Elizabeth Lesser

Lessons of the soul

Interview by Kristen Noel, January 5, 2017, Woodstock, New York

Photographs by Bill Miles

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

Rumi

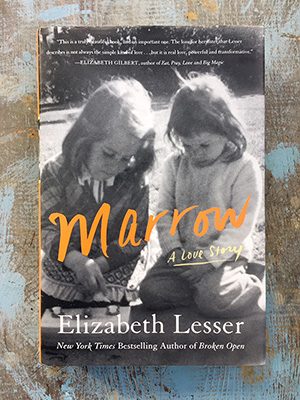

Kristen: Hello, my friend. Thank you for sitting down with us today and for welcoming us into your beautiful home. I feel very grateful to have the opportunity to be able to sit with you to discuss this book, Marrow: A Love Story. This is truly an exquisite book. I cried. I laughed. I highlighted passage after passage. I also felt myself crack open as I was reading it.

Even though I knew of your journey to become a bone marrow donor for your sister, as I was making my way through the book I realized that this was about healing on so many levels. It isn’t a book about dying. It’s a book about living and as you so beautifully said in the prelude, it is a love story.

Elizabeth: Thank you for those kind words.

Kristen: Before we dive in, I have to formally introduce you because I want to make sure that our audience knows of the incredible experience that you’ve had which has led to here. So, just bear with me as I gush about you a moment.

Elizabeth Lesser is a New York Times bestselling author of the book Broken Open: How Difficult Times Can Help Us Grow. She is also the author of the Seeker’s Guide, her first book that chronicles the years at the Omega Institute (the renowned retreat and conference center in New York’s Hudson Valley), which she cofounded in 1977 when she was in her 20’s.

Prior to Omega, she was a midwife and a childbirth educator. Today, she has woven that rich experience into the fabric of her life, as a wife, a mother, a grandmother, a friend, a coworker, an activist and a visionary.

I had the delight of seeing you this past summer walking through a local farmers’ market hand-in-hand with your grandson — you appeared to be beaming in that moment. I recalled it when I read a line in the book where you said, “Thursdays are my Sundays in the church of grandparenting.” It’s a rich portrayal of quite a Technicolor Dream Coat life. And I’m thrilled that we get to chat today and to dive into some of it!

Elizabeth: Thanks. I’m happy to be with you, Kristen. You’re just such a light.

Kristen: Well, thank you and back to you on that. Let’s start at the place where it all began, with KaLiMaJo.

Elizabeth: Katy, Liz, Maggie, Jo who are the four sisters that I write about in the book. I’m one of four girls.

Kristen: Four sisters, four personalities, four lives converging under one roof. I think that sets the stage for us.

Elizabeth: You talked about me being a grandmother — I’m now getting to watch two little boys be brothers because my grandkids live right here in town with me and I get to see them almost every day. It was really interesting writing a book about siblings and then watching them create this — the Cain and Abel story we all know as Westerners, depicting the love and the competition between siblings.

In Western psychology, we’ve put so much emphasis on the effect parents have on us. We do a lot of thinking about how this is because of my mother and that’s because my father. But the role of the sibling is powerful; your sibling is your first real ‘other’. Parents are too formidable to be your other. They’re like the God heads, but the siblings are these powerful beings in our life.

Kristen: We play it all out on our siblings.

Elizabeth: Yes, from the very beginning.

Kristen: You have a great quote about siblings. “If you have siblings they will be your first teachers in this arena. They will serve you a confusing cocktail of care and competition, friendship and rejection, please forgive them for mistaking you as an invader.”

Elizabeth: I’m not leaving out single kids, who don’t have siblings, because often you have that with your first friend. But there’s something about, as you said, living under the same roof with these ‘invaders’.

Kristen: Right.

Elizabeth: That is comparable to every story in the world. Look at our country right now where we are all living under the same roof of America. We are each other’s brothers and sisters, but we’re busy competing, rejecting, hating.

Kristen: Invading.

Elizabeth: In my own self-examination I have traced a lot of my capacity to both love and not love back to my early sibling relationships.

Kristen: This book is chock full of metaphors that relate to those experiences and healing. That’s why the word ‘healing’ came up to me, especially in this political climate, particularly in the world that we’re living in.

You had said that you wanted to write a book about the soul self, the authentic self, the true self — to explore why we forget who we are and how we can remember.

Everything started with a phone call informing you that you were the ‘perfect match’ to be your sister’s bone marrow donor. You spoke of how people started to tell you how brave you were.

I love this quote in the book where you said, “People have said I was brave to undergo the bone marrow extraction. But I don’t really think so. You have to be a miserable, crappy person to refuse the opportunity to save your sibling. But getting emotionally naked with my sister… THIS felt risky. To dig deep and to never express grievances, secret shame behind-the-back stories, blame and judgment wasn’t something we had ever done before.” And thus your journey began.

Elizabeth: This is what we came to call our ‘soul marrow transplant’. We did the bone marrow transplant, which is a pretty gruesome experience. I don’t want to make light of it, especially for my sister, and to some extent for the donor. It’s an uncomfortable, painful, long experience. I was the perfect match for my sister.

Kristen: Were you all tested?

Elizabeth: Yes. Siblings have the best chance to match, but there’s still only a 25% chance. The closer to all ten markers matching up the better the chance of it working — and all ten of ours did. It’s literally called the ‘perfect match.’ That was surprising to everyone in the family because my sister Maggie and I are not similar people. It also was a chance for the siblings to do what siblings often do, “Really, you’re the perfect match?” [sarcastically]

I did a lot of research into what that really meant and what might happen before, during and after the transplant. Should she even survive the transplant — and many people don’t because of the amount of chemotherapy you need — she still had several risks to face. One was that her body could reject my new cells. The other is that my cells could get into her body and say, “Hey, this isn’t where we live” and they could in turn attack her. That’s called ‘rejection and attack’ in the medical language. I thought, Wow. That sounds familiar, rejection and attack. Besides loving each other, rejecting and attacking each other is something she and I had done throughout our lives.

Because of my background in holistic medicine and the mind-body connection, I thought if we worked on our relationship we could model something other than rejection and attack and then help each other on a mind-body level. I proposed this to my sister who had a tendency to think everything I did was what she called ‘woo-woo voodoo’. She loved the idea because when your life is on the line…

Kristen: …You’ll try anything.

Elizabeth: Absolutely. We found a therapist who bravely helped us. We only did a few sessions with him. We mostly did the work on our own, revisiting moments in our lives where we built up stories about each other and never bothered to check them out.

Kristen: That hit me like a ton of bricks, because even if it’s not with our siblings, we do that in our relationships every day. The truth is that we speculate about things. We make assumptions. We make up these stories and then we hold them as verbatim and we carry them around for the rest of our lives.

Elizabeth: That’s right.

Kristen: I loved the way you described that the two of you were the perfect match when you were so very different in so many ways. You said you were the dissenter, Maggie was the peacemaker. “She was too little and I was too much. We danced this dance through childhood and took different forms at different ages. My bigness scared her, especially when I stood up to my parents, and her smallness aggravated me.”

And yet you both had this tremendous willingness to do this. On the 1st day of your growth stimulation injections you also started your 1st therapy session together. In a sense, you were cracking open both physically and emotionally.

Elizabeth: It was all happening very fast because literally, if she didn’t have the chemo to prepare her for the transplant, she would have died within days. That’s how virulent her lymphoma was. We had to move very quickly with the testing, preparing me, preparing her. So we wanted to do this therapy session that might teach our cells how to behave and accept each other.

Kristen: To love each other.

Elizabeth: Yes, it all had to happen simultaneously. We found a therapist somewhat near to the hospital in New Hampshire. He is a wonderful man. He later said to me, “I didn’t do anything. You sisters were so willing.” But he did do something. He’s like a shaman, actually.

Kristen: Tell us about what you had to go through physically — the process of becoming a bone marrow donor.

Elizabeth: It’s unbelievably phenomenal and fascinating — and miraculous. Right now in your body — in my body and everyone who’s watching or reading this now — this incredible dance of life and death is going on. We have billions of cells in us and at every moment millions of them are dying and being replaced. At the end of this year you won’t have the same body at all. Your skin cells, your hair cells, your heart cells, your liver cells, your brain cells, millions will have died and been replaced.

We actually have many bodies throughout our life that are replaced and what replaces them are stem cells, and stem cells are born in your bone marrow. If you press on your hip you feel that big heavy bone; inside that bone miracles are happening. I know you don’t usually think of your hip as a miracle.

Kristen: We take it for granted.

Elizabeth: Or you hate your body or think is not up to par, but it is a miracle. These stem cells are waiting in the deepest part of your body inside of your bones. They’re waiting for a message, “We need a new brain cell.” Millions of these messages are happening all the time. The stem cell makes its way out of the porous bones into the bloodstream and finds exactly where it needs to go and then turns into a brain cell, a hair cell, whatever your body needs.

For patients who have a blood cancer, the stem cells are not working correctly, so the solution is to wipe out all the bone marrow and replace it with millions of cells from a donor.

Kristen: We should also make note of the fact that you were named the Queen of Stem Cells.

Elizabeth: Yes. They need a certain million cells and it can take up to two or three days…

Kristen: …And you took five hours.

Elizabeth: I did.

Kristen: They try to get 5 million and you produced 11 million.

Elizabeth: Yes.

Kristen: You were even bossy with your stem cells! [laughing]

Elizabeth: It’s true… or prayerful or something… maybe bossy prayerful?

In order to spill extra amounts of stem cells into your bloodstream so they can harvest them, they give you this growth stimulant that makes you produce way more stem cells than you usually do. It’s actually very painful. Your bones ache. You feel like you’re going to explode from the inside out and this goes on for five days. Then you’re hooked up to this apheresis machine that takes blood out of your body and spins off the stem cells. Then they’re collected in this baggy, five million of them (or in my case 11 million) and then they are frozen until the time that the recipient can receive them.

Kristen: I loved when you described how you and Maggie sat together through the harvesting and how the nurses didn’t want you to touch the bag containing the cells. Yet, like two silly sisters, you playfully held it. Then you kissed it and she kissed it — and it became Maggie-Liz.

Elizabeth: We called ourselves Maggie-Liz for the year after. Because of the transplant, literally every blood cell in her body was mine. She had no more of her own blood. It was all created through my stem cells. We were one physically, but also emotionally and spiritually.

Really, for the first time in my life, more than with my children or my husband or my friends, I came to know what ‘we are one’ really means. I had been saying those words for so long and yet I didn’t really know what they meant.

I came to understand that you can be your authentic self and one with another person’s authentic self. It’s a mystery. The more she and I put away our egos and emerged in love together, the more we also felt ourselves. It was quite something.

Kristen: Going back to your therapy with Maggie, I’m sure it was uncomfortable at first.

Elizabeth: It was scary, and I have a lot of experience in therapy and workshops and counseling. I’ve done more self-help work than is probably legal, because of all of my years at Omega. [laughing] There’s something in us humans that is so afraid to be undefended. It’s as if we’ve spent most of our young years building up defense mechanisms. Then it’s really hard to let them go and to just to ‘be’.

Kristen: This probably leads into your ADD, which I think is really the essence. Would you explain that?

Elizabeth: I jokingly say that ADD — which we usually think means attention deficit disorder — for me, when writing this book, it meant ‘authenticity deficit disorder’. We all suffer from it. We’re really afraid to show who we are to each other, not only our weakness, but also our strength and our beauty. We hide from each other. Just looking someone in the eyes can be scary. It’s really very sad.

Kristen: I think sometimes we make it more complicated than it needs to be.

Elizabeth: We do that because we’re fearful just to do the simplest thing. My sister and I discovered that in the necessity of cleaning up our relationship. We didn’t have the luxury of time to stay defended. It turned out to be much simpler to ask her things like, “When I got divorced, why did you reject me in the time I needed you so much? For a while you barely let me in your home, what was that about?” I’d never asked her that in 20 years.

Kristen: It easier to carry it around than…

Elizabeth: …make something up about my own unworthiness, about her meanness. When she talked to me about the reasons that had happened, years of ‘stuff’ just went away. The reality is that it was about her own marriage, her own fear and that if she let me in maybe she’d have to look at her own marriage. I never imagined that.

Kristen: Because we make everything about us.

Elizabeth: Yes.

Kristen: Half the time we’re so worried about what everybody else thinks about us, but they’re focused on their own stuff. It becomes this vicious cycle.

Elizabeth: I don’t want the take-away from this book to be for people to think, Okay good, I’m going to go out and clean it up with everyone. She said it was easy and that we should do it.

In the course of writing this book, I did do a lot of practicing on other people, friends, colleagues, and I realized something I already knew: There are some people in our lives we can try to clean things up with, and I suggest trying with everyone — but you will get rejected by some people who are not ready to go there, don’t want to go there, don’t have the skills to go there, or are too defended. Sometimes it’s because this person doesn’t want to play with you and you can leave it at that.

Kristen: Share with us how you practiced this in little ways, for example, with a co-worker or a friend.

Elizabeth: Let’s say I’d be in a meeting at work and feel that tingly sense of annoyance or wanting to blame someone for the reason some project wasn’t going the way I wanted it to. It’s about feeling that kind of stickiness, that edginess with another person, to sit with it and consider why s/he’s doing that. Further to that — to ask myself where I could be contributing to that.

I want to be able to address this in a way that will not be heard as some massive judgment, but rather as a true invitation to move to the next level of our relationship for the sake of our friendship, for the sake of the work. Dare I say, without sounding too grandiose, for the sake of humanity moving forward. I actually believe humanity moves forward in those small interactions just as powerfully as if you were a representative of the United Nations. Truly, if we’re going to move things, we need to start addressing those edgy things between friends and colleagues.

Kristen: Right here, right in this house, in this office, in this community.

Elizabeth: That’s right. With your husband, with your child…find ways to invite them into loving conflict. We think conflict is something to be avoided, but down the road, avoiding conflict often actually leads to violence, to something that did not ever have to happen.

We saw what false news created in this election cycle. People believing stories that weren’t true. We create false news all the time with each other. Back to that conflict with my colleague, you can say something as simple as, “That meeting the other day — I didn’t feel good about what we were saying to each other. I think we could probably find a way to work better together. Are you interested in going a little deeper with me? You don’t have to say yes. Are you interested?” Most of the time people will be so touched that you took the time and the courage to invite something like that.

Kristen: It opens the door.

Elizabeth: Yes.

Kristen: When someone simply says, “I’m sorry”, suddenly much, if not all, that anger just dissipates. Everything that you’re holding onto just goes away because you’re heard, you’re seen, you’re acknowledged, right?

Elizabeth: Yes. Part of my work at Omega has been the creation of this Women’s Leadership Center because I know we all have the masculine and the feminine within us. A part of the masculine can never say I’m sorry. It’s just something built into the defensiveness in the masculine worldview of don’t give an inch. This is why I’ve been interested in bringing women into the leadership realm to correct, not to undo. There’s something so wonderful about the power of the masculine, yet also the feminine ability to communicate remorse and to take responsibility.

That’s what my sister and I did in the therapy sessions more than anything. It was actually quite shocking. It was, “That’s what you felt? I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean it, but I do understand how you felt that.” All the way back to, “Why wouldn’t you sit next to me on the bus in elementary school” and responding, “Well, I wanted to be cool, to be with my friends. Did that hurt you?” “Yeah, it really did. In fact it wounded me on a deep level.” “I am so sorry. I didn’t know.”

It is so simple, but it goes the distance.

Kristen: We don’t have to wait for crisis to make this happen, to heal these kinds of things in our relationships. I was so touched by the prayers that each of you said going into the harvesting and into the actual physical transplant. The energetic love that you were putting into making this a success.

The therapist prompted you with one question: “What do you want to tell yourselves as you go into this harvest process?” You said, “May my cells flow like maple sap on a warm spring morning, may they give you sweet life, Maggie. May they keep you with us for many years to come.” Maggie said, “I don’t do prayers, it’s more like a wedding vow. The wedding of Maggie-Liz. I vow to make my body the field beyond wrong-doing and right-doing so that your cells know that they are home.”

Elizabeth: It’ll soon be two years since Maggie died, so that really touches me. I think I’m farther along the path of letting her go than I really am, because little things like that memory can just bring it back.

Kristen: You described that Maggie-Liz year as one in which your life shrunk in ways that you couldn’t have imagined. And then, on the other hand, you said it was the most expansive, beautiful year of your life.

Elizabeth: Yes. I learned a lot just from the act of letting go of everything except taking care of her for a long time. I learned what really matters. I learned how our culture is no longer set up for people to do this most important work.

Those of us who are mothers and fathers, we know how unsupportive society can be in helping us to be good parents because we’re all working so hard. It’s really tough to be a good parent and a good caretaker.

I didn’t know it was the end of Maggie’s life. I thought, she thought, and we all hoped that we were just nursing her. For a while it looked that way. The transplant worked. All my cells engrafted in her, she returned to her work and her life and her mate and her children. Then, the cancer came back. It wasn’t that the cells attacked or rejected each other. There’s always this chance that even if one cancer cell remains hiding somewhere, it can duplicate rapidly.

And that little cancer cell was hiding somewhere and started to duplicate. Once you’ve had a transplant, they can’t give you another one. She never would have survived it, so when the cancer came back she only lived for another month.

Kristen: You talked about something called ‘truth aches’ in the book. You said, “Ever since Maggie and I started to air our truth aches, I sense them everywhere.” Could you talk about that?

Elizabeth: Yes. I love this concept that my friend Jeff Brown came up with, the term ‘truth ache’ — not toothache. It’s when you get very quiet and sensitive toward what’s really going on in you beyond your defensiveness. We’re all defensive. I’m defensive, just ask my husband. [laughing] Once you do this work, it doesn’t go away. We’re all defended, but if you can quiet those defensive voices in you, just sit and notice that the world is full of messages for you. They’re there all the time. They want to tell you the truth.

Kristen: The key is listening.

Elizabeth: We don’t want to listen because if you listen, maybe we’d have to do something uncomfortable, so we move really fast, work a lot, eat too much, and drink. These are the things we do so that we don’t have to feel that ache of truths.

But if we can sit quietly, let them bubble up and aren’t afraid to feel the pain and discomfort of what our life is trying to tell us — we can make our lives so much better, so much more radiant and alive. Then we would no longer need the Band-Aids we stick over the truth aches all the time.

Kristen: Really just about getting underneath the pain.

Elizabeth: It’s scary because usually a truth ache will reveal the path toward what would be better, but that path isn’t always easy. Sometimes it’s really hard. My book Broken Open is all about listening to truth aches, because sometimes what wants to be heard is a huge-ass change.

Kristen: I was deeply moved by the passage ‘Strength to Strength’, which derived from advice a friend had given you during the transplant process. “Give from your strength and give to your sister’s strength. Don’t be the big sister helping the little sister. Don’t be the strong one helping the weak one. Don’t be the fortunate one helping the victim. Give from your strength to her strength, strength to strength.”

Elizabeth: Yes. I’ve actually been thinking about that particular one a lot recently; it’s the opposite of stereotyping. Don’t look at that person through your lens whether it’s a sister who’s sick or whether it’s someone who voted for someone that you don’t believe in. Look for that person’s core. Try to relate not to their political belief, their religion, their race, their sibling pecking order — rather find the core. Find the soul of that person. Soul to soul.

Kristen: Right. Even with yourself. Not just the stereotyping of other people, but the stereotyping you do with yourself, the labels that we hold about ourselves.

Elizabeth: That’s beautiful. That’s a nice way of looking at it too. Look for your own strength because you can’t do strength to strength if you haven’t first found your own.

Kristen: As you say, love is the bridge — “When we know and love ourselves down to the marrow of our bones, and when we know our oneness with each other down to the marrow of our souls, then love becomes less of an idea and more of the only sane way to proceed. We are one, we are many, and love is the bridge.”

I also wanted to talk about Maggie’s wonderful artwork — how you all came together to support her in her determination to complete this last gallery show before she died.

Elizabeth: I do believe each one of us comes into this world with something to do. Sometimes it’s to be a seeker, to know one’s self, and the art of being. Sometimes people come in to be a writer or a therapist or a great parent, a farmer, or whatever. Maggie came in to be an artist.

My sister Maggie was a tough Vermonter. She raised and killed her own animals. She lived in the woods. She was a nurse practitioner, she was a farmer, she was a tough character. All the while, more than anything, she wanted to be an artist. She actually had a very successful craft business, but she never really knew she was an artist and a lot of the voices of my parents and having to make a living, amongst other things, kept her from knowing that.

In the year of Maggie-Liz, she allowed that voice of purpose to absolutely take precedence over everything. She didn’t want to do anything except this new kind of art she was playing with. She let everything else fall away and she was going to finish this gallery show that she had been commissioned to do.

When it looked like she was going to die, I don’t know where she got the energy, the strength and the clarity of mind — because half the time she had morphine in her, was really out of it, and was in tremendous pain. Her lungs were filing with fluid, but she would get up and go into her studio and create these huge pieces of artwork.

Kristen: Beautiful.

Elizabeth: Really beautiful. Very different.

Kristen: Which you have printed here in the book and are just gorgeous [holding up inner book jacket].

Elizabeth: Literally, two days before she died, she dragged her tiny little ass, I mean tiny — she was under 100 pounds — and insisted that we bring her to this gallery where her artwork was being hung for a show. She wanted to be involved in the hanging of it. She got herself down there and as soon as she saw that it was hung to her liking, she came home and prepared to die.

Kristen: In the book you have included ‘Field Notes’ — passages at the end of your chapters that were from Maggie’s journal. There’s one in particular that I would love to read, as this pertains to her artwork and to this final season.

“I’ve been tromping through the woods for 25 years foraging for wild plants and spring time ephemerals for my botanical artwork. I’ve stayed close to home in the Vermont woods, stopped along roadsides all over New England and travelled far and wide in the Alaskan forest and tundra. Now, it is fall, not my usual collecting time for wildflowers and green shoots, but I’m dying. I might not have time to wait for spring. Here in the autumn woods in Vermont, my heart leaps at the broken, eaten, rotting golden foliage and the many colored fruits standing straight up or lying on the ground to plant their seed. Life is so rich even as it prepares to die.”

Elizabeth: I feel I never knew how much her soul was an artist. I never really quite knew that struggle in her until I watched it play out in a way that many people never get to do. To say, “Oh my God, this is what I have to complete.”

Wouldn’t it be great if we could know what we wanted to do from the beginning and not let all of the things stand in the way? Of course we need to make a living, of course we need to fulfill our roles as parents or children or whatever it is that we have taken on. But there’s always room for the soul to sing its song and it’s up to us to create more room for that before we don’t have the energy to do it.

That is what she taught me.

Kristen: I also feel this book is just full of so many ‘why waits’. Why wait to clean up our relationships? Why wait to dig for the soul? Why wait to do what we’re meant to be doing?

Elizabeth: Yes. Even if you don’t feel like you actually relate to this idea of having been put here to create something, the proof is in how you feel when you do what you want to do on a very authentic level. It’s the deep yearning to express something in you. Everyone has that.

Kristen: There was one passage that speaks of Maggie’s regret where she said, “There’s only one thing I’m still chewing on, how I wasted so much time in my life not saying what I really meant, twisting myself into knots trying to make everyone happy.”

Elizabeth: Yes. She really thinks that’s what made her sick. She really believed that there were many years where she twisted herself into so many knots that it set the stage for her to be sick. Who knows if that’s so, but that’s what she died believing.

Kristen: Knots create something. They create some kind of chaos in our lives, right? I was so moved by her words to you, to her family, on her deathbed, where she said, “Be lovers, love the earth and love each other, love comes first.”

Elizabeth: It sounds so nice. We all spend a lot of time quoting people we love, like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or Mother Theresa, the people we put up on pedestals. And they all talk about the Golden Rule: Love comes first, treat people as you would want to be treated.

Here’s the thing: We have to put our practice into motion — take it from our screensavers and our yoga classes and bring it forth. This isn’t a Pollyanna theory, and it isn’t always the easiest thing to do.

Love comes first. I took that as my marching orders from my sister and I try. I try, I fail, I try, I fail. But her words are guiding me.

Kristen: I try, I fail, I reset.

Elizabeth: Especially when things get hard, as they currently are in our country. I have been an activist in my life. I’ve worked for a lot of causes and I actually believe right now that love is an activist’s choice because we’re in sort of a tribalized time in the country, us against them. I lived through the ’60s, but in my lifetime, it’s never felt so tribalized. Them, us, they’re bad, we’re good, and they’re saying the same thing.

This entrenched sense of us against them is what leads to genocide. If you’re a history student and you study Cambodia or Rwanda or Germany, you’ll see this is what happens. Demagogues get hold of a polarized populace. This is where we are now and the way to combat it is literally to try to love the other, to lead with love, even if you’re marching to do so. It’s what the great ones tried to do.

Kristen: We don’t have to be on the world stage to enact that change because, like you said, we can do it here in our house, here in our office, here in our community.

If it starts here, it trickles down — and that’s not a kumbaya notion, it’s real.

Elizabeth: Yes, exactly.

Kristen: I’ll digress for a moment — In the book you mentioned there’s a question that no one has ever asked you in an interview and I thought that I would grant you that question: What two people, dead or alive, would you most like to be seated between at a dinner party?

Elizabeth: I could answer that with lots of people, but the chapter you’re talking about in the book is called “Reading Anna Karenina for the third time”.

Kristen: Which is quite impressive in itself.

Elizabeth: I did it because my father always read War and Peace once a year and I thought well, maybe I’ll try to do the same and read Anna Karenina. The first time I read it I couldn’t relate to it. The second time I read it, I was in the middle of getting divorced and I related to poor Anna Karenina, who was this woman having trouble in her marriage but wasn’t allowed to act on it.

The men were busy having all sorts of affairs, but she was supposed to stay married and it bothered her so much that she ended up (spoiler alert) killing herself under a train. In a way, to go back to what you said about my sister and how she said she regretted not saying what she felt, that was her story. She was Anna Karenina. She stayed married for way too long in a very hard marriage.

The third time I read Anna Karenina I kind of related to everybody. I had a bigger view of what Tolstoy, the author, was talking about. So, to answer your question, which two people, dead or alive, would I like to be seated between at a dinner party? I’d like to sit between Leo Tolstoy and Gerda Lerner, who is a fantastic and overlooked feminist writer — one of my favorite quotes of hers is “we have to get rid of the great men in our heads and replace them with ourselves.” I’d like to hear Gerda ask Leo if he would have changed the ending of Anna Karenina if he were to write it today. I’d like to know what he would say, given that now women are replacing the great men in our heads with ourselves. Maybe instead of killing herself, Anna would have spoken her truth and chosen a whole different way of life.

Kristen: You revealed how you were a seeker asking big questions from the time you were very young.

Elizabeth: Yes. I’ve always been a seeker, but I also always had this penchant as a girl to say what I felt in my society of four siblings and one very strong father. He was definitely the king of our kingdom.

Kristen: Which you didn’t understand. There was a passage in the book where you said, I don’t understand in the house of women how he gets to make all the decisions.

Elizabeth: I was born that way. I was always standing up to him, which made the other sisters very uncomfortable, because it made him uncomfortable and angry. I just came into this world with this personality that was like Hey, wait a minute.

Kristen: And then there is the line from Rumi about the field of love.

Elizabeth: Yes, Rumi — the great Persian poet, the mystic, the founder of Sufism — says, “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and right doing, there is a field, I’ll meet you there.” That’s the poem Maggie and I used in our therapy session. We wanted to meet in that field beyond ideas of you did wrong, I did right, I did wrong, you did right.

Kristen: My last question posed to you is in parting: What nugget would you give to the audience to propel them closer to embarking upon their own soul marrow dive — to guide them to that field of love?

Elizabeth: First of all, thank you for asking such dear, beautiful questions and being who you are. Maggie said to me in our last therapy session, when I was beating myself up for something, “You know Liz, you don’t have to be perfect to be my perfect match.” I think we all resist going deep in our selves and with the other because we think we have to somehow reach this level of perfection before we could ever reveal who we truly are to the world.

Actually, that’s not what the world wants to see. When you see people’s perfected image on Facebook or something, how does it make you feel? It makes me feel like I’m such a schlump. I can never have a vacation like that, have a mate like that. I’m just a loser. But when you present your fullness, all your rough edges, all your kooky mess-ups, your bad thoughts — when you reveal that to other people, they’re like, “Ah, another human.”

Kristen: Because we connect in that space, right?

Elizabeth: Right. It’s not that your strength isn’t real, but if that’s all you present, most people aren’t there, they can’t relate. So what Maggie meant was that we’re perfectly matched even though we’re both so raw, so undeveloped in so many ways, but we’re still perfect for each other.

So the thought I would leave you with is to be your perfect/imperfect self — and fly your flag with pride at just being human — just being here today.

Kristen: Has this propelled you to do more of this, to dig deeper with the rest of your family?

Elizabeth: Yes, I definitely have, with two caveats: (1) Through trial and error, I have noted the people who want to go there and those don’t; and (2) Through honing an intuitive read of people and after excessive trying (because I’m excessive), [smiling] I’ve made peace with the fact that you can’t go there with everyone.

Maybe your sister is too wounded. Maybe your colleague is a closet alcoholic who’s so full of lying that he cannot meet you there. The good news is, however, that most people do want to go there.

Kristen: We all have unavoidable interactions with certain people — then what?

Elizabeth: You ‘be’. To use the hackneyed Gandhi phrase — you be the change you want to see in the world. You be it. You be it with so much integrity and love. You be love. You be love with the most jerky people, and if they don’t want to go there, you’ve tried and the other people around will be inspired by your capacity to do ‘strength to strength’.

With the people in my life who do want to go there, I’ve been blown away by their courage and their capacity to meet me exactly where I am. My older sister and I got the fruits of what Maggie didn’t live long enough to experience. We have cleaned up our relationship to the point where I can’t imagine it better. The same holds true with my friends.

Kristen: Thank you for this love story. Thank you for today and for all the ‘be-ingness’ you have put forth into the world.

Elizabeth: Thank you.

*Editor’s Note:

Maggie died one year after the bone marrow transplant. Her artwork lives as her legacy, testament to what is possible when we become who we were meant to be. For more info on the artwork of Maggie Lake, visit vermontbotanical.com