Philip Goldberg writes the human story of the spiritual guru Paramahansa Yogananda

—

As an idealistic, inquisitive student in the 1960s, I made what seemed like a radical shift from Marxist, atheist, anti-religious, political activist to questing seeker, enchanted by the philosophical and spiritual insights of the East. Neglecting my assigned course work, I read everything I could about Yoga, Vedanta, Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and world mysticism, including Western commentators such as Alan Watts and Aldous Huxley, the fiction of Herman Hesse and J. D. Salinger, and the poetry and song lyrics of artists whose lives and work were influenced by those Eastern spiritual traditions. What I learned was not only revelatory, it was practical, empirical, and transformative. I was hardly alone in making that transition; the counterculture was awash in Indian music, fabrics, and ideas, not to mention the music and cultural influence of The Beatles, whose journey to India in 1968 seemed to tilt the planet so the East’s treasures could easily pour into the West. All of which inspired a move away from the drugs that had, for many, opened the doors of perception toward safer and more reliable paths to spiritual experience.

Into my mixed bag of resources came Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi. It was one of the most eagerly borrowed and blatantly ripped-off books in the low-rent districts of strongholds like Berkeley, Cambridge, Madison, Ann Arbor, and the East Village.

I still have the copy I read back then. It’s a hard cover, and the price on the jacket is $5. Since it was unlikely I had five bucks to spare in those hand-to-mouth days, I probably borrowed the book and failed either to return it or pass it along. It was too precious to part with, and it has remained with me through about fifteen moves spanning the continent. The iconic memoir that launched millions of spiritual paths accelerated mine. I was already practicing meditation and yoga postures daily when it landed in my lap like a key piece of evidence for a detective working a case; the self-portrait of a bona fide yogi, the enticing depictions of sacred India, the descriptions of saints, sages, and miracle workers — all convincing proof that what I’d learned, intuited, and contemplated could in fact be true.

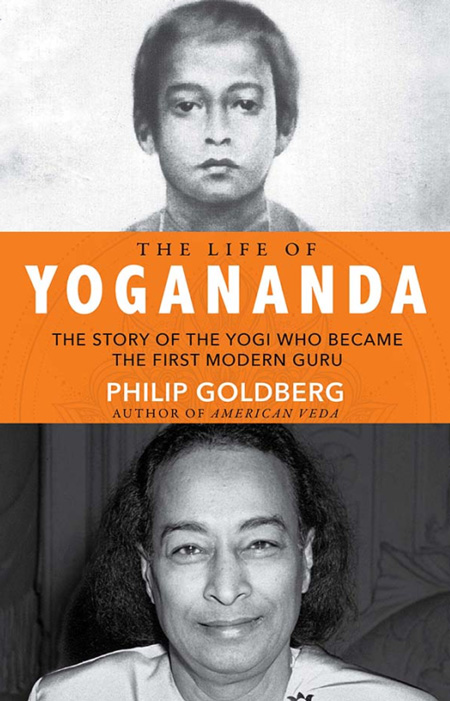

I never became a disciple or a formal student of Yogananda’s, but as my spiritual path deepened and broadened I continued to learn from his writings. When I took up serious research for my book, American Veda: From Emerson and The Beatles to Yoga and Meditation, How Indian Spirituality Changed the West, Yogananda was one of many prominent gurus whose lives I explored. He stood out for several reasons: 1) he was the first major guru to make America his home and the headquarters of his international organization, 2) he was the best-known and most influential Indian teacher from 1920 to the late 1960s (the Los Angeles Times called him “the 20th century’s first superstar guru”), 3) his immense contribution to the transmission of India’s wisdom to the West has endured long after his death, 4) Autobiography of a Yogi was, by far, the most often-mentioned book in the 300 plus interviews I conducted for American Veda,and 5) his life story was so moving, complex, and compelling I felt frustrated having only one chapter to devote to it.

Out of that experience came the idea to write a bona fide biography. The first response by those in whom I confided was: Why bother when Yogananda’s seminal memoir still sold thousands of copies a year? The answer was: the autobiography is as much about other people as it is about Yogananda, and the story contains huge gaps. Less than 10 percent of the book is about Yogananda’s years in America, where he spent almost all of his adult life, and where he made his impact. Periods of several years are virtually dismissed in one-sentence summaries. Books by direct disciples fill some gaps, but far from all, and they read more like tributes than actual biographies.

My goal was to paint a more complete picture of Yogananda than was available elsewhere, and to place his personal narrative in a historical context.

After all, his life spanned nearly six decades of massive social change, lived out in two hemispheres and two vastly different cultures. His teaching years in the West traversed the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, World War II, the dawn of the Atomic Age, and the postwar boom.

I chose to emphasize Yogananda’s human story rather than his teachings, which can readily be accessed firsthand. Even if you believe he was a saint or a divine incarnation, as many of his disciples do, he was nevertheless human — exceptional in numerous ways, extraordinary in many, driven by a unique mission, but still human, with all the paradoxes and complexities that term implies. He had quirks, idiosyncrasies, and peculiarities shaped by a specific family in a specific culture at a specific time in history. He was traditional in many ways and independent and unconventional in others.

He shouldered tremendous burdens as the head of a spiritual organization. He endured managerial distress and continuous financial pressure. On many occasions, he expressed a yearning to renounce it all and return to India and the simple life of a Himalayan ascetic. But he stuck it out, wrestling with tough decisions, beset by strong emotions, celebrating victories and suffering defeats, enjoying worldly pleasures and struggling with sorrow. He was party to controversial lawsuits played out in lurid headlines and salacious allegations. He learned important lessons; he grew as a man; he evolved as a soul — always fulfilling his worldly duties with his eyes fixed on the prize of Self-Realization.

People on the spiritual path tend to romanticize, idealize, and glorify revered teachers, sometimes to the point of deifying them as perfect incarnations of God.

Many labor under the impression that awakened masters are immune from disappointment, anger, and interpersonal conflicts. Not only is this a misconception, it is a disservice to the humanness of those exceptional individuals. On one level, their consciousness may indeed be stationed in the Transcendent, beyond the slings and arrows of what we call the human condition. But on the level of individuality, where a distinct personality inhabits a specific body, they are subject to the karmic laws of cause and effect and they encounter the ups and downs of the material realm. The Big Self is eternal and absolute; the small self gets sick, enjoys pleasure, endures pain, and dies. I knew going in that the status of a great soul was beyond my capacity to describe, but I could narrate the tale of the human being who was born Mukunda Lal Ghosh in 1893 and died Paramahansa Yogananda in 1952.

After I completed the biography, I realized how much wisdom and inspiration I had gleaned in the process of writing it. Yogananda’s story offers useful takeaways for everyone. Even though he was a renunciate monk, he was so deeply committed to his earthly mission that his discipline and perseverance would be the envy of most entrepreneurs. As productive as he was, however, he never lost sight of his number one priority: achieving and maintaining union with the Divine. He taught his students to balance the spiritual and the material, but urged them to place the spiritual first and perform their spiritual practices daily, without fail. He modeled that ideal, and he also modeled spiritual engagement over detachment. He spoke out on behalf of Mahatma Gandhi and India’s freedom struggle, denounced the greed and materialism that led to the Great Depression, raged against militarism and war, bigotry and racism. He was a monk in the world, offering the insights of ancient sages to people with jobs and families, and he walked his talk with dignity, integrity, and courage. Anyone who reads his life story carefully will find him a spiritual role model for the ages.

Learn more about Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi.

You may also enjoy reading Jazz & Spirituality | The Mindful Music of Jack DeJohnette by Peter Occhiogrosso