How women of war-torn lands — and lipstick — helped a feminist reclaim the beautiful pieces of herself

—

I did not grow up thinking I was beautiful. My Iraqi mother had fed this belief, telling me that my cousin Nadia was much better looking than I was. Whenever she came to visit and we were all invited out somewhere, my mother would insist that I give Nadia my best clothes to wear. At ten years of age, I finally protested. “Why did you give Nadia my orange shirt, Mama? You know it’s my favorite.”

“But honey,” my mother responded. “Nadia is the beautiful one.” It was as if beauty itself was reason enough.

My mother didn’t think of me as ugly, just not as beautiful as other girls.

But the judgment stayed with me. As I grew up, I couldn’t see anything pretty or attractive about me. I could see only my prominent twisted nose and unattractive legs. I took to wearing clothes a size bigger than I needed so that they would hide my imperfections. They ended up hiding all of me.

As I started studying women’s rights in college and took on a feminist identity, I also made a statement out of rejecting fashion and beauty. If women around me wore the latest fashionable colors, I wore only black and gray. If they permed their hair or straightened it, I refused to do anything with mine.

Rejection became part of my identity, and this continued after college.

At important life events, including giving a speech or receiving major awards for my humanitarian work at the White House, I’d wear a simple black and white suit. I wanted to be treated the same as men. I thought that by denying any sense of beauty, I would guarantee that my intellect was noticed, not my looks. I thought this was the higher choice.

But the truth was that whenever I went out with female friends, regardless of their sizes, shapes, and looks, I always felt less beautiful than them. If we entered a restaurant or an event together, I assumed that I was invisible. If we encountered a group of male friends, I never expected any attention from them. I didn’t feel jealous; I just felt small.

Still, I kept pushing against that idea that, as a woman, I needed to be beautiful. I focused on developing my charisma, my personality, my thoughts, and my adventures.

I thought it was better for people to love me for my mind.

If other women seduced with beauty, I tried to seduce with words and intellect. My unique work in war zones gave me my confidence. But a confident person acts out of fullness, not out of scarcity. I used my activist identity to cover up for my insecurity about my looks. I couldn’t appreciate beauty, so I rejected it. That rejection insulted the essence of beauty itself.

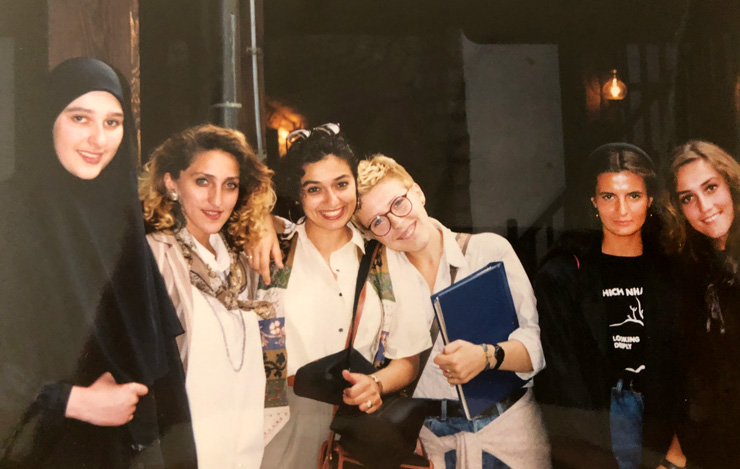

It was the women whom I had been helping in war zones who taught me to see beauty in a different way. I was in Sarajevo in 1994, bringing money and clothes to Bosnian women in the besieged city. Their homes — and streets, schools, churches, hospitals, and way of life — were being destroyed by snipers and artillery fire, and they were blockaded inside the city while food and basic supplies dwindled. The only way to enter Sarajevo was on a United Nations plane, and even the UN could not guarantee anyone’s safety. I was the only woman in a plane full of French UN troops, crossing Serbian check lines to get into the city. At that time, I had heard all about the rape camps and concentration camps in the country. Traveling to Sarajevo was very risky.

With the help of the UN, I made it to the city center without harm, but everywhere the walls were full of shrapnel. People ran from alley to alley to get around, often in a rain of bullets. Everything was scarce — food, water, heat. Many burned their shoes, books, and furniture in the winter for heat. The dead had to be buried in backyards because it was too dangerous to go to cemeteries.

In spite of the danger, I was able to meet with several women’s organizations to distribute the funds I had raised for them. It was exciting to meet and hear about their needs and realities and to think about how to help them better. I asked them what else I could bring besides clothes and money. I had in mind vitamins, tampons, bandages, and other practical items.

“Lipstick!” the first woman said. “We want lipstick.”

“Lipstick? What?” I was taken aback. Why would they want lipstick? They had so many more urgent needs.

“Lipstick is the smallest thing I can put on and feel beautiful,” the woman told me. “I want that sniper to know that he is killing a beautiful woman.”

Resistance comes in different ways. Some fight back with guns. Some fight back by keeping the music playing, like the Bosnian cellist who played in the middle of an open square where snipers could easily shoot him. Some fight back with art, like the artists who turned empty bullet casings into pieces of art. This woman was fighting back by keeping beauty alive. Putting on lipstick was the simplest way to feel beautiful and connected to life itself. It’s how she could triumph over the humiliation of being starved and possibly killed by an unseen gunman.

It suddenly hit me: to deny women their sense of beauty would be to violate their dignity and integrity.

Even if they were suffering shortages of food and water, even if they lacked basic hygiene, even if they were cold and afraid, they had every right to ask for cosmetics. These women were not just desperate victims. They wanted to live and die in dignity and to choose their circumstances.

On my following visits to Bosnia, I brought boxes of lipsticks, as well as blush, eye shadow, and all the other makeup I could collect, along with the basics of money, clothes, and food. I also paid attention to how I carried myself and what I wore. I had thought that being a humanitarian activist meant ignoring any sense of beauty, so normally I had just worn my normal jeans and sneakers and pulled my hair back. Once I realized that beauty is part of keeping our spirits alive, I got myself a nice skirt and a matching shirt and a good haircut as well. I wanted to show respect to the women I was working with. They were carrying themselves so elegantly, in spite of the war, in spite of their fatigue. They were coming to meetings in nicely pressed blouses and skirts, even when everything they had — even life itself — was in peril. I wanted to be as presentable as they were trying to be.

Over the years, I have encountered thousands of women in many war zones who carried themselves with this kind of beauty, integrity and dignity. They would strive for the smallest hint of it even when they were destitute. Behind their head-to-toe burqas, Afghan women wore vibrantly colored clothes — old pieces of silver or patterns of red, orange, and green woven into the belts they had embroidered. Their faces were immaculate — perfect eyebrows, no hair out of place, dark kohl lining their eyes. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, women who had been utterly violated and abused danced fiercely and sang with all their hearts whenever they could. It was their way of keeping their spirits alive.

If these women who had lost everything could celebrate whatever beauty they had by wearing bright red lipstick, putting on nice dresses, smiling big smiles, and dancing with their full hearts, then who was I to reject beauty? Who was I to take myself so seriously and not dance, sing, or join in what had kept so many spirits alive?

Beauty is not to be denied, not in myself and not in any other woman or man. It is to be celebrated, encouraged, and protected. It is like hope.

When all is lost, when material comfort is gone and loved ones are departed, we can hold onto our spirits by cultivating even small gestures of beauty.

Freedom is an inside job. No one can do it for us, and no one can sell it to us. Only when we see ourselves — truly see ourselves — do we see that beauty is all around us. It is on the inward journey that we find the lasting satisfaction we’re looking for. When we align with it, it can be like the butterfly effect. One small change in our lives, like the air displaced by a butterfly’s wing, can have an enormous ripple effect on our entire complex system of interconnected lives. It can change the whole world.

You may also enjoy reading Interview: Regena Thomashauer | The Power of Pleasure & Reclaiming Radiance with Kristen Noel