Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

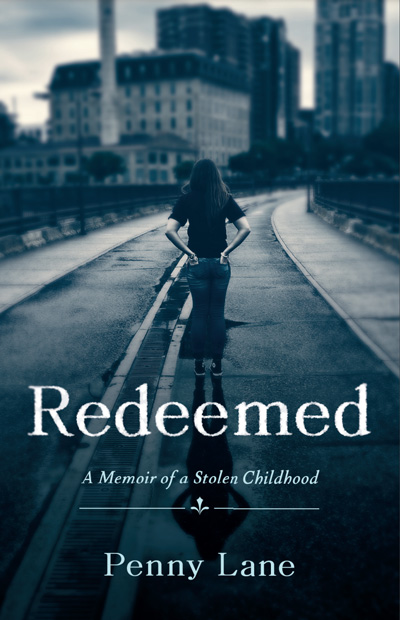

After decades of trauma and conditioning in her youth, one woman finally breaks free to find her way home to her authentic self

—

I grew up in a home where at best I was unwanted, at worst, the scapegoat for the family’s woes. The trauma began early, at age four, after being taken from my loving aunt who raised me when my mother, her sister died of cervical cancer. I was six months old. The stepmother was cold, crippled, and bitter at her misfortune and the man my father turned out to be. She never wanted me, only the son who came later, but took the package to get out of her house. I inherited her housework and childcare as she got sicker, and as my father drank and withdrew more, I got her wrath as well.

Nothing I did was ever good enough. She punished me verbally with terrible names I didn’t even understand, and physically with pots, her nails, the wall, a belt-buckle, and torture — withholding food, blankets, warm clothes in winter, and attacking me in my bed in the dark of night. She hurt me psychologically by telling me I was stupid, useless, good for nothing, when in fact I did everything around the house. She kept me from my birth family, from friends at school and limited my access to her extended family so they wouldn’t know what was going on at home. To make sure I did not overshadow my half-siblings, she limited my access to books, homework time, and college.

I shrunk myself, becoming as small as I could to avoid her wrath, and my father’s attacks to please her. I lived in fear, hiding my face with my hair, never speaking or asking for anything, always hungry, always alert, made fun of in school, unprotected at home, never my own person.

When I couldn’t make it stop, I thought it had to be my fault. If I was only smart enough, I could make it stop, right?

What I did not know when I ran away at sixteen, was that the person I had become under her thumb made me ripe for further abuse and manipulation. I just knew I needed to be away from the constant meanness and the resulting depression and suicidal angst it caused me. I thought my troubles were over, but in reality, they were about to get much worse.

Contrary to what I had been told, I was not a bad kid. A mousy people pleaser, yes, but I still managed decent grades, didn’t smoke, drink or do drugs and was six months from graduating high school a year and a half early. I knew I didn’t want to be a loser like my dad who never had enough money for food or rent, so I kept up with school, got a few jobs, and saved my money, thinking I could buy security.

I started dating my boss at the IHOP, a dashing man six years my senior, a suit-wearing grown-up with a car who swept me off to Little Italy and the Empire State building for dinners, and showed me off to his family and friends. Six years is not much, right? Unless you’re only sixteen. I was too young to see the traps. When I got good at my job, he offered me more hours, and when I accepted, it constantly increased whenever anyone called in sick, him not taking no for an answer. When I complained about my living with a misfit family with a binge-drinking mom, he told me to move in with him and didn’t charge me rent. When we fought, he showed me the door. I was in a box of my own making and because my childhood groomed me to feel so powerless — never having had any choices, I could not see any way out. I stayed.

The worst was still to come. His best friend got “saved” and joined the evangelical church, and soon he started going too. None of us girls at the restaurant believed he could have found religion. He drank, smoked, swore, gambled, and treated people horribly. I went along to church one night, just to see for myself that he was telling the truth, and just like that, they started maneuvering me in. It started slowly at first. Didn’t I want to be unconditionally loved? Of course. Didn’t I want a forever family? Who didn’t? Saved instead of lost? Didn’t I want to belong? Of course…I never had. He converted and soon, under the constant pressure, I did too. We “had” to marry because we were living in sin, and soon, I was shipped off to bible school to cure my “rebellious spirit.”

I couldn’t see then what I see now, that my parents’ grooming me to submit, be to the silent scapegoat, never allowing me to develop as my own person, never having any rights, but creating in me a feeling of fear, insecurity, failure predisposed me jump into whatever offered me a home, family and love.

The Cinderella story has hundreds of versions in as many cultures because it speaks to universal truths and dreams.

We all dream of being free and pretty, wanted and loved, un-oppressed and equal. We dream of being rescued to grandeur and fortune by a charming Prince. Mine is the version where I had to redeem myself from the ashes and cinders, and rebuild the person I never got to become.

The church turned out to be an oppressive cult with an all-powerful leader that no one (but me) seemed to question, and before long I was doing things wrong there too, excommunicated for my troubles and told to speak to no one about it. My husband, domineering, restrictive, chose the pastor over me. I was told to confess to crimes I did not do or leave. Risking hell for the sin of divorce, I jumped ship.

At thirty-one, with no job, degree and little money, I left my husband, home, friends and church to start over again. I had no contact with people who had been my life for thirteen years. I had never lived alone. I moved as far away as I could to California, and slowly, slowly, one baby step at a time, rebuilt my life.

I decided I no longer believed in God, and was sorry I ever did. The new trauma of losing it all and being labeled a sinner uncovered my childhood trauma which I had not been allowed to deal with in the church because it was “God’s will.” I felt unmoored, and cried all the time. I grudgingly went to therapy, afraid to spend the little money I had. But finally, I was validated — told I was the one wronged, that it was never me, never my fault. It was always them, never me…all this time, a lifetime later. They had made it my fault so they could live with themselves.

The sea of life flooded into me. It wasn’t smooth, but it was steady, and it took time. I started dating, and kissed a few frogs along the way. I went to college at night and started a career in finance by day, found love, friendship and life. But the story was far from over.

When my stepmother passed away a year after leaving the church, her son — my stepbrother — eulogized her as a saintly mother, and her family — my stepfamily of aunts, uncles, grandparents and cousins — tried to ignore her part in my life. My stepbrother was the prince and firstborn male in our Eastern European clan, and was kind and accommodating when I was broken and needy, letting me move in with him when I started over. But as soon as I stood on my own by moving out to avoid his moodiness and control, or stood up to him when he disparaged me relentlessly, they pounced. They agreed he was a bully, but I had to make up with him on his terms “because he was my brother.” When I said no, they cut me off. No more calls, Christmas cards, no rsvps for my wedding. I never heard from any of them again, including my brother. It’s been twenty-four years.

I paid a very high price for the privilege of being my own person. I lost my family, marriage, home, my friends, my church, and my faith. But it was nothing compared to what I’ve gained, and the power I felt saying no to my brother. I will never back down again.

—

Writing my memoir was an act of defiance, a validation of my story; refusing to hide, refusing to be ashamed of my past and refusing to accept their white-washed narrative which never addresses my abuse, or their complicity in it. I have lived very well with that. I hope they can too.

You may also enjoy reading Becoming Myself: Making Peace with a Traumatic Childhood, by Roberta Kuriloff.