at it as theater sometimes. Recently in Europe I was playing with Joe Lovano and the bassist Esperanza Spaulding. Esperanza moved the chair she was sitting on and it made a loud squealing sound. She looked mortified and said, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry.’ And I said, ‘Move it again.’ And we built an improv off of that. So something she thought was a mistake, I thought was part of the music. But you have to be alert.”

Jack stays in the moment in even larger ways by playing with rising stars who are not only half his age, but also happen to carry the DNA of great jazz innovators — literally. His stellar new trio includes John Coltrane’s son Ravi (named for the classic Indian sitarist), and Matt Garrison, the son of Jimmy Garrison, who also played in Coltrane’s legendary quartet. Matt, wielding a customized five-string electric bass (his father played only stand-up), occasionally processes the sound through a laptop onstage, showing how far fusion music has come since the days of Bitches Brew. Besides tenor and soprano sax, Ravi also plays sopranino (a shorter version of the soprano that his dad made famous) that he is making his own signature instrument.

Instead of coasting, as a musician with Jack’s track record could afford to do, he is instead taking jazz to the next step, integrating acoustic and electronic sound, free-form and structured composition. In concert, Jack seems to take fewer solos than he hands out to his young bandmates.

But in a sense he is never really in the background, because every sound he elicits from his drum kit is adding some essential flavor — some coloring or shading, to use his words — to the unified whole.

“I’ve always been curious about mixing different things, like an alchemist,” DeJohnette once said. “Different genres of music have always cross-pollinated, but the rate is speeded up now.”

Given all that acceleration — in life and culture — I ask Jack how he maintains both his obvious optimism and his ability to keep generating new approaches to music.

“I believe that in our true natures we’re hard-wired always to come up with fresh creativity anytime we call upon it. That has been the conscious wave that has carried me when I play music. When I get there I’m in a magical space, where the level of listening is intense. That space means I’m home. I’m at one with the creative consciousness — whatever that is! I feel at peace. It’s very healing.”

New music sample:

Older music sample:

You may also enjoy reading The Mechanics of the Mind: How Transcendental Meditation Creates a State of Bliss by Barbara Ann Briggs