Infinite Creativity: The story of an apprenticeship turned friendship that taught me a powerful lesson

—

In high school I’d learned how fulfilling it was to make my own opportunities, and I assumed I’d be able to do the same in college. But college didn’t turn out to be all I’d envisioned.

On the side, I got a job moving heavy boxes in an old mansion on Beacon Hill for the publisher Little, Brown and Company. I carried boxes of books from the attic of the mansion down to the lobby. It was the mid-nineties, and the publisher’s art department was transitioning from spray glue to Photoshop. They even had an old Photostat machine in its own little darkroom — a huge and expensive machine that did the same job as a ninety-nine-dollar scanner. I knew my way around a Mac, and designing book jackets looked like fun.

So one day, when the entire art department went out to lunch, I snooped around until I found a transmittal sheet for a book that listed the title, subtitle, author, and a brief summary of what the editorial department wanted for the jacket. The book was Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band, by Scott Freeman. I sat down at one of the workstations and created a book cover for it. On a dark background, I put “Midnight Riders” in tall, green type. Then I found a picture of the band, also very dark, that looked good below the title. When I was done, I printed it out, matted it, and slipped it in with the other cover designs headed to the sales and editorial departments in the New York office for approval. Then I went back to moving boxes.

Two days later, when the art director came back from presenting designs in New York, he asked, “Who designed this cover?” I told him I had. He said, “You? The box kid?”

I explained that I knew computers, and that I was attending college on a scholarship for the arts. He offered me a full-time job as a designer on the spot. The New York office had picked my jacket to use on the book. Looking back, it wasn’t very good, but they chose it.

I was being offered an honest-to-goodness full-time job. Should I take it? College so far had been a disappointment. And here I was being handed an opportunity to work directly with the art director, who would turn out to be a master. The way I saw it, people went to college in order to be qualified to get a job like the one I was being offered. Basically, I was skipping three grades. Besides, I’d learn more here, doing what I wanted to do, than drifting anonymously through college. So I dropped out of college to work at Little, Brown, one of the best decisions of my life.

I’m not advocating dropping out. I could have entered college with more focus in the first place, or I could have tried to change my experience when I got there. But taking a job that I’d won through my initiative was another way of controlling my destiny. This, as I see it, was an example of manufacturing my own opportunities.

This is why starting a lacrosse team, producing a play, launching your own company, or actively building the company you work for is all more creatively fulfilling and potentially lucrative than simply doing what is expected of you.

Believing in yourself, the genius you, means you have confidence in your ideas before they even exist. In order to have a vision for a business, or for your own potential, you must allocate space for that vision. I want to play on a sports team. I didn’t make it on a team. How can I reconcile these truths? I don’t like my job, but I love this one tiny piece of it, so how can I do that instead?

Real opportunities in the world aren’t listed on job boards, and they don’t pop up in your inbox with the subject line: Great Opportunity Could Be Yours. Inventing your dream is the first and biggest step toward making it come true.

Once you realize this simple truth, a whole new world of possibilities opens up in front of you.

On my first official day of work as a designer at Little, Brown, I walked into the art director’s office, and he silently beckoned me over to his desk. Without speaking or turning around, he reached his left hand over his right shoulder and plucked a book from the shelf. Like a Jedi Master, he never took his eyes off me. The book he had selected was a Pantone color swatch book, and it must have been the one he wanted, because he started looking through it. I stood quietly and watched as he slowly flipped through pages and pages of colors. Finally, he stopped in the range of the light browns and tans. He found what he wanted and tore out one of the little perforated swatches. He put it down on his desk, placed one finger on it, and wordlessly slid the chocolate-colored swatch slowly toward me. He then stated drily, “That’s how I take my coffee.”

Oh my God. I dropped out of college for this. I gave up an awesome free-ride scholarship. And now I have to go to Dunkin’ Donuts and ask the lady if she can do the coffee.

In three seconds, all those thoughts went through my head. As I was considering how to replicate that color at the local café with just the right amount of cream, the art director burst into laughter. “I’m kidding! What kind of asshole do you think I am?” And so began my apprenticeship in graphic design and my introduction to a new way of thinking. The art director, Steve Snider, and I worked side by side for over two years.

Book cover design teaches you that for any one project, there are infinite approaches.

There were several factors at play in jacket design. A jacket had to satisfy us, the designers, artistically. It also had to please the author and the editorial department by doing justice to the content. It had to appeal to Sales and Marketing in terms of grabbing attention, and positioning and promoting the book. Sometimes designers were frustrated when their work was turned down by one department or the other. “Idiots. Fools,” they’d mutter, storming around the office. “This is a brilliant design.” And maybe it was. But our colleagues in Sales and Editorial had experience in their jobs, and I learned from Steve to assume that their concerns were legitimate.

Steve told me that once, for a biography of Ralph Lauren, he’d had a brilliant idea. He wanted to put out six different jackets, each in a solid, preppy color with the Polo logo in the upper left in a contrasting color. That would be it. Ralph Lauren’s photo might be on the back. It would have been so iconic. But Editorial nixed it. So that was that. Steve was still proud of the idea, but he understood that his opinion wasn’t the be-all and end-all.

For a book called The Total Package, by Thomas Hine, which deconstructed the world of product packaging, I took a little cardboard box of powdered pudding. I opened it up, ungluing the seams, and flattened it out. I made a jacket that mimicked the deconstructed box, with its registration lines and that little rainbow where they test the ink colors. I was really proud of the final product. But, instead, they used an elegant black-and-white jacket with product shapes on it. My jacket wasn’t used, but the work wasn’t wasted. I put it in my portfolio. I still thought it was cool.

Steve taught me that having a cover turned down wasn’t a problem. It was an opportunity. My job wasn’t only to be an artist, creating work that pleased me. The challenge was to come up with a design that I loved and that Sales and Editorial thought was perfect. That was the true goal.

“Your goals should be bigger than your ego,” Steve used to tell me.

When I satisfied every department, only then would I have really succeeded in nailing a cover.

When Steve and I were stuck, we’d try to inspire ourselves. We’d take a precut matte frame and hold it up against different things around the office. Would the wood grain of a credenza make a good background? How about the blue sky outside? (Steve Snider would later use a blue sky with white clouds as the background for David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest.)

Sometimes there were restrictions that limited our options. We’d be told, “For this book, you have to use this photo. It was taken by the editor’s sister. It’s nonnegotiable.” And the art would suck. I’d say, “Great, gimme that one.” Then I’d turn the art sideways and blow it up eight hundred percent. Now it was cool. There was always another way to go. My creativity wasn’t limited to five designs per book, or any other number. There was always another potential cover. I quickly learned not to care about the hard work that had been wasted. I didn’t take rejection personally. My creativity was limitless. I wanted to come up with another idea. I got a million of these, I thought. I could do this all day long! It was a matter of attitude.

Graphic design is an excellent preparation for any profession because it teaches you that for any one problem, there are infinite potential solutions.

Too often we hesitate to stray from our first idea, or from what we already know. But the solution isn’t necessarily what is in front of us, or what has worked in the past. For example, if we cling to fossil fuels as the best and only energy source, we’re doomed. My introduction to design challenged me to take a new approach today, and every day after.

Creativity is a renewable resource. Challenge yourself every day. Be as creative as you like, as often as you want, because you can never run out.

Experience and curiosity drive us to make unexpected, offbeat connections. It is these nonlinear steps that often lead to the greatest work.

Steve became my mentor. He drove me in to work every morning, and we became friends, playing tennis together on weekends. He was more than thirty years older than me, but we were a good match: I didn’t have a dad growing up; he had two daughters, and he’d always wanted a son. Eventually he started bringing me with him to present covers to the New York office. On the way, I’d ask him a million questions, not just about design, but about life. How did you know when to propose to your wife? How much money did you ask for at your first job?

Asking questions is free. Do it!

With Steve’s encouragement and confidence in me, I left Little, Brown to start a freelance business doing book design. It was the late nineties, so it was inevitable that I would soon expand my services to include website design. Every new business then included website design. I could have started a dry- cleaning service, and the sign would have read alterations/website design. When my friends graduated college and decided to form a web company, I was already designing and building websites. We started Xanga, one of the first social blogging networks together. Learning design with Steve set me on the path that led me where I am today.

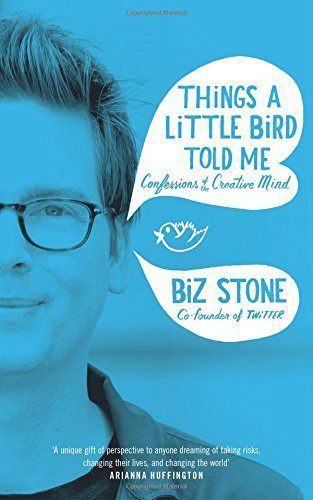

Editor’s note: This article is an excerpt from Biz Stone’s latest book, Things a Little Bird Told Me, which he wrote after leaving the helm at Twitter, the company he co-founded (he has since returned). Recently, Biz expressed his vibrant creativity through his ideation and direction of a short film, Evermore, based on Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven, in collaboration with Ron Howard and Canon’s Project Imagination.

View the film, Evermore, written by Biz Stone and directed by Ron Howard

You may also enjoy reading The Wall | Exploring Urban Media Through Photography, by Steve Snider