How an ex-Buddhist, fierce mama and devout meditator’s seeking to find her spiritual home leads to the ancient devotion of the rosary

—

As a young mother I could not find a spiritual home, this despite the fact that I lived in a town with five Christian churches, a synagogue, any number of yoga studios, a Greek Orthodox monastery, a Tibetan Monastery, and a Zen Monastery. The problem was that on the weekends, after juggling child-care and work all week, I wanted to actually spend more time with my kids and in most religious settings having little kids around was a real problem.

I was a Zen student when my children were born and I had the fantasy, encouraged by the Zen master, that somehow, I could integrate motherhood and meditation. I was given permission to nurse in the zendo. I am a strong meditator and I wore a snuggly so I could slip my nipple into my baby’s mouth with one deft motion while still keeping my back ramrod straight.

In many ways the bliss of nursing was what we were all searching for in the zendo, wasn’t it? The real oneness, the shared exhale, the true letting go.

Birds sang, the wind blew, and all was right with the world. My baby sighed and cooed—and a stern bald-headed nun shrieked across the zendo, “Silence!” After the meditation session she marched up to me. “This isn’t going to work. We can’t have this much noise in the zendo. It distracts the other students from their practice.”

I nodded obediently as I had been trained, but inwardly I had a revelation, “Would you silence the birds, the wind, life itself, if you could attain this unattainable thing you’ve vowed to attain?”

Motherhood changed me. My kids cracked me open. I realized that it was easy to sit still all day comparted with playing with a tired toddler or easing their fears or getting them to eat something healthy or helping them fall asleep after a hard day. I joked sometimes that it was one thing to seal yourself off in a cave for seventeen years to attain enlightenment and another entirely to raise a child during that time. Still, I yearned for spiritual companionship. I craved deep hard talks about my real concerns—from how to protect my kids from the berserk over-scheduling of modern life to worrying about the state of the planet and what it meant to all our children.

My own mother had died when my children were very little and my mother-in-law lived thousands of miles away. Like so many other young people, I had a network of friends my age but no extended family living close enough to offer daily wisdom and support. I yearned for a group of men and women who might explore the spiritual teachings of parenting together.

What does it mean to mother our children? What does it mean to mother each other? What does it mean to mother the world?

For a little while we went to the Episcopal church down the road. But the kids were all marched out at the beginning of the service into a small back room so the grown-ups could get down to the serious business of hymns and homilies. Ex-Buddhist that I was, I ended up teaching Sunday School, taking care of my kids… and everyone else’s, too.

In truth, I preferred to be with the kids who sat in a circle, babbled about what was really going on in their lives and asked endless questions. I began to imagine a group that was less interested in matters of dharma or dogma and more about, what I now called to myself, “sacred chit-chat.”

We would meet and pray and talk, not about heady theological matters but the gritty tough stuff of everyday life.

In such a group, children would feel not only included but able to participate. Spiritual insights emerged from the mouths of everyone around us in our lives not just the robed masters and collared priests. Why was their spirituality privileged over the wisdom of old women who had raised children, kept everyone fed and clothed, and washed and buried the dead? We stopped going to the Episcopal church one day when, on our way to services, our daughter sighed in the back of the car, “Oh man, I hate Jesus.”

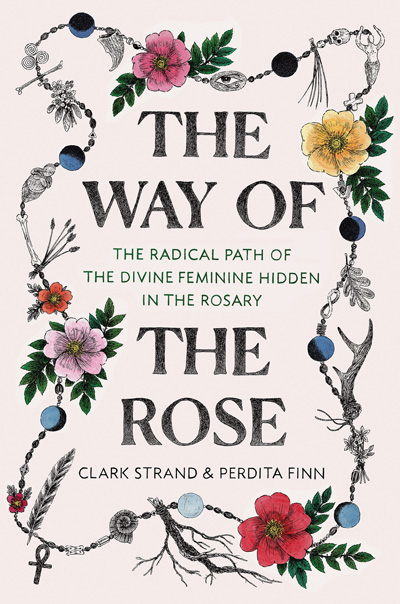

We settled into the rhythms of our own home. Some years earlier, for reasons it would take me a long time to understand, I started to pray the rosary. I hadn’t been raised Catholic, although my Irish ancestors certainly had been, and I didn’t know any other ex-Buddhists who found muttering the words of the Hail Mary mysteriously comforting. I usually prayed the rosary at night in bed with the kids. They’d play with my hair as I fingered my circle of beads and we’d all drift off to sleep together feeling soothed and held. “Pray for us now and at the hour of our death.”

I was embarrassed to tell anyone what I was doing. Compared to zazen or centering prayer, the rosary seemed like such an old-fashioned old lady thing to be doing. I mean, I was pro-choice, an avowed feminist, and well aware of Christianity’s history of violence. But I loved my rosary beads.

Only many years later would I discover how old rosary beads actually are, that they are found in every religion, and hearken back to ancient devotions in which rose garlands would be woven with prayers for the Great Mother.

I would learn too that while meditation probably emerged from the hunting behaviors of early peoples, bead practices, on the other hand, seem to have evolved from the gathering behaviors of women as they collected seeds and nuts and berries. If the hunter is quiet and focused, the gatherer is a multitasker — chatting, muttering, moving about, and communing with others. Legions of grandmothers have wrapped their rosaries around their wrists, sneaking in a prayer or two between the dishes and the laundry. Children can be tended, old people cared for, the carrots chopped for dinner, all while staying in conversation with the Lady.

I began to explore the mysteries of the rosary, fifteen episodes from the life of the Virgin Mary, that one could visualize or explore while saying the prayers. Two pregnant women talk about how their children are going to change the world. A woman’s delivery does not go as planned and she ends up giving birth in a stable but it’s all okay and angels come. A mother loses her child and cannot find him for three days. I began to have the conversation with another mother that I had been longing to have, only this Mother was the Mother of All Life.

And then of course when I was no longer looking for it, the community I had been searching for my whole adult life finally materialized.

My husband Clark was also a spiritual seeker increasingly dissatisfied with hierarchical religious communities that privileged the institution over the individual. He had become fascinated by leaderless twelve-step groups that offered healing and fellowship without becoming compromised by endless fundraising campaigns. Through a series of genuinely miraculous events, he decided that we should start a rosary circle together — and people started showing up.

Friends who’d long since abandoned their Catholic upbringing found their grandmother’s old beads. Others who’d been raised Jewish began praying the rosary. Neighbors who were Wiccan or Buddhist began coming too, along with those who were simply struggling and needed help with their families, their finances, or their health. A woman who’d written a popular book on Marian apparitions heard about us and started showing up each week, and the word began to spread.

Some people brought their dogs, others their children. Kids could nurse or play or babble or color and they weren’t in the way, they were the point.

Mothers could bring their worst fears and deepest prayers and together we could hold each other in both sorrow and joy.

We began a group online and soon people from all over the world were joining us praying the rosary in a spirit of openness and inclusion. There are lots of mothers in that group. Mothers struggling with difficult pregnancies and sick children. Mothers who have lost their children tragically and are now fighting for everyone else’s. Men who are seriously interested in exploring what it means to manifest their mothering from within. Mothers tending to the garden of the world in countless ways.

In our family we have prayed the rosary together when friends and pets have passed on. It’s an all-purpose prayer, a mother’s first aid kit, for all the big moments in life from funerals to weddings. I never expected my kids to say the rosary, but they both turned to it when things went belly up as teenagers. Still, it comes and goes from their lives. But I know they will have it when they would need it most — when they became parents themselves.

When I finally found the rosary, I was no longer searching for a spiritual home. I had found that home wherever I was with my own family.

You may also enjoy reading Entrainments of Heart: The Stitch Work of Community by Mark Nepo