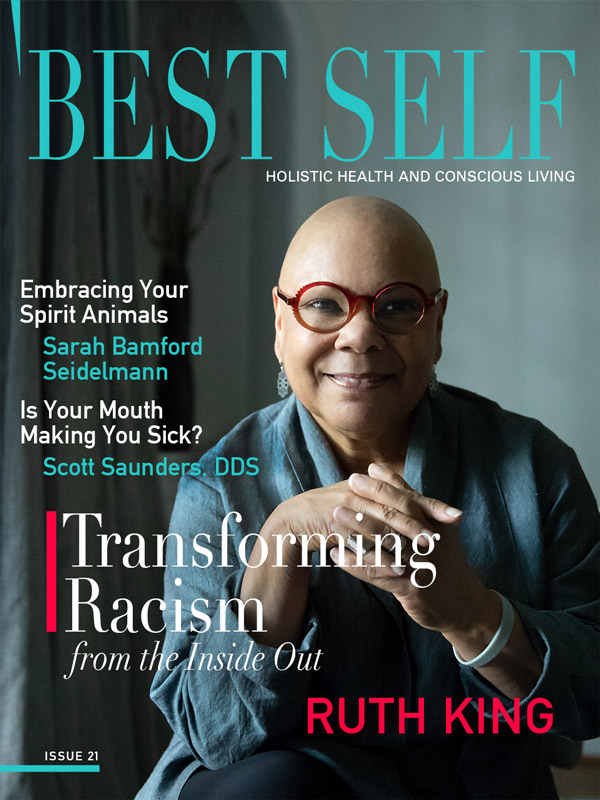

Ruth King

Healing Racism from the Inside Out

Interview by Kristen Noel

June 20, 2018, Charlotte, North Carolina

Photographs by Bill Miles

Racism is a heart disease, and it’s curable.

Ruth King

Kristen: Ruth King is an international insight meditation teacher, life coach, diversity consultant, and author with a master’s in psychology. She previously managed training and organizational development divisions for large corporations, where she also designed diversity awareness programs.

Ruth is referred to as a ‘teacher of teachers’, and the ‘consultant of consultants’. She teaches the ‘Mindful of Race Training’ program, which blends mindfulness meditation principles with an exploration of our racial conditioning, its impact, and our potential.

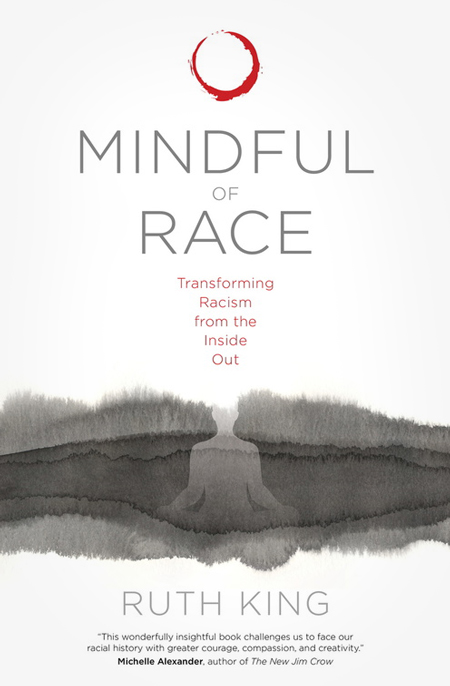

Her latest book, Mindful of Race: Transforming Racism from the Inside Out, has been referred to as healing medicine for the suffering of racism.

Thank you for sitting down with Best Self Magazine today, Ruth, and for inviting us into your lovely home. I knew the moment that your publisher got this book into my hands that I had to explore a way to have this conversation with you. But I also want to acknowledge that this one was a tough one to prepare for because it’s an enormous conversation, a much-needed conversation, but also an uncomfortable one. It was interesting to observe my own feelings that popped up while prepping for today.

Ruth King: Yes. You’re in the zone!

Kristen: I’m in it. We’re in it together.

Ruth King: That’s right. Let’s do it! [joining hands]

Kristen: With regards to our reaction to the word racism, you said, “Something alarming happens when we think or hear the word ‘racism’. Something deep within us is awakened into fear. All of us, regardless of our race and our experience of race, get triggered and more than the moment is at play. That word picks at an existential scab, some level of dis-ease at the mere insinuation of the word, some itch that we can’t seem to scratch, or some fear we believe will harm us. This activation happens to all of us.”

Ruth King: Yes. It’s true. It’s a lot to get our arms around. And yet, it’s necessary.

Kristen: I feel the gravity of attempting to explore this with you — to explore this for myself, to explore this for my son, to explore this for my legacy, to explore this for my community. And I’m tenuous, a bit reserved, to say this or that or to go here or there. It activates a lot of different things.

Ruth King: Yes. One of the things I talk about in the book is discomfort as a core competency for waking up in this area. So, if we’re not uncomfortable, if we’re not feeling some degree of itch or scratch, it’s difficult to wake up. Discomfort gets our attention. The balance of interest in wanting to go there, but also the gravitational pull to not go there is at play — and yet, here we are.

Kristen: One of the things that I appreciate so much about this book is that it’s not just pointing out the obvious. It’s the fact that you’ve provided some tangible, actionable practices that we can do to guide ourselves to relook at something we haven’t known how to approach.

So where do we begin? How do we begin? We undeniably get gripped by this conversation. As you pointed out in the book, we have these default settings or weapons that we resort to when we find ourselves activated. For some that’s fear, for some that’s anger, and for many it’s defensiveness.

Ruth King: We need to begin with the intention to want to begin, again and again — because it’s not like we have this conversation and then and we’re done. It’s a conversation that I think ought to become as normative as eating breakfast.

So, having the intention that you are going to be in this dialog means you’re not going to turn away from it, you’re going to give it some time, you’re going to let it be your teacher for a while, and then you’re going to see how it teaches you how to be more human. A big part of invoking the intention to be in this conversation is to learn from it, to learn about what we don’t know, to question the lies we’ve been told, to decide our scope around how we see humanity.

If you don’t have that intention and you just kind of fall into the conversation, it’s easy to find an exit door. But if you have the intention, and you remind yourself of it — I’m giving this my all, I’m going to be curious instead of critical. I’m going to open my heart to this. I’m going to pause a little bit more, so I can be with what’s happening right here, so that I can learn what I need to learn — I think that’s fundamental. That’s progress.

It’s not the kind of conversation we can casually go into. I often say to others, “If you’re going talk about race to people, make sure you have their consent.” Because, if you start moving into this topic and people haven’t consented to having it, you will waste a lot of energy. Sometimes you have to go there, and you just have to point out some things and let go of the outcome. But if you want to develop a relationship with someone around this issue with the global distress that we’re all living in — if you’re wanting to go there and learn from it, then you need consent. You need a certain understanding with someone before you plunge in and share your opinion.

I don’t want to waste my energy at this stage of my life talking about this unless I have an understanding that we’re trying to do this together. In my activism world it’s a different kind of energy, but in my relational world, I’m very particular about how I am working my energy to make sure it’s purposeful, that it is having impact.

Kristen: And before we go out into the world with it, we need to first have a little conversation with ourselves.

Ruth King: Yes!

Kristen: If defensiveness rises up, we need to get underneath it and ask why? What’s at the core of that? You have two great prompts for people in the book: “Everyone should ask themselves these two questions. One, why are matters of race still a concern across the nation and throughout the world? And two, what does this have to do with me?”

Ruth King: Yes. Exactly.

Kristen: You also say: “This book was not an attempt to resolve the racial injustice that pervades society. No book can do that; rather it offers a framework for understanding racism and our role in it, as well as mindful strategies that reduce mental distress and increase clarity, stability and wellbeing. This, in turn, supports us in responding more wisely to racial injustice, both internally and externally.”

Ruth King: I love the subtitle of the book: Transforming Racism From the Inside Out, because I do think there’s something to be said for how we work with our own activation, our own relationship to how we’ve been conditioned to relate to this topic, the automatic habitual ways that we are in relationship to race and racism, the stories we’ve been told that might need to be questioned — instead of just automatically moving along because it’s something we’re used to. This starts from within.

There’s a contraction that we feel with this topic. Our stomachs get tight. Some people have shared being nauseated, feeling faint, or going numb. And then of course, people can just be outraged and belligerent about it and gather all the proof one can imagine to back that up.

But what’s fundamental to all of that is how we’re gripped inside — and there’s something about working with that grip that’s important — because if we ignore it, then we’re acting out on it. Then our response to this issue gets morphed and distorted and it’s difficult to feel like we’re connecting.

I remember being in an enraged situation not that long ago.

Kristen: That’s kind of hard to believe knowing you.

Ruth King: I got really pissed off and in the midst of it, what I recognized so clearly is how I had vacated the premises. I was not in my body. I felt like I was up in the ethers. I didn’t have any connection with my body or my breath, and when I caught myself and came back, it was quite noticeable. There is a big difference, when you are out of your body versus coming back into your body.

Kristen: So how did you do that?

Ruth King: Well, because I have a mindfulness meditation practice, I’m in the habit of conditioning my mind to be able to come back to the present moment, repeatedly, so it was about catching myself. I’m not blaming myself for the fact that I was righteously in a rage, but it’s essential to witness the impact it was having on me.

I was really hurting inside and what I noticed was that I left because I was feeling so horrible, and these are things we can become more acquainted with and attend to. We need to care for that contraction, that suffering that we’re in during those moments.

When we leave our domain, we leave our power base. We become ungrounded and then our good intention gets defused and doesn’t have the potency it needs to actually make a difference getting the point heard.

Kristen: It’s essentially a life skill to help us navigate through this human experience — no matter what the subject.

Ruth King: In moments when you fly off like that — there’s a need happening. You’re wanting to be taken care, but you’re expecting it to come externally. And it’s very unlikely that whoever you are pissed off at is going to actually come back around and take care of it.

There’s a certain delusion in the thinking, if you’re expecting the care to come from the very person you’re in attack mode with. It’s important that you care for yourself in those moments and not get so far removed from yourself, that you forget that you’re suffering. I often tell people, If you see a hit-and-run driver who’s hit a child and then kept going, what are you going to do? Run after the car or go take care of the child? I think we need to remember to take care of the child, the part of us that’s hurting and needing and suffering.

Kristen: That is a powerful metaphor that’s going to stick with me.

Speaking of metaphors, you take this ugly ‘R’ word, racism, and you give it a beautiful metaphor. You divide the chapters of the book into three parts associated with the heart. Part one is ‘diagnosis’. Part two is ‘heart surgery’. Part three is ‘recovery’. You have this gorgeous line from part one, where you refer to the exploration of diagnosing what is going on: “The following chapters are offered to help us understand the habits of mind that got us here and how we can get the blood circulating again through the heart of humanity.”

Let’s get that blood circulating!

Ruth King: It’s so important that in working with racism as a heart disease, that we take the time to have a clear diagnosis of the problem so that we’re not trying to quickly fix something before we really understand the conditioning — what’s given rise to it.

We need to understand how we got here. There’s a lot offered in part one that supports us in seeing how the patterns of harm have been passed along from generations. It’s not something to feel ashamed about, it’s something to befriend, so that it’s not acting out in other ways. When we’re unconscious about something, it just repeats itself.

And so much has to become more conscious when we’re working with race and racial conditioning, for us to transcend or transform the habits of harm that we’re in. We have to do something fundamentally different than what we’ve been doing, and that requires that we slow down.

Kristen: The truth will set us free.

Ruth King: But it will first piss you off. [laughing]

Kristen: And it may piss off a few other people, too.

Let’s just dive into ‘diagnosis’. One of the elephants in the room, or at least in my room, is this term ‘white privilege’.

You say that the term ‘white privilege’ often turns off white individuals and makes them angry. It’s not a term that I particularly liked, but I also realize it’s a term that I didn’t fully understand — which is the whole point. I had the privilege of not having to grasp that.

Ruth King: Privilege, in and of itself, is a dominant characteristic. So, if we’re looking at racial dynamics, we’re all good individuals, right? And we’re all part of racial group identities. Some of us know that, and some of us don’t.

For example, white people tend to see themselves as good individuals. People of color tend to see themselves as racial group identities. When we start talking about race we bring different understanding to the table. Part of being a dominant racial group in this country is that you don’t see things. You don’t have to.

You just don’t have to look because everything else in society centers around the standard, which in our country, is whiteness. Some would call it white supremacy. Some would call it any number of things, but this kind of collective identity of whiteness is what is dominant in this culture.

It makes sense then, if you’re a member of a dominant race, that you wouldn’t see privilege because to see privilege is to look at a group identity — and many white people don’t associate with being part of a group identity. They associate with being good individuals.

Kristen: That is such a critical distinction. If we can defuse the defensiveness for a second and pause and realize that we’re coming at this conversation from two different vantage points, then perhaps, we can hear each other differently and make some headway.

Ruth King: Yes, because when white people come into the conversation and people of color get upset about something that they’ve said, whites often take it personally from the individual perspective. The conversation shifter comes in recognizing that what people of color bring to the discussion is a group historic perspective.

The dynamic of oppression, dominance, and subordination in our country is real. People of color come to the conversation with an understanding of being subordinated by dominant white culture as a collective, but white individuals don’t see that collective dynamic. They see themselves as just good people, here to listen, but it’s without roots.

Kristen: And they might be good people.

Ruth King: Some of my best friends are very good people, but they lack rootedness — the amnesia of a history, of legacy, of the history in this country — there is no association with that. “I’m just a good individual and that should be enough” — but it’s really not.

Kristen: That distinction helped drive the point home for me. There is a quote you have about white privilege which might help people understand it a bit more: “Whites have the privilege of choosing whether to challenge the status quo. Because of the unacknowledged benefits of not challenging the status quo, many whites choose silence, distance, and safety over the discomfort of change, intimacy, and more honesty. This is how privilege works.”

Ruth King: There’s a collusive nature in privilege. There are characteristics of privilege that get played out collectively. I talk about this as blindness, sameness, and silence. When white people are in a group with each other and something goes down or something is said, but nothing’s acknowledged about what was said even though everybody’s feeling it, but not speaking to it — this is one of the ways that privilege stays in place. People are colluding with an unacknowledged racial group identity.

It’s a very important dynamic to tune into and unpack a bit, because fundamental in those dynamics of collusion, blindness, sameness, silence — there’s fear.

Kristen: Afraid of not knowing what to do?

Ruth King: Afraid of not knowing what to do… and on some level afraid of losing membership in an unclaimed white racial group identity.

Kristen: One thing I really appreciate that you lay out in the book are the common stereotypical narratives of white people and those of people of color. I pulled out three of these from each group. Let’s start with those common narratives that white people use:

“I don’t see color. Aren’t we all the same?”

“Why are people of color so angry with me? I wasn’t living at that time.”

“I don’t know how to have this conversation without feeling blamed, guilty, frustrated, or angry.”

Ruth King: I’ve even heard people say, “Oh, I’m just going to listen. I’m not going to say anything, because I’ll just get nailed again.” There’s this sense of, firstly, not understanding why this is such a big deal and secondly, who needs this? “We could just all get in a room together and hash it out, but there are so many episodes of anger — and I don’t need to go somewhere and be beat up again.”

You see, these are examples of privilege — the opting in, the opting out. This is a common way that we miss each other in conversations.

Kristen: The privilege of being able to retreat to a corner and just say, “Oh, this is too messy. I don’t really want to deal with this. I don’t want to get my hands dirty.”

Ruth King: That’s right.

Kristen: Let’s go back to “I don’t see color.” That’s one way to piss off people of color.

Ruth King: Pretty instantly.

Kristen: And let’s just assume that it’s well-intended.

Ruth King: It is well-intended. And one of the things that I talk about in the book is the difference between intent and impact. It is good intention, but the impact can be white-washing, to say the least.

When you don’t see color, it’s strikes me as not seeing me in the fullness of my experience. To not see color is to assume on some level, whether you know it or not, that we’re all good individuals and we’re all the same. To not see color is what gives birth to All Lives Matter as opposed to Black Lives Matter. It’s not seeing the stars and the constellations.

We can see the single incidence of, let’s say, the immigration issue that’s currently going on — whether children should be removed from their parents or not — and we can look at that as a single isolated event. That’s the ‘stars’; or you can look at the ‘constellation’, where you can look across the globe and see what’s happening to dark bodies collectively.

And you can see the prison industrial complex, and the healthcare industrial complex, and the ways that people of color are impacted by gun violence, whether it’s through force or through their owning of weapons.

When you’re not looking at solo incidents you begin to see the tattoo of the dynamic of dominance and subordination that is pervasive in our society. So, to not see color is to not see the full dimension. It’s coming from a white dominance lens of being an individual and looking at isolated incidents without connecting the dots.

Again, intent and impact. For example, being in a subordinated racial identity group, my life and my people are impacted if I go silent. So, that’s a privilege I don’t get to have.

Kristen: Now we’ll move to some of the narratives of people of color:

“We’re going to talk about race. This means that in addition to being disturbed by white people’s ignorance, I’m going to have to teach white folks what they choose to deny knowing, amnesia of whiteness.”

“I’m angry about race, but if I talk about it, I’m labeled the angry person, and nobody listens.”

“I don’t want to keep educating white people about race. They need to do this for themselves.”

Ruth King: A lot of the themes here from people of color have to do with a cumulative impact, which is what I also talk about in the book. It has to do with a legacy of generational oppression that carries an emotional and psychic weight.

There’s a wear and tear. There’s a chronic fatigue in many people of color from the exhaustion, the invisibility, of having to point these micro-aggressions out so regularly to well-meaning white people.

I think there’s a lot of invisible emotional labor that happens with people of color when it comes to this conversation. And it’s invisible to white people, because at the individual level, they’re not plugged into collective impact.

Kristen: They’re not carrying the legacy of a community.

Ruth King: It’s just something they don’t have to be concerned with.

Kristen: That nuance helps one understand, when observing someone’s anger or someone’s reaction to something, where they are coming from.

You also suggest to not take this journey alone: “While we’re on this exploration. While we’re going to have this conversation with ourselves. While we’re going to look at this and unpack our own feelings around this, we need to bring an ancestor along.”

Can you talk about what that means?

Ruth King: I encourage people, when they are setting their intention, to really look back on their immediate family, to that ancestor who stands out around race. Maybe they were rageful and righteous or maybe they were protective but couldn’t be vocal — or maybe they were afraid but couldn’t speak out because they might be disapproved of. Bring that person along on the journey.

To not see this as just a solo, isolated journey that you’re on, but to dignify their existence and how they had to hold this legacy or this kind of inheritance — I call it a racial inheritance.

We’re all influenced by our lineage, whether we know it or not. You know there are some secrets and stories that are just not spoken, and blatant things that people want to hide. I’m suggesting that in your own heart — you don’t have to tell anybody about this — bring an ancestor along as you clean up your own understanding of racial distress, your contributions and ignorance — someone who might’ve wanted or needed to do that and didn’t have the ability to. You have the privilege to do that now. All of us do.

Kristen: We inherit more than hair color and eye color. We also inherit belief and we bring these constructs along with us throughout life.

We need to ask ourselves, what was spoken about in our houses? What were our parents saying bout racism?

Ruth King: Or not saying.

Many of us carry these stories out of an unconscious loyalty to our parents and ancestors, meaning that we’re behaving this way because we’ve learned that this is the way to behave… and we’ve got to keep it alive because they loved me.

Kristen: …and I owe it to them.

Ruth King: It’s an unconscious dynamic that needs to be interrupted and examined to see if it really is true for you.

Kristen: There’s a term I love — a ‘cycle-breaker’. The cycle-breaker is the healer. You can be the cycle-breaker and you can heal those things that you’ve been lugging around — breaking the pattern.

Ruth King: I actually think it’s our duty. I think when our ancestors and parents passed the baton onto us as children, we took the baton, we ran, we did our best, hopefully elevating the consciousness so that we’re not reliving the same things over and over again. That’s our job, actually.

Kristen: You also state in the book, “What’s unfinished is reborn.”

Ruth King: That’s right. It is.

Kristen: People go off to church on Sunday, but they don’t bring all of that racial angst with them. They don’t bring all of that unrest and that anger and that fear along with them, as if by doing so, pretending it doesn’t exist. And yet that’s exactly where they need to bring it, because that’s where we can heal it. We simply can’t compartmentalize it.

You’re dedicated to using meditation as a tool to help us deal with this. As you said, “Bring your racism to the mat.” Let’s bring that emotion to the mat (and the church or wherever you practice your spirituality), so that we can deal with it.

Ruth King: Part one of the book is really helping you understand how we got here. Part two, which is mindfulness or ‘heart surgery’, is where we bring forth what we’re learning about, how we’ve been conditioned, how we’ve been habituated. What some of us feel is confusion or guilt or shame or rage or disturbance — we’re bringing that to the meditation cushion to compost. The meditation process supports a certain composting of the distress, so that we end up with some rich soil in the end.

The composting process is really our capacity to bear witness to the distress and to befriend it — to investigate the deeper stories, because when we’re silent, we have a chance to hear something much deeper than the habitual mind that’s running around in our heads. We develop a different relationship with our thoughts.

We can be with our thoughts instead of being our thoughts — and that’s a pivotal shift when we’re working with racial distress.

Kristen: I think the reason we’re getting tripped up and triggered here is because we’re simply not ready if we’re not willing to first take that pause, do the self-inquiry, explore our family lineage and our beliefs, and to check in.

We’re ‘loggerheads’, not realizing, I’ve got an individual identity / I’ve got a group identity. It’s just shutting the whole thing down. It’s like chasing our own tail.

Regarding meditation, you write: “The best tool I know to transform our relationship to racial suffering is mindfulness meditation. I was attracted to this practice because my habitual ways of relating to racial distress were not working. I was a righteous rager.”

Ruth King: That’s right. In those moments of distress we’re triggered without realizing it and we’re trying to do something with all that energy we feel. What we do with it is habitual. We’re flipped right into the habit energy without choosing. Mindfulness meditation supports you in not flipping anywhere, instead just kind of softening into the moment.

It’s about befriending this energy. The first mindfulness meditation instruction in the book is about developing a relationship with ease and calm — where we come back to the body and the breath, being aware of the body and the breath, in the present moment. When we flip out in this anxiety and reactivity, we’re leaving the premises.

You can feel the difference between leaving the room when you’re in those moments and returning back to the present moment. This is a practice. This is a healing routine of great hygiene that we can put in the same category as brushing our teeth, combing our hair, taking a bath.

It’s learning to sit and develop a relationship with ease in the present moment without believing your thoughts, without leaving and running. The present situation is often horrible enough; we don’t have to add all these extra layers to it. Can we just be with it?

Nelson Mandela says, “If you can sit in the seat of insanity and dislike without having a need for it to be different, then you are free.” I think that quote really speaks to freedom. He was free way before he was out of prison, because he worked with his mind. He worked with the fact that you can be free regardless of the circumstances that you’re in.

This has been my experience with mindfulness meditation — a sense of increasing moments of freedom that I can have right here and now, regardless.

Kristen: When you get triggered, how does that internal conversation go down for you? What do you take to your mat?

Ruth King: Sometimes I don’t have the luxury of going to a mat. I have to just take a breath wherever I am.

First, there’s a recognizing of what’s happening. “Oh, I’m pissed off. Oh no, he didn’t do that.” There’s a recognition of this upset.

There is an acronym that I use in the book: RAIN (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nurture). Recognize what’s happening. Allow yourself to be with what’s happening. Investigate how you are relating to what’s happening. Nurture the distress. You recognize what’s happening, then you allow it to be there and just say, “Yes, this is crazy. This actually happened.” Because sometimes we flip into “I’m not allowing it,” but instead, we need to flip into, “This is how it is right now in this moment.”

Let me regroup, find the ground beneath my feet, settle into this body, so that I can then investigate what my options are.

Kristen: This meditation is going to take four days. [laughing]

Ruth King: It doesn’t actually take that long once you get it, but first we have to cultivate the calm with the body and the breath before we can really investigate.

We might have a meditation period for a while, where we’re just being with the body and the breath, just easing our self. We need to know that from the inside and once we feel a certain sense of stability, then we can start exploring these different questions: What is this feeling? Is this fear? Is it anxiety? Where did this come from and how old is this?

We need to ask, what am I needing in this moment that can actually be a comfort to me? Right here and now. It has nothing to do with solving the issue out there. It has to do with, how do I love myself, right in this moment?

That’s the internal work that has to be done. That’s what we avoid because we have a false belief that if we do something, anything, that it’s going to help. I’m more concerned about pouncing on activity before you understand the impact that it has and to really take a little time to be more choiceful — to be more discerning about how we use our energy and where we use it, so we’re not burning out.

Kristen: That pause literally calms our entire nervous system.

Ruth King: That’s right.

Kristen: Suddenly we’re open to hear. We’re open to see. We’re open to experience in ways we haven’t previously. If I can just sit for a moment and be quiet, I can observe you in a very different way. And perhaps see where you’re coming from.

Ruth King: And fundamentally, we’re learning that we can give ourselves permission to pause. That we can interrupt our habitual instincts. We can learn how to do that.

Kristen: I also think it is about pushing through that pain a little bit because, as opposed to either flying off the handle or completely retreating, there is something in the middle. And like you say, “The gray area is messy.”

We touched on the individual and racial group identities, but again, it’s not just about whether you’re a white person or you’re a person of color. We have many identity groups, right?

Ruth King: Yes, we do.

Kristen: An example of types of identities include religion, education, marital status, age, physical and mental abilities, talents, gender identity, sexual orientation, economic class, country of birth, race. This also plays into dominant and subordinate groups.

Ruth King: The dominant racial groups can readily identify with all of the other identities except race.

There’s the intersectionality of all of these different racial identities at play. Intersectionality is a term that was mostly referenced to marginalize people. For example, I’m a black woman, lesbian, Buddhist.

Intersectionality speaks to the complexity of all those things together, being played out in the world. It’s not just race, it’s more complicated than that. Most of my identities are subordinated, but I think we can all relate to both subordinated or dominated groups — not so much racial groups.

Kristen: It’s a critical construct. You say, “Dominant and subordinated group dynamics are deep in our psyche and are reflected in the world in which we live. This is our social conditioning, cultivated over many generations. Approved by some, glossed over by others, and gravely impacting most.”

Ruth King: It’s true, this power dynamic is so important to see, but you can’t see the power dynamic of dominance and subordination if you’re just looking at it from an individual lens. The only way to understand it is at group level. It’s the constellation, not the isolated incidents.

Kristen: It’s funny. I said you were shifting the conversation, but I think you’re actually giving people binoculars, to take a closer look, to lean in.

You state, “Racism occurs when dominant group culture, whether knowingly or unknowingly, both now and in the past, imposes its values and beliefs on other races as a social norm and standard. Racism is difficult to comprehend when we look from the individual identity lens. To understand racism is to examine not only the system, policies, and practices that ensure it, but also the forces that resist changing it.”

Ruth King: At the individual level we can all have biases. At the racial group identity level, we can all discriminate; but racism is part of the institution. It’s part of the policies, practices, social norms, the body in our culture that influences standards and what’s in, who’s in, who’s out. That’s where racism lives.

I seldom use the word racist. I use racism to really point to the system and I use the term biases, not that individuals can’t do racist acts, but I think that power happens in collective form. Whether knowingly or unknowingly, consciously or not, it’s really important to see how this plays out.

We can look at the constellation of the two guys who went into Starbucks. That could be a solo incident of seeing that the manager called the police. But when you add that to the five black women who were playing golf, to the black woman that was taking a nap at Yale University and somebody called the police — there are a whole series of incidents that allow us to see the constellation.

It’s as if there is some kind of standard or permission that people feel they have to call the police when they feel threatened individually — without understanding the collective impact of that action; of targeting unconsciously, seeing groups as criminals or suspects. These kinds of impulses can result in innocent people ending up dead.

Kristen: You’ve suggest creating racial affinity groups. When I first read this it seemed counterintuitive. How is it going help racism if I, as a white person, go and convene with a bunch of other white people? But I now realize it’s because I’m not ready to have this conversation yet, until I do my work, until I unpack it and ask myself: What is it that we have been perpetuating? What have we as a collective been ingrained with?

Ruth King: …What’s the programming?

Kristen: Let’s dive into racial affinity groups…

Ruth King: In the book I’m talking about two structures that are important for us to awaken to and explore our conditioning. One is meditation and the other is what I refer to as a racial affinity group.

It’s a mindfulness structure where white people get together with other white people and people of color get together with other people of color, in their own race ideally, and they begin to have some very intimate conversations about how they’re thinking, what they’re believing, how they’ve been conditioned. A racial affinity group does a number of things, but it especially supports white people in waking up to their own racial group identity — to grasping whiteness.

The work is understanding themselves as a collective and the collective impact that they have in the world. The white conversation is not one that we’ve heard much about. I’ve had so many white people say to me, “When I get together with other white people, I don’t know if we can have this conversation without people of color. I feel like they need to teach us.” My response: No, you need to learn about whiteness. You need to learn about why it’s difficult to be with other white people and talk about race.

Kristen: You really have to have a willingness to explore this and to ask yourself, what’s popping up in response? What was the conversation in your house growing up?

Ruth King: In the book there is a very prescribed structure, a simple way to set up a racial affinity group. You get together with three to five people. You commit to this inquiry for about a year. You can meet once a month for a few hours and there are specific questions, about 50 questions, that over time you begin to talk about. There’s a structure around safety, confidentiality, and how you support each other in these groups.

But what’s so important is that you have a safe place where you can begin to explore your racial conditioning, where you don’t have to be blamed, shamed, or defend yourself and so on. People of color need to do this as well, because our focus often has been on things outside of ourselves. What people of color share in common is oppression. So, it’s a similar issue, but different.

Kristen: The construct of a racial affinity group gives us something to like latch onto. It gives us a sense of hope that we can do something here.

Ruth King: That’s right.

Kristen: It felt like we were making progress and yet, in terms of racism, I think we’re in pretty dire straits right now. It feels like society has kicked a hornet’s nest and we need to come to the table to do something about it.

Ruth King: There’s a lot that needs to be done. I mean, the book is not intended to stop people from doing their social activism work, but it is an opportunity for people to look at how they’re going about doing that and the character that they bring to social justice activity.

Everything we see is a projection of heart and mind. I want people to really connect the dots to see that the stuff that’s happening on the outside is also in here — and we need to have a different relationship on the inside.

Kristen: You’ve given us tools and ways in which we can avoid retreating and lashing out — strategies to avoid leaving our bodies and leaving the room — showing up for this conversation. Bottom line: You give us hope.

You write, “Even though this book is not about eliminating racial justice or solving social inequities, we can be helpful. Racial distress can be useful. It invites us to question how we live our lives. We can become more choiceful through mindfulness practice. We can stop the war within our own hearts and minds.”

And if we can stop the war within our own hearts and minds, then we can let that trickle on down. Right?

Ruth King: Yes. I think we have to think about what is our vision of racial healing? A part of me wants to make sure nobody feels afraid of having this conversation, even though I know fear might be there.

But my prayer is that we can engage each other at such a human level that nobody has to shrink and run to their corners and protect themselves. No one is in danger. That’s my hope in this book in a large way — that we’re developing some skills and some awareness to understand the human condition and to bring the heart right into the center of it, so that we don’t forget that we belong to each other.

Kristen: May the heart opening begin and the true healing emerge.

Thank you, Ruth, for your courageous work in this realm — and for your voice and your candor and willingness to have this dialog. I was initially going to have you guide us in a meditation to close our conversation, but that was until I read the last passage in this beautiful book which just cracked me open. I would love for you to give closure by reading it.

Ruth King: Oh, it would be my pleasure.

May we understand and transform racial habits of harm.

May we remember that we belong to each other.

May we grow in our awareness that what we do can help or hinder racial wellbeing.

May our thoughts and actions reflect the world we want to live in and leave behind.

May we heal the seeds of separation, inherited from our ancestors, in gratitude for this life.

May all beings without exception benefit from our growing awareness.

May our thoughts and actions be ceremonies of wellbeing for all races.

May we honor being diverse racial beings among the human race and beyond race.

And may we meet the racial cries of the world with as much wisdom and grace as we can muster.

Kristen: I’ve never cried in an interview, but there’s a first for everything. [hugging]

Your voice is salve for the soul. And every person needs to get this book in their hands.

Ruth King: Oh, great. I agree.

This has been beautiful. Thank you so much.

—