—

Los Angeles is famous for its glamorous, oversized swimming pools, which have been interpreted by decades of artists, ranging from David Hockney to David LaChapelle. But Daniel Wheeler, a transplanted Ohioan who has lived in LA since 1985, took a different approach to the swimming pools of Southern California. Putting on a wet suit and diving into pools with his camera, he took a series of photographs of the visual patterns created by exhaling underwater and aiming his lens at the surface. “I really like the thing that happens right at the surface of the water,” he said of the resulting series, entitled GULP. “There’s light above and there’s light below. There are reflections in both directions.”

That shift of perception — more subversive, and “submersive” than Hockney’s sunny acrylics — is emblematic of Wheeler’s approach to making art in general. His work, which also involves building, sculpting, performing, and fabricating, ranges from installations to handcrafted objects and constructions that include funerary urns and proposal celebrations, chapels, and meditation rooms.

“I’m a bit of a dinosaur because I believe in meaning and communication, story and narrative, and sincerity and a lot of things that people poo-poo,” Wheeler says. “I’m not so hot on irony. So that’s why I don’t really fit in so much in the art world anymore.”

If so, that would be a misperception because the word art itself derives from Latin and French roots relating to practical skill and craft, and that’s what appeals most to Wheeler. “I’ve always been somebody who feels that the real wisdom I have is in my hands and not in my mind,” he says, noting that his earliest experiences with art had to do with building strange objects in his parents’ basement.

The work shown here reveals just a small cross-section of Wheeler’s output, including an early installation piece and a more recent chapel created for an Episcopal school. Each in its way expresses his unique sense of how mindfulness plays a role in art.

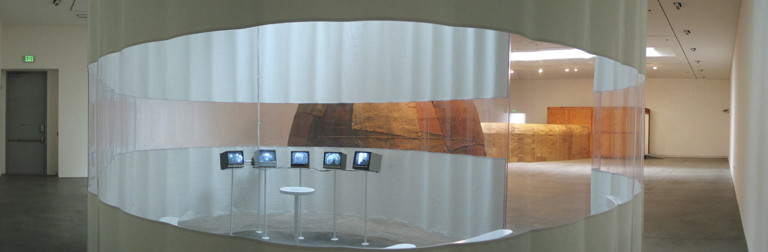

The title of his 2004 installation You Are Here at the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles is a play on the kind of map you might find at a mall or museum, and according to Wheeler is all about what constitutes presence. “You walk into the museum and the first thing you enter is a fully tiled simulacrum of a bathroom with a bathtub, sink, tiled walls, and shower [see image]. But there’s one difference, in that all the holes in the fixtures are re-enameled so there are no exits or entrances. My point in all this was to tweak the psychological relationship to privacy.

“The drains are where all the stuff we don’t want to see — the waste, all the scary things — go down the holes. You feel comfortable at first but there’s an alteration that makes some people very uncomfortable.”

From there you walk through an open shower stall that leads to a long mysterious tunnel that somewhat resembles a mineshaft, ending in the equivalent of a large yurt. Another aspect of the installation is a series of security cameras with monitors that allow visitors to watch what other visitors are doing as they work their way through the complicated space, which also includes a kind of white vinyl tent that looks like a “clean room.” Positioned around the walls are old kitchen appliances from the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. “Your presence triggers some of these appliances to turn on,” Wheeler says. “These were picked because everyone had grown up in a kitchen and had one of those appliances, and it was supposed to jar you into a memory, like Proust’s madeleine.” His reference to the famous sequence in Remembrance of Things Past, in which an “involuntary memory” of Proust’s childhood is triggered by tasting a teacake, adds another nuance to the concept of the installation.

“Meanwhile, other people are in the other space watching you on security monitors. So my question throughout this piece is, Where are you, ever? Are you here? Are you there? Are you in your past? When you’re in your past are you in your body, or are you in both?”

It’s the kind of multilayered conceptual piece that undoubtedly works better when you experience it in the flesh, and have to face all those questions as its creator has intended. [Editor’s note: You can view a digital approximation of the installation on Wheeler’s website, here, but Flash is required on your computer.]

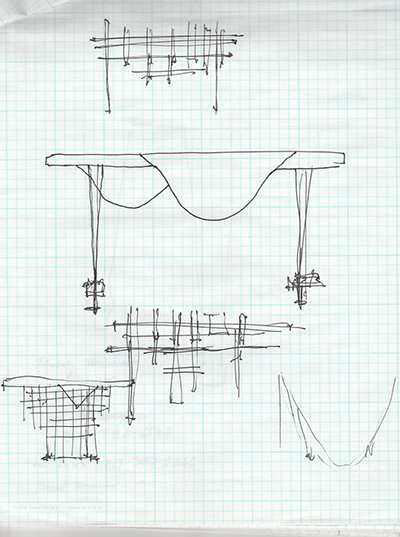

What Wheeler calls these “ontological questions” regarding mindfulness come into play more viscerally in a multi-faith chapel and meditation room he was commissioned to create in 2013 for Campbell Hall, an Episcopal (k-12) school in North Hollywood. “They said to me, ‘We’ve got kids who are overscheduled, overstimulated, working their tails off. We want to carve out a space in the center of campus for the spirit, so that kids can come and find their quiet center — whatever that is.’”

The rough-hewn stone of his chapel interacts with handmade chairs, a deceptively simple altar of polished ash, oak, and eucalyptus, and the natural lighting to create a numinous effect that effectively separates this retreat from its surroundings. Dan was raised in the Episcopal faith in Cleveland, but because his family was involved in education, the faith he participated in “had a lot to do with inquiry, with how we think.” And so, although the setting and tools are different from an installation for an art college, the questions are similar: “How do you get somebody to make a pilgrimage? How do you get them part of the way to where they want to go, and then let them get themselves everywhere else? The notion of pilgrimage and a pathway is central to what I do. I’m interested in putting people on some sort of physical pathway. Movement through space is half the rub of all this. Even if you’re sitting and meditating, there’s a pilgrimage in your mind. My belief is that you go through the body to those places. The goal may sometimes be to supersede the body, but you’re only going through that portal.

The term ‘mindfulness’ implies a less physical thing, but that’s the root of it; it’s the process of finding your way to a harmonious relationship with the body itself.

“The pilgrimage can also be related to what they call in certain religious circles a ‘wander,’ a place where you’re set adrift in the world. The metaphor is that you’re lost in the desert, and that you’re adrift until you’re not. That’s what daydreaming is about. That’s what happens when you’re meditating and you start to wander. That’s a creative moment.”

Wheeler sees a lot of live music of all genres, and whenever somebody ruefully remarks to him that their mind started to wander in the middle of a concert, he replies, “Oh, hallelujah! How great was that! Where’d you go? When that happens to me in the middle of a concert I always think that’s something I was given — a real gift from the musicians.”

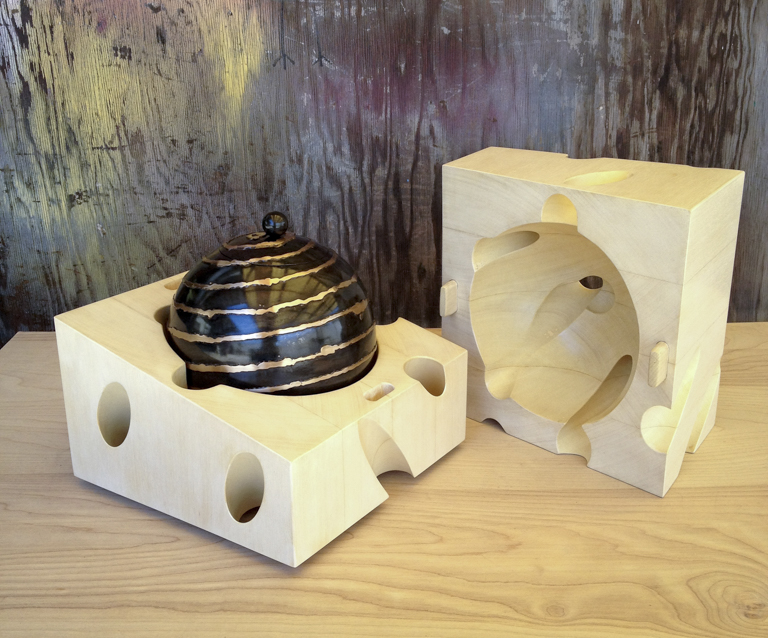

Although he started his career in the realm of installations and conceptual art, Wheeler also has had an abiding love of making solid objects that are not only firmly grounded in the material world but even, some might say, on the fringes of the sentimental. He designs Valentine’s Day gifts, engagement announcements, funerary objects, and grave monuments — the kinds of work that most so-called fine artists probably wouldn’t go near. But because he’s a skilled craftsman and creates the pieces with no overlay of irony, they work in a way that’s stunningly direct and heartfelt.

“Part of that has to do with ritual,” he says of his pleasure in making these pieces. “Valentine’s Day is considered a kind of lowly holiday, but I take it very seriously. I’ve made sculpture Valentines for my wife since we met, and for my two daughters all their lives, so our house is kind of filled with these objects. They’re lighthearted objects, but I don’t take the process of making them lightly.”

Wheeler also considers the value of usefulness, often overlooked in the world of so-called fine art. “I’ve thrown an implied utility back into a lot of my work,” he says. “I like to play with that whole notion of what is the utility of art by implying that you’re going to have to interact with it. One of the reasons I like working in fields of sacred space or funerary objects or love is because there’s not a lot of room for games. There’s no room for it. I can be clever and I can be playful, but I cannot play games. And that makes me happy because I don’t really want to anyway.”

Click an image below to view the gallery:

Visit Daniel Wheeler’s website, Big Objects

You may also enjoy learning about artist Francisco de Pajaro by Peter Occhiogrosso