Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

One woman’s reclamation of grief as a solitary journey

—

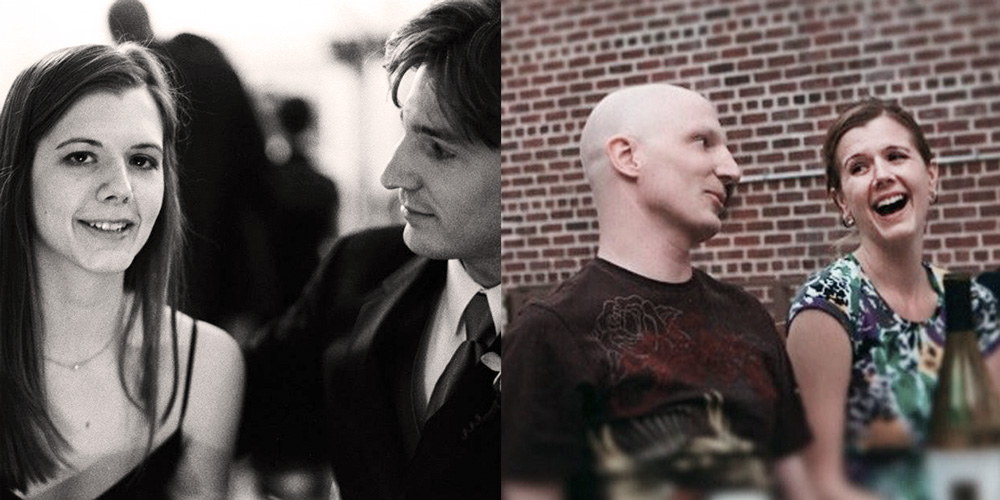

Sitting on the sturdy plastic church chair on the end of one of several rectangular tables, I watched — or, rather, allowed my eyeballs to take in — a slideshow of pictures, most of which were from his childhood. Small Danny, often wearing a tie and frequently photographed with his viola — its neck in his right hand by his side or the instrument positioned under his chin; bow ready in either case to play something magical…to play something most people wouldn’t expect from the limbs of a sturdy-but-skinny young Swedish-German boy from Minnesota.

After ten minutes or so, I noticed none of the photos in the slideshow included me, until…ahh — but there’s one. We were standing in front of his house, I think (or was it the kitchen — stationed in front of a casserole?) when I visited during summer break. I remember the heat and the mosquitos and the leeches in the lake (“There are WAY more than 10,000 lakes in Minnesota”, he explained). I had a brightly colored striped shirt which somehow highlighted my nose ring. I looked uncomfortable as I usually do when I didn’t plan on having my photo taken; as I also usually do when photos are planned.

I’ll always remember (which isn’t quite the same as saying “I’ll never forget”) this day: my late husband Dan’s second memorial service, held on this predictably freezing day in February.

I don’t remember it because of the people who attended, the things that were said, or even that it was the second event — the second memorial held to recognize the thing it took an entire year for me to truly take in: he’s gone. No, not for those things. I don’t recall those clearly — everything was blurry and surreal that year. Twelve years later, many things still are. I recall the impression it made, the tone of the day, the confusion of it all. I’d previously regarded myself as the center of his and our collective universe. And now, here, in his place of birth, I was confronted with the possibility I might be wrong.

Who are they talking about? Who is Danny?

I’d only known (and loved—oh, how I loved) Dan, sans the eeeee sound of “nny”. A stranger for only a split-second as I walked up the steps of our mutual college dorm in Philadelphia, PA, he was only ever Dan to me. We were two kids from the other side of the States who couldn’t have known our choice of university would seal a fate both beautiful and brutal. He was the formal-sounding Daniel only when I was attempting to sound serious. “Daniel Larry Fritz, pick your pants up off the flooooor!” I serious/joked while cleaning our subsequent tiny NYC apartment. “Daniel, I’m so coooold…!” when I needed him to use his radiator-like body to defrost my feet.

I suspect we knew it in an instant on those dorm stairs, too, but after seven years together, we “officially” decided we knew each other sufficiently to make it official. The officiant used both of our full names to marry us in a ceremony our friends and family had waited for — the most inevitable of inevitabilities. Four years later, the cycle of “Until Death Us Do Part” was complete — a reality even the author of that timeless script hadn’t anticipated.

I knew Dan, but who was Danny?

I was angry. I felt betrayed-by-proxy. Who are they talking about? My grief prevented me from seeing anything clearly. Until it was pointed out to me — gently, subtly, and when I was finally able to hear it — that a person’s personal experience with someone is exactly that: personal, I felt like it was a betrayal. I didn’t think the people at the second memorial, his own family, knew Dan.

But they knew Danny.

And I didn’t. I’d missed out on those formative years; the years before the dorm steps; the years before we knew each other — those 18 years when he was, at least sometimes, Danny. Danny belonged to his family and friends from before. Dan, however, was mine.

It was a rocky road from the bitterness I felt at this second memorial to the illogical comfort I now take in this thought (sing it with me): Grief is the loneliest feeling that you’ll ever do….

If you’ve ever lost someone dear — your dad, husband, child, wife, cat; if you’ve ever lost an idea, lost direction, lost your identity…the thought may cross your mind: “No one understands me. No one knows how this feels.”

The popular wisdom is to disagree. “Of course we understand. Of course you’re not alone.” I’m here to tell you I agree — with you, not “them.” No one understands. You’re alone. Alone in your exact experience, alone in your precise feeling of alone.

“They” are only trying to be nice and encouraging — but in my experience, this dismissal of your truth only prolongs the hurt.

Grief feels personal because it is personal.

When I finally both realized and acceptedthis, I felt less alone. And this is another reason why grief is so hard; so isolating: because even if you spoke with your grief twin — one who seemingly walked through the exact same steps on your grief path, she wouldn’t understand. Grief is the loneliest experience, but it also belongs to you. It’s the gift you have left; the peace which surpasses all understanding…

***

I didn’t join the requisite support group when Dan/Danny died. As many times as the social worker on the 12th floor insisted I give it a try, I rejected the suggestion in the same way I’d scoff at a decaf Americano: “Oof! Why bother?!” It wasn’t that decaf (or support groups) or aren’t okay or useful, it’s just that both concepts don’t appeal to me and, I didn’t think would work for me.

Grief may be Universal in that it touches us all, but that universality concept doesn’t address the deeply personal side of grief. There’s nothing about the cadence of the way he said, “Rise and shine, Susie Q! Get in that shaaa-wah!” anyone else can understand. The tilt of his head when he was trying not to contradict me, the squint when it was waaaay past time to leave the party, or the sound of the exhale when he took his last breath and I inhaled my new life.

There is nothing, nothing a group could understand about that.

I hear you arguing — “But people who are grieving get the gist, lady! People understand what you’re going through — at least in general.” I agree. In ‘general’, they do. But grief is specific; grief is all the atoms of a person broken down into fine details and you — only you — have the microscope to see them. Grief is an invisible wave you’re riding that no one else can see. “Look! She’s gliding through the air” they say, when in reality you’re seconds from crashing, mere inches from sinking to the ocean’s floor.

Grief is a bundle of experiences and, yes, things — actual, physical things you don’t wish to share.

In my box of Dan’s physical things is his white undershirt — the one with stains which now smells musty, but used to smell like him. I kept his tiny BlackBerry with the green rubber case — the one I used to look up TV sitcom scripts and read from when he was half awake/half asleep on the 12th floor of Sloan Kettering’s hospital floor. There’s the urn — the big one I once carried onto a plane, whispering to the TSA man, “My husband’s ashes are in there,” while holding my breath he wouldn’t take it out of the bag for inspection. I might have melted into the floor and joined him in the great beyond. There’s his computer case — way too big for my 13-inch laptop — my “MacIntrash” as he first called it back in that dorm room, attempting to impress me with his PC-preferred wit. There are the scraps of paper he wrote on. I’ve scanned and saved and laminated every last bit of physical him.

My grief bundle also contains every word he ever spoke while we slept in late, blankets over our heads to keep warm (and the heating bill low). It includes all our inside jokes from DVD extras and episode 3 of the British Office. My grief is how it felt for him to place his hand on the small of my back when I was mid-panic-attack; his eyes as he pretended to love the mixed-berry fruit crumble I made fresh from the oven, Dan! Just like mom never made! Or the way he didn’t pretend at all when I manufactured a vegan version of his beloved childhood meal of Minnesota Wild Rice soup. It was, objectively, terrible…

My grief is knowing what I knew beyond anything else: he would never leave me (even though he did). It’s walking down aisle 9 of the grocery store and dancing with him to Huey Lewis and the News — spotting the specials in the frozen section while feeling like the luckiest girl in the world. In the frozen section… “It’s hip to eat square!”

My grief is telling him it was okay to let go — so late in the game was I to this thing he needed to hear, but I did it (it was the hardest thing…).

Of course, it was a lie — it would never be okay. But even lies were appropriate when it came to my love for him.

And the truth as you see it, as you experienced it, is also enough. If I’ve realized anything, it’s that the only thing I really have — an object invisible to others — is my experience of him. Of Dan. Of my husband. No one else can claim this. Not his mother, father, sister, brother, best male friend — and certainly no support group. No circle of people grieving for their own Dans, perhaps their Danny. No one else.

***

Let me step back for a paragraph so we can catch our Universal breaths. The truth is grief isn’t always about loss in the death sense. To make it nice and current, this pandemic has caused layer-upon-layer of loss and reasons to grieve, and it also feels personal. One person’s homeschooling conundrum is another person’s decision to let their hair go grey is another person’s aunt who is on a ventilator. “It’s all relative” takes on a topical twist. We gather stories but still don’t/can’t quite understand each other. To break a broken record further, that’s because it’s personal.

***

If you’re still with me, I can feel you waiting for me to change my mind about groups. Maybe you’ve had an incredibly helpful experience in a group. I’m truly happy for you! This is good news!! Maybe you’ve felt held and supported AND understood in your community. It’s oh so good to be in community and share.

But still — your grief, my grief, our Universal, personal grief — it belongs to us together, individually.

These ideas can exist simultaneously.

When I close my eyes and remember him, it’s just the two of us, his hand in mine, using words intended only for me. No one understands what that was like. I cherish that. It belongs to me. It’s personal.

You may also enjoy reading Life After Death: Healing Grief, Redefined, by Sarah Nannen