Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

A treasure trove of letters from the early 1900’s becomes fodder for an author’s book that will inspire today’s women and activists

—

In 1892, when my great-grandmother Mary Davies was 20 years old, she took a trip from Topeka, Kansas, to Pontardulais, the village in Wales where her immigrant father had grown up. In 1976, when I was 21, I traveled from Poughkeepsie, New York, to Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, to teach English and study meditation.

After four months in Britain, Mary returned to the U.S. and found a job in New York City with the publisher Dodd, Mead and Company. After a year and a half in Asia, I moved to Manhattan and worked for Springer Publishing.

You can see why, in my fifties, when I started digging into her travel diary and discovered the many letters she saved, I felt a kinship with Mary.

I often get the spooky feeling she saved these items for me, so I could write about her. Not that she knew her great-granddaughter would be a writer, but I feel her words have been entrusted to me.

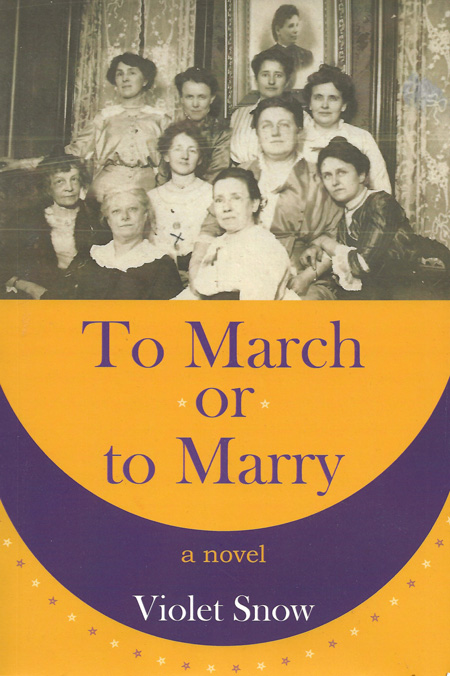

That’s why I am anxious about having used her as the model for a character in To March or to Marry, a historical novel about suffrage and women’s clubs. I believe I have accurately depicted her pluckiness and practicality in the face of such challenges as dealing with her dreamy, romantic husband, who barely made a living as a violin teacher. But in my quest to write about the crises in women’s lives that inspired the early feminist movement, I have introduced events that I am pretty sure did not happen to her.

For instance, it’s unlikely that she met Margaret Sanger, who took on the mission of making birth control available to all women. I shifted the birthdates of Mary’s daughter and twin sons by eight years so Abbie, the character Mary is based on, would be investigating birth control during the period of Sanger’s early activism (1911-1918). I felt justified by a 1932 letter Mary wrote to her daughter, Helen, at the time Helen learned she was unexpectedly pregnant with her second child (my mother). Mary’s comment suggests that her own second pregnancy came a bit earlier than hoped: “You did your best. Only don’t have twins!”

From that brief but feelingful remark, I constructed a plot device revolving around the Comstock Act, which made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious” publications through the mail—including information on birth control. The law was extended to prohibit possession of a condom or a pessary (a device similar to the modern-day diaphragm).

In later years, Sanger took an interest in eugenics, espousing racist attitudes that have made her persona non grata nowadays, but in the nineteen-teens, she was courageous in challenging the Comstock law. Although Mary came from a background so conventional that I don’t believe she was a keen supporter of suffrage, I do think she would have been in favor of birth control. In 1905, when her husband was making enough money to hire an Irish washwoman to help with the arduous task of doing laundry, Mary wrote to her mother, “This will be her tenth child, and so unwelcome! Isn’t it awful? Then I look at our own little baby and think of the care and love we bestow on her, and how other little babies get just enough attention to enable them to live, it seems awful.”

Both for herself and for lower-income women, surely she saw the value of what was then called “family limitation.”

I have no evidence that Mary ever made friends with someone like Louise, the book’s other protagonist, whose attraction to the suffrage movement disrupts her friendship with Abbie. After her parents’ divorce, at the age of fourteen, Mary taught herself typewriting and shorthand and found a satisfying job despite being unable to vote. I’m guessing she didn’t see what the fuss was all about, and Abbie adopts the same attitude. That is, until she realizes men are unlikely to change a law that’s inimical to women’s wellbeing—unless women can vote.

Louise, who is completely fictional, springs out of my extensive research on the suffrage movement. Many suffragists were educated and articulate, and several of them wrote memoirs about the period leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment. I found detailed first-hand accounts of women marching, picketing, getting arrested, and going on hunger strike, so I am confident in my characterization of the bold, quick-tempered Louise and her immersion in suffrage activities. But then I don’t have to worry about her opinion of me.

With Mary, I am on firm ground in regard to her women’s club. In 1904 and 1905, she wrote to her mother almost daily, filling her letters with baby Helen’s antics, household duties, sewing projects, and details of Athenaeum Club meetings. I had never heard of the women’s club movement, although I soon learned it numbered 1.5 million members by 1916. The letters show that Mary’s weekly club meetings were integral to her sense of wellbeing. I believe she would be happy to know I have brought her club back to life, while showing how women’s clubs were a critical, if undervalued, strand of early feminism.

Radical suffragists derided the conservative, largely middle-class clubs, and clubwomen did indeed idealize marriage and motherhood.

It’s understandable that suffs who were out lobbying legislators, speaking on street corners, or serving prison terms, would dismiss the sedate activities of the clubs as unimportant, even pathetic. But a study published during the Second Wave of feminism pointed out the vital role of the clubs. In The Clubwoman as Feminist (Holmes & Meier, 1980), Dr. Karen J. Blair showed how clubs not only changed men’s views of what women were capable of but also trained women in skills that later fitted them for jobs in business and government.

The clubs took the position that a housewife’s values and talents were just what the world needed in the period when the Industrial Revolution was creating professional jobs for middle-class men even as the immigrants who worked in factories and sweatshops were living in poverty. Men were too busy earning a living to devote attention to culture, so one popular type of club engaged women in the appreciation of literature and art by selecting a yearly theme (French culture, for example) and assigning topics to members, who researched and wrote papers to be read aloud at meetings. Other clubs focused on social reform and community service, instigating such projects as citywide trash collection, free kindergarten, the creation of public parks, the establishment of local libraries.

It’s clear from Mary’s letters that the Athenaeum was a literary club. (“Mrs. Flint had a paper on [William Cullen] Bryant, the poet, and then she wanted to discuss a certain poem of his, so she asked someone to read it. No one volunteered, of course, so she asked me. I think I have a reputation for being a good reader in the club.”) The novel’s version of the Athenaeum is similar. However, Mary had been out in the world as a working woman until her marriage to August Wingebach, and documents show she served as club president and as Bronx Borough Director of the New York City Federation of Women’s Clubs. I have portrayed Abbie as the leading edge of her club, nudging the members towards addressing social issues as they become problematic in her own life.

I don’t have Mary’s letters from the period after the birth of the twins, which is perhaps fortunate, since I was free to send Abbie on adventures that advance the action of the novel while revealing the brutal realities of women’s lives. I pray Mary’s forgiveness for stretching her character farther than she went in real life.

I have always admired my great-grandmother. It was such a pleasure to live with her for a year while writing To March or to Marry. Now we continue to keep company as I reach out to share our book with the world.

From Chapter 14 of To March or to Marry:

“Gave in to him at the wrong time of the month, did you?”

The words murmured in Abbie’s ear gave her a shock, not just because of their crudeness but because, over the rumbling of the streetcar wheels and the clop of the horses’ hooves and the chatter of people swaying around her, she recognized the voice. “How dare you!” she whispered through gritted teeth, turning to glare at Louise. “Don’t be vulgar.”

“You shouldn’t have to worry about such things,” Louise replied. “That’s all I mean to say.”

“I have no idea what you mean.” Ivy tried to crawl onto Abbie’s lap, but there wasn’t room alongside her bloomed-out belly. “Ivy, sweetie, sit still in your seat. There’s a good girl.”

“I mean you must have heard of Margaret Sanger.”

“Wasn’t her writing banned for indecency?”

“She’s only trying to give women control over their own bodies. There’s nothing indecent about using a method that stops one from getting pregnant. You might want her help after this one’s born. Or was that your plan, to have two children under the age of two?”

Ivy stood up in her seat and put her plump arms around Abbie’s neck and her candy-sticky fingers in Abbie’s hair. The child’s breath smelled of milk and peppermint. “Here’s a kiss, sweet one, but then you must sit,” said Abbie, her eyes stinging for a moment. Louise’s words had struck a nerve. “What are you doing in town? I thought you were in Washington.”

“I’ve moved back. My mother and I are living in a boarding-house on the Lower East Side, and I’m working as a secretary at the Henry Street Settlement.”

“You’ve learned typewriting?”

“Yes. Alice Paul wrote me a recommendation to Lillian Wald, who runs the settlement house.”

“So you’re quitting suffrage?”

“For now. I have to look after my mother. She’s gone rather dotty these days. I take her to work with me, and she’s all right playing with the children in the nursery.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. It must be difficult.” The streetcar made a turn that flung Louise against Abbie’s shoulder, just as Ivy gave her hair a painful yank. “Sit down, Ivy, and I’ll give you a cracker.”

“Yes, well, I left Mama with the Blakes for almost a year, so I have to make up for it. I don’t mind, really. I like working at the settlement house. I’m learning a lot about the problems of immigrant women. When my mother came over from Ireland forty years ago, there weren’t nearly so many factories and slums, and conditions were quite different.”

Abbie dug in her handbag for a cracker. “But what brings you uptown? Still working on the divorce?”

“Yes, the court won’t grant it without grounds of adultery. My lawyer thought the violence might be taken as grounds, but it didn’t work. Charles is being perfectly horrible, trying to put all the blame on me. Maybe I’ll give up and live in sin with some other fellow. What about you? Are you still an anti?”

“I’ve never been an anti. I just don’t care to sacrifice my dignity by marching in the street when I don’t believe women having the vote will make so much difference in the world.”

“You’re just lucky you married a man who respects your right to make your own decisions. I envy you. Still, once you have a pile of children, you don’t know how Walter will handle it.”

“I don’t intend—ow, Ivy! Now you really must sit, my sweet.”

“You should get hold of Mrs. Sanger’s newspaper, The Woman Rebel. She came by the settlement house a few weeks ago. What a lovely, gentle person, a little slip of a thing, not at all the demon the newspapers make her out to be. But here’s my stop. If you want a copy of The Woman Rebel, write me care of the Henry Street Settlement. Good luck with the new babe.”

And Louise slipped away, leaving Abbie to think over what she had said. Mrs. Sanger was a controversial figure, but if there was a way to stop a third baby from coming on the heels of the second, it might be well worth finding out.

You may also enjoy reading Soul-Voice, by Meggan Watterson