Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

An accomplished designer steps into his true passion, creating multi-layered artworks with bold color and carefully nuanced composition

—

I’ve known Steve Snider for years…decades, actually. As a photographer, I’ve collaborated with Steve on countless book cover projects during his tenures as Art Director at Little, Brown & Co. in Boston and St. Martin’s Press in NYC.

In his designs, he was always keenly aware of composition, cropping and nuanced texture to distill the emotional content of a book down to a single visual story. So I wasn’t surprised to see him bring these qualities to his street photography of urban walls and surfaces (which Best Self Magazine profiled a few years back in an article titled The Wall). What did surprise me was how lit up, even giddy, he would get while shooting, sharing and discussing this body of work…it has become his life’s work in this next chapter for him.

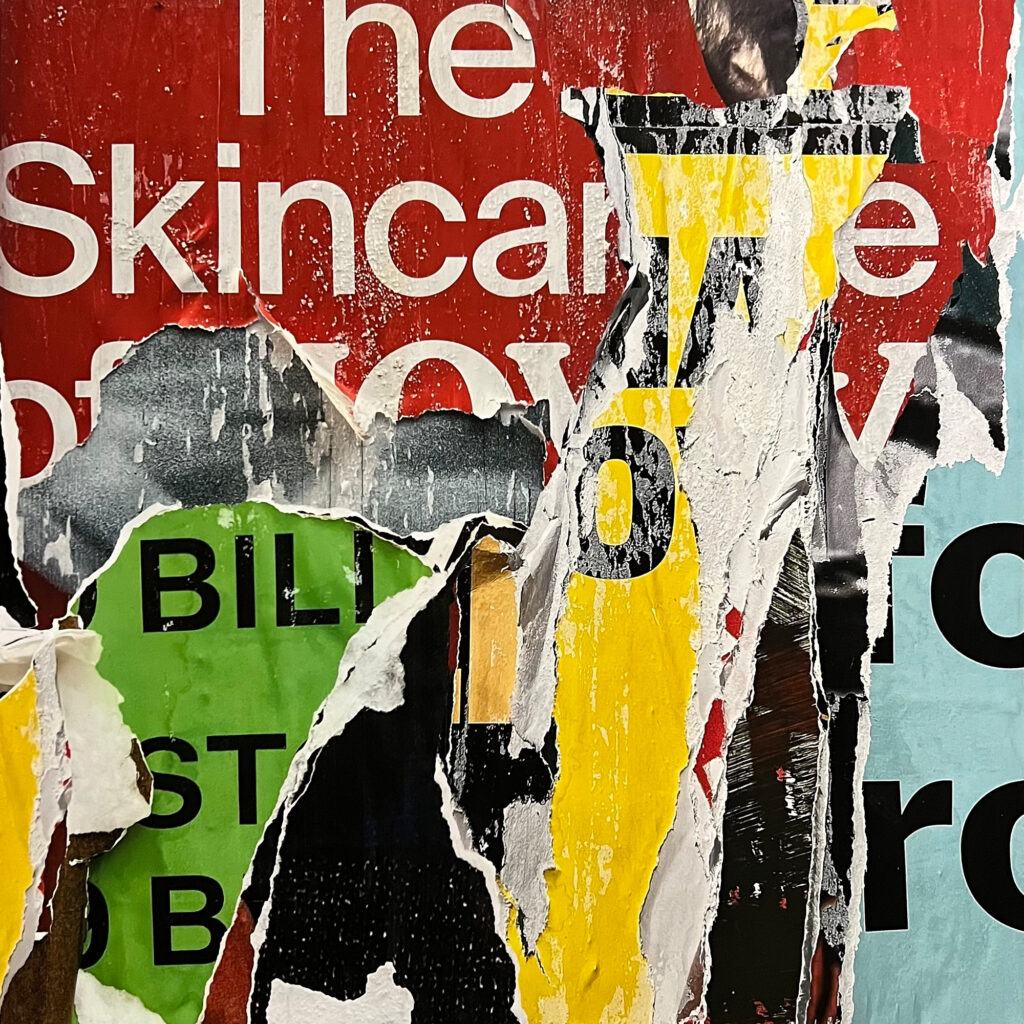

Recently, Steve has embarked on an exciting evolution, now ripping, layering and collaging his photographs into larger, even more textured pieces. In this Q&A with us, Steve dives into his process and inspiration for this next generation of derivative wall art. Be sure to check out the Gallery at the end!

—Bill Miles, Co-Founder and Creative Director, Best Self Magazine

Q: You’ve been creating photographic art from ‘wall art’ — urban walls and surfaces layered with tattered posters, paint, signage, graffiti and the like — for many years now. Tell us about the evolution to this new derivative medium… What inspired you? What is your process?

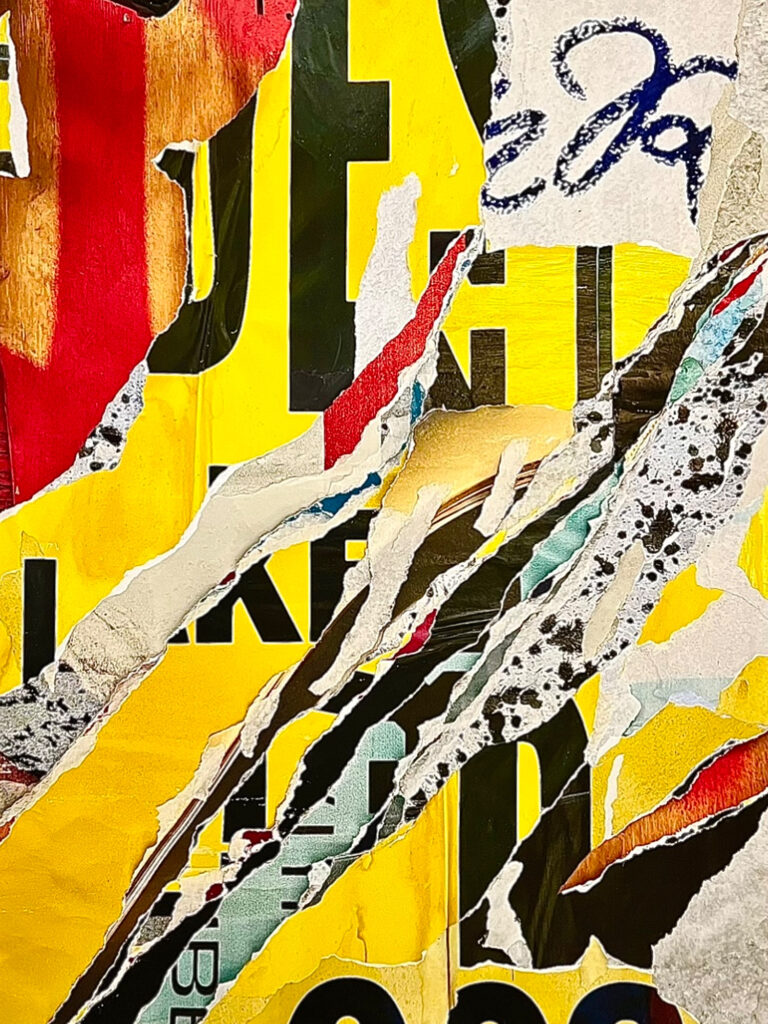

A: Wabi-sabi is the quintessential Japanese aesthetic that values the beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. This echos my response to the torn and weathered billboards indigenous to cities around the world. I began photographing urban walls many years ago, mostly while traveling, when I would have my camera with me. But at home I found the camera too cumbersome to carry all the time, so despite seeing many walls that I wanted to photograph I rarely returned to shoot them. And then something miraculous happened: the iPhone. Suddenly this little device I could carry in my pocket allowed me the freedom to be spontaneous; I could stop anywhere, get as many shots as I wanted and see them instantly!

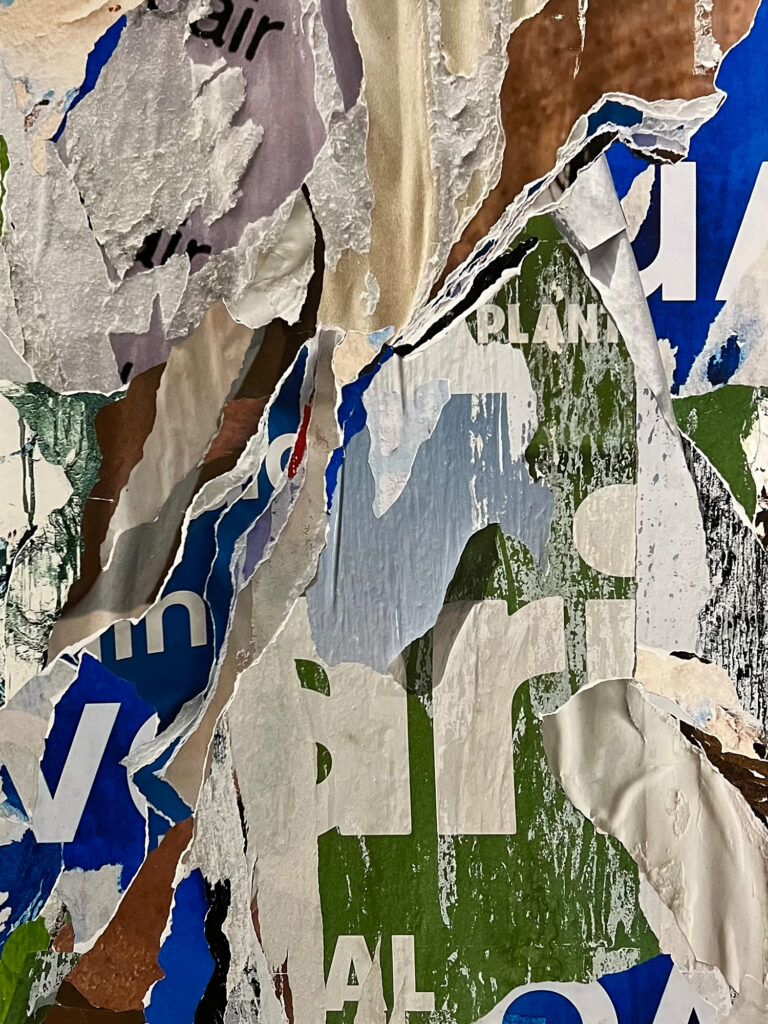

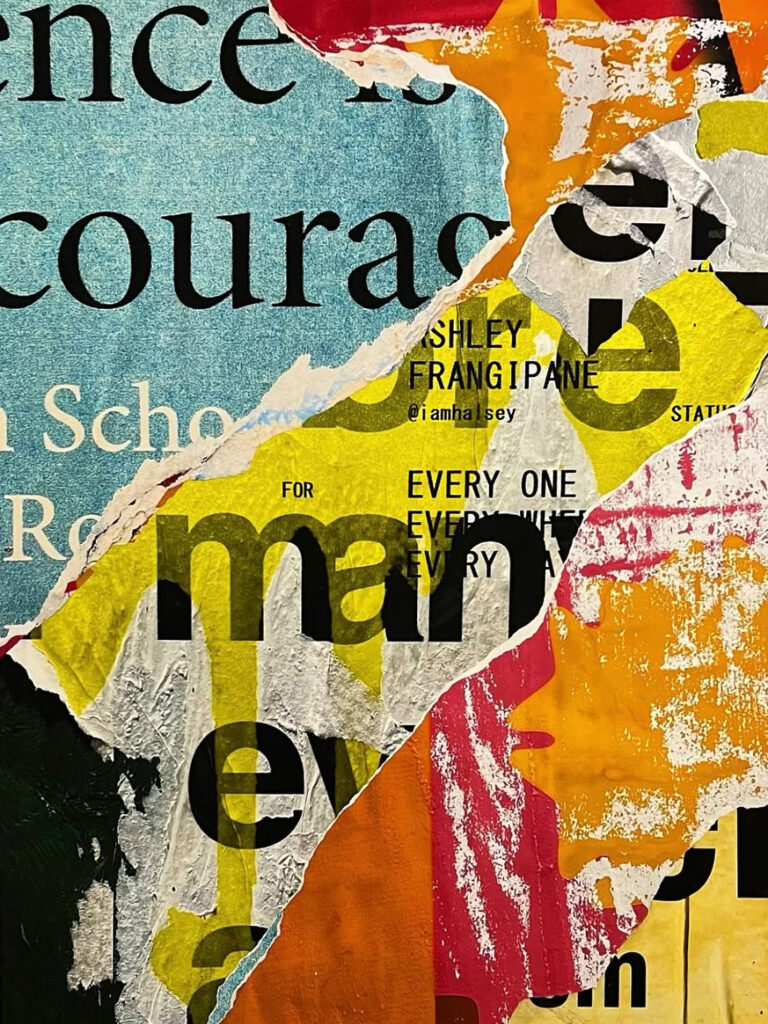

And then a second thing happened: Instagram, a platform for sharing photographs. I began posting images, one a day, at stevesnidernyc and calling them #todayswall. I found myself anticipating time out of the office and anxious to leave my desk at lunchtime to wander around looking for subject matter. Something that had always been within me surfaced as a passion, and I realized that I wanted to devote myself to it full-time. So, in 2014, after 50 years in the publishing industry, my new vocation became seeking out and photographing great walls. I began making prints of my images, 21”x21” squares, but after a few years I felt the need to do bigger work. I began making larger prints of my images and then tearing them and reassembling the pieces into collages that are mostly 36”x48” or 40”x40”. I like to think that using my own photographs separates me from others who work in a similar genre, but who collage with actual material torn from walls.

Q: How do you ‘see’ the compositions and color palettes you craft…is there an intention for social commentary or is it your seasoned designer/artist’s eye the guides you?

A: As a designer I have always viewed the world in terms of graphic compositions. My mind insistently frames what I see. When I photograph urban walls, finding “the composition in the chaos” feels natural to me. Sometimes random bits of images unintentionally interact to tell entire stories. More often, in the collages, the narrative in my work is simply about shapes, colors, textures, patterns, and how they juxtapose. It is not social commentary so much as making a record of our times by capturing this transitory beauty even as it is vanishing.

Q: How do you know when a work is ‘done’? When do you know to stop tinkering and exploring more possibilities?

A: That’s is a great question. I’ve always said that it takes two people to make a great piece of art; one to do the work and the other one to tell him when to stop. But the serious answer is that my own process is organic. I begin with a basic composition in mind but after the initial pieces are glued, I sit with it for day or so before adding or decollaging. At that point I experiment with additional shapes and colors until it feels wholly balanced. I can spend hours on a 4” section. When the rhythm feels right I know I’m done. I love the Trompe L’oil aspect; most of the rips, creases and bubbles are in the photographs but others are real. Various light sources exist within the same space but the eye allows it.

Q: You’ve built a bit of a virtual community in the space of ‘wall artists’ — can you elaborate on how that grew and the surprise relationships and joy that that have unfolded for you?

A: There have been famous artists using torn posters as source material for years; Jaques Villegle in Paris, Mimmo Rotello in Rome, even Walker Evans. I shot my first wall photograph in 1973. Today there are a lot of people on Instagram who photograph walls and many of us follow each other. While at times the images may seem interchangeable, everyone sees with their own eye. I feel what separates my work from most others is the cropping, a skill honed through fifty years of designing book covers. As for working in a genre alongside other like-minded artists, I feel no need for competition. Art movements have never been created by a single artist. I have Instagram friends in many different places around the globe whose work relates to mine. I’ve met up with some when they have come to America or when I have been in their countries.

Q: What is your aspiration as an artist at this point in your life? Is there a ‘big picture’ ambition behind your work or is it purely the pleasure, or calling, of creation?

A: What I am doing now gives new meaning to my days. It makes me feel alive and relevant. I hope that others respond positively to the work, that it provides some surprise and joy. Of course I would love to have gallery shows and sales for validation and recognition, but ultimately it is just for my own expression. When I was designing book covers, I would often get so involved that I felt detached from my surroundings, what I described as being “in the zone.” Similarly, my studio is a world where I can get lost in the work. As I approach 80, that’s a great feeling. As they say: you can’t turn back the clock, but you can wind it up again.

VIEW THE GALLERY: CLICK ANY IMAGE TO ENLARGE

ABOUT: Steve Snider is a graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In his 50-year career, Steve owned his own design studio, served as Art Director of The Atlantic, Design Director of Arnold and Company (now Arnold Worldwide), Art Director of Little, Brown and Company, and Vice President, Creative Director of St. Martin’s Press for 18 years, before turning to photography and his personal art full-time. Steve has designed numerous bestsellers and iconic book jackets and has been the recipient of hundreds of design awards including a Gold Medal from the New York Art Directors’ Club, First Place from the Victoria and Albert Museum, and First Place from the New York Book Show. His work has been featured in AIGA’s 50 Books, 50 Covers, Graphis and Communication Arts, and was included in the show Fame After Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. View more of Steve’s work on Instagram @stevesnidernyc

You may also enjoy reading Francisco de Pajaro | Art Is Trash, by Peter Occhiogrosso