Mark Hyman, M.D.

FOOD: Unraveling the Confusion

April 12, 2018, New York City

Photographs by Bill Miles

Your fork is the most powerful tool to transform your health and change the world.

~ Mark Hyman, M.D.

Kristen: Thank you for inviting Best Self into your home today. Our paths have crossed many times over the last couple of years, but I’m very excited and honored to be here today and to have the opportunity to celebrate your incredible work in the world.

Mark: Thank you.

Kristen: So before I get started, I think I should make a proper introduction to our audience.

Dr. Mark Hyman is a man on a mission with a desire to set the record straight about all things food. Systems, policies, and its connection to the environment, economy, social justice, personal health… and helping us figure out what the heck we should be eating in order to live healthy, vibrant lives.

Doctor Hyman is the director of the Cleveland Center for Functional Medicine, Chairman of the Board for the Institute for Functional Medicine, and Founder and Director of the Ultra Wellness Center.

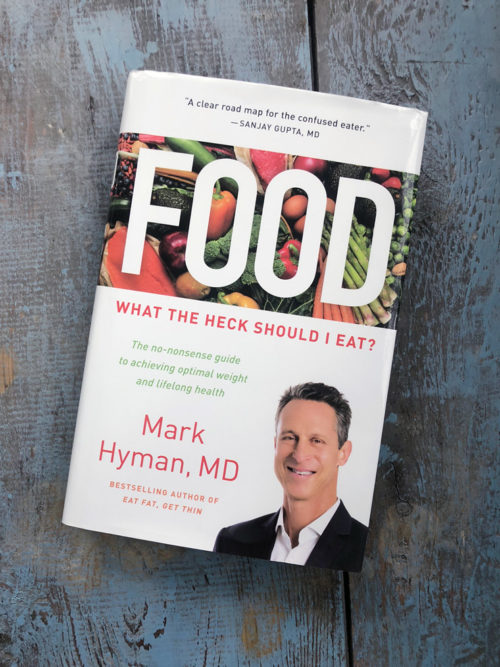

He is a 10x number one New York Times best-selling author, and an internationally recognized leader, speaker, educator, and advocate in his field. His latest book Food is truly an ode to demystifying and debunking food myths, discerning complex science, and making sense of it all. Thank God!

So, with no disrespect intended, I have to say this book is really good. Not that I didn’t expect you to write a good book, but I was really surprised to have been captivated by a book about food.

I’d love to start with understanding more about where this journey started for you. Mark Hyman decides to go to medical school, but how does that lead into Functional Medicine? And where does Mark Hyman make the connections to identifying that food really is the key to health and wellness?

Mark: It’s a great question. It actually started before medical school, when I was in college at Cornell. I moved into a house with a bunch of folks and one of them was a PhD student in nutrition. He was studying the role of fiber in gut flora, which I thought was pretty fascinating. And remember this was four decades ago.

Kristen: Right, nobody even knew we had gut flora at that time! [laughing]

Mark: He gave me this book that changed my life, which was called Nutrition Against Disease by a guy named Roger Williams. He was one of the fathers of the notion of biochemical individuality: how we’re all different, and the notion that we can change disease, particularly chronic disease, by what we eat. That book set the framework in my mind of perceiving food as medicine.

At the same time I was also studying systems theory and systems thinking, and the connections between different healing systems and how the body works. That all blended into this predisposition to think differently about the body and health and healing. I actually majored in Chinese and was going to go to China to study Chinese medicine, but decided I didn’t want to spend my 20’s in a fascist dictatorship.

So, instead I decided I’d apply to medical school and see if I got in. At the time I was majoring in Buddhism, which is a revolutionary way of thinking about how our suffering and perceptions work. I studied the Medicine Buddha, which was all about how we actually have to rethink our relationship to our bodies, our health, our world, and ourselves. With that I went to medical school and I got kind of brainwashed for the first bit.

I just decided to suspend all of my previous thinking and take in this system as whole and see what happened. I became fascinated with the body from that perspective. I had a great time in medical school, became a family doctor, and was always focused on nutrition and health and wellness. In my own life, I was a yoga teacher before I was even a doctor — that was like 40 years ago when nobody was even doing yoga. I went to a yoga studio here in New York City. At the time, there was one yoga studio with about 5 people in it. Today, you’re lucky if you can get a spot in a class even if you go an hour beforehand. [laughing]

Kristen: We’ve come a long way baby!

Mark: And then when I was 36 years old, I got really sick and ended up having a complete collapse of all my systems as a result of mercury poisoning from when I lived in China. That led to my having to figure out what was going on, because no one could help me. No traditional doctors were helping me. I had gut issues, cognitive issues, severe muscle pain, and autoimmune disease. All these things were happening simultaneously.

Through that process I discovered this new model of thinking called ‘Functional Medicine’, which is a systems approach to disease; it’s looking at root causes. It’s really the science of creating health as opposed to just treating disease. It asks the question, Why? Why is this occurring? Instead of, What disease do I have?

In traditional medicine we are more focused on What: What disease do I have, what drug do I give based on symptoms and geography. As opposed to new thinking where the microbiome teaches us that your gut flora may cause depression and autism and cancer and heart disease and diabetes and obesity and on and on and on — which doesn’t make any sense within our current framework of disease.

You don’t go to a rheumatologist and hear them ask, “Well, how is your gut flora?” Or the cardiologist and hear, “Well, what’s going on with your gut?” But that’s actually what the future of medicine.

Functional Medicine is a way of shortening the gap from the science to the practice.

Kristen: First of all, as I’m sitting here listening to you I can’t help but think of you as a college student and note how fortunate you were to have come in contact with this information so young in your life. I wasn’t previously aware of your health issues, but can only imagine that all that came before culminated in setting the stage for you not laying down on getting answers. I can only imagine the tests the traditional doctors must have run you through.

Mark: They wanted to give me anti-depressants, anti-anxiety medication, sleep medication, pain medication. I thought this is really horrible and was like, No, no, there’s something going on here and I’m not depressed, I know what’s going on.

Kristen: How fortunate that you had this sort of yin/yang, Eastern/Western sensibility and approach and that it planted seeds in your life to seek out more. You probably didn’t really know what you were going to do with it all, but it seems like it all came together when you needed it most.

Mark: Yes, through the retrospective-scope you can see how everything connects in your life. It’s understanding the flow of your life and following different doorways and actually seeing how they all connect looking back. Everything I didn’t learn actually set me up for rethinking the way things are and asking the right questions. So, this is really all about a rethinking of disease and health.

We know that the most powerful drug on the planet is food.

We had a woman in one of our groups at Cleveland Clinic recently who had been on insulin for 20 years, a Type 2 Diabetic, and within three weeks she was completely off insulin and medications, and her blood sugars were normal. That’s the power of food. There’s no drug that can do that.

Kristen: This notion of food as medicine is a discovery that I only made in my own life maybe five years ago. I had previously pegged food as good and bad — but never really understood that connection of food as medicine. As you say, the most powerful tool that we have is our fork.

Why are we not making these connections?

Mark: We’ve all been taught that food is energy, that it’s calories, that you need it for sustenance to keep things going, but that aside from that, as long you don’t eat too much, and as long as you exercise enough, then everything’s fine.

Kristen: As long as I’m thin, then all is well, right?

Mark: There are a lot of people who are thin and are not healthy. So, it’s not necessarily equated to thinness. It’s the idea that food is actually more than calories, that it’s not all about exercising more and eating less; it’s actually about the quality of the food and what that does to your biology that matters.

You think about 1,000 calories of broccoli and 1,000 calories of soda — are they the same because they have the same amount of energy? No, they’re different because they have different effects on your biology. In a laboratory when you burn them they’re the same in a vacuum, but we’re not in a vacuum — we’re a living, breathing, dynamic organism. So when you eat different food it has information and instructions, like an operating system programming your biology with every bite. It doesn’t happen over decades, it happens over minutes in terms of your gene expression and your hormones that get produced.

If you eat sugar, your stress hormones go up; if you eat fat they go down. If you look at how it affects your immune system, it regulates inflammation — food is either anti-inflammatory or inflammatory depending on what you eat. It affects your brain chemistry whether you produce happy mood chemicals or depressed chemicals. It affects behavior. We know that violence can be caused by the wrong kinds of foods. We know it also affects your gut microbiome with every bite.

So with literally with every single bite of food, you’re giving your body instructions to either create disease or create health in real time, and it’s powerful.

Kristen: And it’s simple.

Mark: Yes. Focus on what you eat; you don’t have to worry about how much. How many people are going to eat 10 avocados? Nobody’s going to do that. But you can easily eat 10 cookies, right?

Kristen: You work with individual patients and you work with organizations. You’ve worked with policy makers, influencers. You’ve collaborated with fellow leaders in the field, you’ve worked with testifying before the White House Commission and the Senate. You’ve also consulted with the Surgeon General, advised world leaders, politicians, and celebrities. And you’ve even introduced the Enrich Act to Congress with our friend Congressman Tim Ryan to fund the inclusion of nutrition into medical education.

This is such a shocking statistic. Can you tell us how much nutritional educational is included in the curriculum of Western medical studies?

Mark: I think relevant nutrition education — almost none. Less than 25% of medical schools have the recommended nutrition hours within their curriculum, according to the National Academy of Science’s recommendations. When you include the hours that are actually given, they’re mostly about nutritional deficiency diseases, about managing people on feeding tubes. It’s not about using food as medicine.

Kristen: When you got sick, where were you in your life? Were you in med school? And how did you start navigating your way out of that?

Mark: I had been working for a number of years as a family doctor when I got sick.

I was really fortunate to have been introduced to a guy named Jeffrey Bland who studied with Linus Pauling, the PhD Nutritional Biochemist, who in my view is one of the smartest and most prescient thinkers in medicine. The ideas that he introduced me to 20 years ago are just now becoming understood in medicine as relevant.

He presented a paradigm of medicine that was really different, and I thought, this guy’s either crazy or he’s really onto something. And if he’s right, I owe it to my self and my patients to do something about it. So I started voraciously consuming research, learning and studying. In doing so, I realized there was a different way of thinking about disease. It was like learning a language, and I finally got it and started to try this with people and saw extraordinary results — things that I could never imagine possible as a traditionally trained doctor.

Kristen: You also mentioned in the book that you have 35 years of nutritional study.

Mark: 40 now. [laughing]

Kristen: Okay, 40. You have a lot of nutritional education. But even with that, you state that the science is still confusing to you. So, if you don’t understand it how are we supposed to understand it?

Mark: Well, I think it can be confusing because of the way the science is done. When I was in medical school I thought science was this pure, unbiased field of truth. And what I learned is it’s often very corrupt depending upon who funds it.

Marion Nestle was a nutritionist at New York University who is now writing a book talking about how the food industry corrupts nutritional science by funding studies that obfuscate the truth on purpose and then promote them and market them. Soda companies study obesity and find there’s no link between soda and obesity. The Dairy Council funds studies on dairy finding that it’s nature’s perfect food. Independent studies find the opposite.

Kristen: They cherry pick their science.

Mark: Yes. 99% of the studies on artificial sweeteners done by a food industry find they’re safe. 99% of studies done by independent researchers find they’re harmful. So that’s the kind of stuff we’re battling.

Plus we have to look at how they were designed; what the population was, when it was done, whether it proves cause and effect, what the basic science is. And that’s really not part of the conversation for most people.

Meat is a great example. We’ve been told that meat is bad because we believe that meat contains saturated fat; saturated fat is bad, hence we should not eat meat. Well, there was no proof of that. It was all based on some very poorly done studies that show that saturated fat may be correlated with heart disease, which turns out not to be true.

And when people were looked at who ate meat over long periods of time, the data from hundreds of thousands of people who took food questionnaires every year, the one’s who ate meat seemed to have more disease. But it turns out, when you look at the characteristics of many meat eaters, these are people who weren’t concerned about their health. Statistically, these people smoke more, they drink more, they eat less fruits and veggies, they don’t take their vitamins, they don’t exercise, they drink more alcohol. Of course they have more heart disease!

The people who didn’t eat meat were considered more healthy, but they were biased actually, and considered healthy because they exercised, ate well and avoided meat — but it wasn’t the meat that was the problem.

So we get really confused by these kinds of studies, and the average person doesn’t have the scientific training to actually understand this. Even most doctors don’t.

Kristen: And when a study comes out, somebody in the general population has to dig in and find out who’s actually behind the study. When did food get so complicated?

Mark: We didn’t really need doctors or nutritionists to tell us what to eat for most of our history of humanity, right?

Kristen: Right.

Mark: And now everybody’s confused. I think that’s really why I wrote the book. The government tells us guidelines that don’t match the science. The media is also confusing us. The science itself is confusing. The food industry has got their finger in there. So it’s a mess.

I really sifted through it and all the controversies. People ask me, “What about this? What about that? Should I eat this? What about vegan? What about paleo? What about dairy?”

Kristen: So, what about all of those? How are you eating now? Are you a vegan or a vegetarian?

Mark: When you look at the data you can believe anything. If you’re a vegan you can say, if you eat meat you’re going to die, it’s going to kill you. If you listen to the paleo folks, if you eat as a vegan you’re going to get sick and be nutritionally and protein deficient and die. They both can’t be right, right?

So what is the truth that we know about nutrition? What can we distill it down to? What are the principles that are flexible, that can accommodate a wide variety of diets that aren’t rigid, but that are based on good science?

I was sitting at a table once with a vegan cardiologist and a friend of mine who’s a paleo doc who were fighting like cats and dogs. I interjected, “Well, if you’re paleo and you’re vegan, I must be pegan.” I said it as a spoof. I mean, we certainly don’t need another diet. But what I realized is that it’s not a diet, it’s a set of principles, and they’re things that almost everybody agrees on — including the paleo and vegan communities and everybody in between.

Kristen: WOW. There is a God — something they can agree on.

Mark: Exactly. So I basically just synthesized the research into 12 really simple principles that people can follow:

One, we should eat foods that are low glycemic. There is a powerful driver of all chronic disease: sugar and starch. These are foods we’re eating in pharmacological doses — 152 pounds of sugar, 133 pounds of flour each year per person, that’s average. And we know that causes diabetes, heart disease, cancer, dementia, depression, and much more. Nobody’s going to disagree with that.

Second, we should be eating foods that are mostly plants. So we call it a plant-rich diet, not plant-based. 75% of your plate should be non-starchy vegetables, some fruits, but not high amounts of fruits because they can be high glycemic if you binge on tons of pineapple or grapes. And we should be eating a lot of good fats: avocados, olive oil, nuts and seeds. Nobody disagrees with that. Some people disagree on the saturated fat question.

The other thing is we should be avoiding refined oils and refined foods in all forms. I think nobody thinks we should be eating a diet that’s rich in pesticides and herbicides and antibiotics and hormones, full of additives, chemicals, preservatives and dyes. We eat 3,000 food additives in our average diet, and we eat about three to five pounds per person per year of food chemicals, food dyes for example. That’s never been looked at as a cohesive issue, and it’s a big problem linked to all sorts of behavioral and cognitive issues.

We should be eating a lot of nuts and seeds; everybody agrees that those are beneficial and healthful. If we are eating animal products, we should be eating foods that are grown in a way that restores the soil, a way that preserves water and doesn’t treat the animals inhumanely. That’s what we call regenerative agriculture.

Kristen: I really believe that there is a disconnect between what is on our forks and how it affects our planet, not just our physical health.

Mark: I was ambitious in this book to try to make a simple practical set of tools that people can use when they go to the grocery store.

Kristen: By the way, I think you need to do an app, because I think it’s so practical and so well done that I would love to be able to pull it up on my phone.

Mark: Well, if you go to FoodTheBook.com you can download the ‘Food Road Map’. I synthesize the entire book into one simple page.

So, for example if you’re going to eat meat, here’s what you need to know, don’t eat that / eat this. If you’re going to have dairy, here’s what you need, don’t eat that /eat this.

Kristen: …look for these labels, etc. I appreciated the section about barbecuing — which marinades are helpful and the benefits of infusing things like garlic and rosemary.

Mark: I also tried to make it really practical, to connect the dots for people to understand that what they’re eating isn’t just a personal choice, that it affects the soil, it affects our water shortages globally, it affects the climate change, it affects environmental degradation from nitrogen runoff into the rivers and streams and lakes that kills huge amounts of life — which lead to dead zones the size of New Jersey.

It leads to educational challenges because kids are too sick to learn and then have achievement gaps where they end up having poor lives, are less successful and less likely to go to college. Where we have more poverty and violence and social injustice because of how our food system targets the poor and minorities. Where we have even national security issues because kids are too sick and fat to fight — 70% of military recruits get rejected in the south.

And it affects the economy, which is so burdened by Medicare and Medicaid. By 2042, 100% of our entire federal budget will be Medicare and Medicaid. Now it’s a third of most state’s budgets. It’s the biggest driver of our federal deficit, yet nobody’s really talking about it because of the chronic disease that affects one in two Americans that’s driving all of our economic crises.

Kristen: In terms of making those connections that you’re talking about, from our fork to the planet basically, meat is a really good example. It’s so difficult to figure out if it’s okay, where do I get it, what does it have in it, does it have antibiotics that are now going to get passed to me. So, I appreciate how you broke down all the chapters and gave all these really tactical tips like looking for the ‘American Grass Fed’ label.

Mark: I think we have been told that meat is a problem for the planet, it’s a problem for our health, and there really are three issues when it comes to meat. I want to live to be 120, so I wanted to know if meat was something that I should be eating. I didn’t want to rely on other people’s opinions. So I literally pulled all the best research on meat, it was a huge stack, and I locked myself in a hotel room for a week and I read it all. I studied it, I compared it, and I looked at the patterns, at the other issues around environment and climate change and so forth.

Kristen: You geeked out.

Mark: I totally geeked out.

I realized there were three issues. One is moral. I mean if you’re a Buddhist monk, and I have Buddhist monks as clients, then you don’t have to eat meat. Then there’s the environment issue, which is a big one because factory farm animals are bad for the planet in so many ways (I’ll get into that in a minute), and the third is health.

The data is pretty clear on the health issue. There is actually no long-term harmful effects from eating meat, and there are probably a lot of beneficial effects. The big question is, what is the quality of the meat? Is it factory-feedlot meat? Is it a factory- farmed chicken? Is it a factory-farmed fish? Those are not great for us for a lot of reasons. From health points of view and from animal rights points of view.

As far as the environmental issues go, people say, “Well yes, meat is bad for the environment.” And I would agree; I think the way we grow meat in the planet is harmful. 70% of the world’s agriculture lands are used to grow food for animal production. 70% of our fresh water, which is only 5% of the world’s water supply, is used to grow animals. This is a bad idea.

Plus, the way we grow the food depletes the soil, which then leads to the inability of the soil to hold carbon. This is important because if carbon is released into the environment it causes climate change. Soil is one of the biggest carbon sinks. The rain forest is as well, but so is the soil, in fact it may be even more important. We till the soil, we erode the soil, and as a result we’ve lost over a billion acres to erosion and desert.

Kristen: And we deplete the nutrients.

Mark: We grow food in depleted soils. We see droughts and floods because when the water hits these depleted soils it can’t hold the water and it will run off and cause floods.

The way we use pesticides and herbicides, basically the nitrogen from industrial farming goes in the rivers and lakes and causes an over growth of algae, which then kills the oxygen.

It’s a bad system and it’s causing enormous environmental destruction. When you look at the entire food system as a whole, including food waste and all the components, it’s the number one cause of climate change.

So I agree, we should not be eating factory-farmed animals. But then the question is what about meat? If you look at the research on regenerative agriculture, it’s really amazing. When you use animals to graze on lands, it can restore the soil. We had 60 million bison in this country 150 years ago. We killed them all to get rid of the Native Americans. And they produced tons and tons of top soil, literally 20-30 feet of top soil in some areas in America. Now we’ve eroded that.

But it’s not the animals themselves; it’s how we raise them. We have 80 million cows, but if they were on grasslands — and we can sustainably raise them on grasslands — we can raise them in ways that are better for us, better for the planet. It actually can help restore the soil. Estimates suggest that by doing this at scale, we can bring that carbon in the environment to a pre-industrial time, basically completely reversing climate change.

But nobody’s really connecting the dots. People say, “Oh we should eat less meat.” Well yes, the wrong meat — but the right meat, if we eat more of it and we actually change our agricultural model and we support that with subsidies instead of factory farming, we have an opportunity to make a huge impact on our health and the health of the planet.

Kristen: And again, it’s about making that connection — asking where what’s on my fork came from and how it got here. You also had some pretty shocking information in the book about how some farm-fed cattle were being fed candy still in wrappers…and it’s legal.

Mark: They’re fed stale candy. They’re fed ground up animal parts, all kinds of junk. And you know: You are not what you eat; you are what you are eating ate.

Kristen: Which also leads into how they are force-fed antibiotics.

Mark: Yes. Antibiotic use in animal husbandry is a real problem because we’re seeing tens of thousands of deaths a year from antibiotic-resistant bugs that are caused by factory farming.

Kristen: So let’s also talk a little bit about how we’re being led down a path, how diet fads evolve and how everybody sort of jumps on board with something.

You say in the book that the food industry has invited itself into our homes and encouraged us to outsource our food and cooking. This has been the breakdown of so many things, in particular the family dinner and our relationship to food.

Mark: This is actually fascinating: how did we move away from families cooking at home? In 1900, 2% of meals were eaten outside of the home; today it’s 50%.

Kristen: Think of the tradition that went along with that. Think of your grandmother’s kitchen — you remember the smells, the certain foods, the traditions.

Mark: And then after World War II, there was the rise of the processed food industry, and there was an interesting movement at the same time to empower people to cook at home. They had federal extension workers who would go around to new families and teach the families how to cook and grow gardens and make real food.

There was a woman named Betty who was a home economics teacher who was very passionate about this and very vocal about it. The food industry got together and said, “We can’t have this, we have to figure out how to get our products out in the marketplace.”

So they decided to create this culture of convenience. Convenience became the prime value that we adhered to, and when that happened we started insinuating processed food into our products at home. Remember ‘Betty Crocker’?

Kristen: We’re aging ourselves by saying we know who Betty Crocker is. [laughing]

Mark: My mother had the Betty Crocker Cookbook.

Kristen: Whose didn’t?

Mark: …and there was a picture of Betty Crocker on the front of the cookbook, and I thought Betty Crocker was a real person.

Kristen: So did I.

Mark: Turns out she was a fabrication of the food industry. So General Mills convened a group (which now would probably be an anti-trust issue)…

Kristen: …which was a brilliant strategic marketing idea.

Mark: …to get them to actually create this culture of convenience. It started with things like the Betty Crocker Cookbook, which you may remember was filled with the recipes that included ingredients like a can of Campbell’s Cream of Chicken soup, Velveeta cheese, or Ritz crackers. Then they moved onto TV dinners and to more and more processed food and more fast food, and ultimately we end up having this culture where Americans don’t know how to cook anymore. They’ve literally hijacked America’s kitchens, our taste buds, our brain chemistry, our metabolism, and we need to take them back.

Kristen: Hijacked by convenience… and Betty!

Mark: Yes, and the family dinner has been disrupted. The average family eats dinner 20 minutes three times a week at most, each eating a different food from a different factory that’s processed, packaged, and put in a microwave. That is not a family dinner. All of this while they’re watching TV or are on their phones. And that breakdown has led to the breakdown of many important things.

We see kids having more trouble in school, more behavioral issues, more anorexia and bulimia, more obesity. We need to inculcate our kids with values and teach them about food and how to cook. I cooked dinner every night with my family even though I was a busy doctor.

Kristen: In the vein of moving towards ‘real’, in your book you alluded to the idea that we shouldn’t be eating things that perhaps we didn’t find in our grandmother’s kitchens or our great-grandmothers kitchens. Right?

Mark: Yes. Michael Pollan has a great book called Food Rules. One is: If your grandmother wouldn’t recognize this as food you shouldn’t eat it.

Kristen: If it has 37 ingredients, it’s not a food.

Mark: Right, it’s a food-like substance. If the cereal turns your milk a different color, you probably don’t want to eat it.

Kristen: Let’s talk about cost. People always say things like, “Yeah, that’s great for them to say, but organic is really expensive. I don’t have a Whole Foods or I don’t have a health food store, or I don’t have access to purchasing something online from a resource.” How do you speak to that?

Mark: It’s a real problem. There are areas of food insecurity and food deserts in America where there are 10 times as many fast food convenience stores as there are grocery stores. But the research has shown that the average cost of actually eating well is about $1.50 a day more. We actually know how to eat well for less, and I think it’s a hierarchy party.

Not everybody has to eat a grass fed $70 rib eye steak, right? And nobody has to have heirloom tomatoes. We can eat real food first. I think the first hurdle is getting off of processed food, getting off of fast food and eating real food.

I had a real awakening when I was part of the movie Fed Up, which is about the role of the food industry in pushing sugar and low fat foods and driving the obesity epidemic. As part of the movie, I went to see this family in South Carolina in one of the poorest communities and one of the worst food deserts in America. This family of five lived in a trailer.

Kristen: Please define what a food desert is, in case someone isn’t familiar with the term.

Mark: A food desert is essentially a place where it’s really hard to find real food. You can go and get processed food in a convenience store, but you’re not going to find a lot of real healthy food.

This area I visited has 10 times as many convenience stores and fast food restaurants as grocery stores, and the family lived on a budget because they were on food stamps and disability. The father was 42 and on dialysis for kidney failure from diabetes. The mother was 100+ pounds overweight. The son was 16 and almost diabetic, very overweight. I went to their house, and instead of telling them, “Here, you should eat better,” I said, “Let’s make a meal together.”

So we went shopping, we got real food. I used a guide called Good Food On A Tight Budget, which is from the Environmental Working Group where I’m on the board. We made real food with the cheapest, healthiest grains and beans, with the cheapest, healthiest nuts. In every category of real food, we choose one of the cheapest forms that are still good for you and good for the planet and good for your wallet. And I said, “Here’s how we cook.”

They didn’t have anything in their house that was real. Everything they thought was healthy was a result of the way they were marketed to. They didn’t know that their salad dressing was full of high fructose corn syrup and refined oils and gums that cause leaky gut. They didn’t know that their Cool Whip said zero trans fat on the label, but because of a loophole in the labeling laws, that it was all trans fat and all high fructose corn syrup. They didn’t know their Jiffy Peanut Butter was full of trans fats and high fructose corn syrup.

They didn’t know how to chop a vegetable, they didn’t have cutting boards, they didn’t have knives…they just didn’t know.

Kristen: And they’re not alone. You’re not shaming the family.

Mark: No, I’m shaming the food industry, which has deliberately perverted our food system.

It was really an eye opener understanding that Wow, they really didn’t know. So we made this simple meal of turkey chili. I made a salad with real lettuce, not iceberg lettuce, just olive oil and vinegar, salt and pepper dressing. We chopped garlic, we chopped some onions, we roasted some sweet potatoes. We had to cut our sweet potato with a butter knife because they didn’t have a cutting knife, and we roasted them with herbs in the oven. Very simple, easy to make food — and they loved it and thought it was delicious.

I gave them the guide and one of my cookbooks and told them, “You can do this.” And they did it. They lost a couple hundred pounds in the first year; the son lost 50 and then gained it back because he went to go work at Bojangles — because there’s nowhere to work as a teenager down there. But he got himself together and he lost 120 pounds and is now going to medical school. If they can do it, anybody can do it.

Kristen: How awesome. And that’s the point, despite living in a food desert…

Mark: …in extreme poverty

Kristen: …it is possible and it planted healthy seeds for them.

Mark: I go through that in the book. One of the best sources of cheaper healthy food, for example, is Thrive Market, which has awesome food at 20-50% off of prices you’d find at Whole Foods. You can find out how to get even grass-fed meats at a great discount by cutting out the middle man and going right to the farmer. There are ways of getting ingredients from all sorts of resources.

Kristen: It’s getting much better, but we’ve still got a long way to go.

Kristen: Piggy backing on teaching people how to read labels, it’s really alarming to think that we can’t trust things like the American Heart Association check mark. Can you talk about that for a second?

Mark: The other thing that’s made us confused is the subversion of public health organizations and advocacy groups by the Food Ministry. For example, a large portion of the budget of American Heart Association and the American Nutrition Dietetic Association and the American Diabetes Association, American Cancer Association — come from the food industry.

Look closely at certain products in the grocery store that have the American Heart Association seal of approval. For example Trix, ‘Trix are for kids’, right? There are seven teaspoons of sugar per serving, there’s so many different kinds of dye, red dye, blue dye, yellow dye — basically you eat it you die — and it’s an unbelievable thing.

They can actually put that seal of approval on that food, and yet if it has any fat in it they say it’s bad. Your low fat yogurt is considered heart healthy. When you look at the ingredients, ounce per ounce, your low fat, sweetened fruit strawberry yogurt has more sugar per ounce than Coca-Cola, but they put their check mark of approval on it. It’s frightening.

So we have to understand that our Public Health Organizations have been subverted and are not actually telling us the truth. On top of that, advocacy groups like ‘Feeding America’, which is a hunger group, have been co-opted by them so they don’t want to promote soda taxes, for example, or promote food stamps not being used for soda. We have the NAACP and Hispanic Federation funded by the soda industry, which is why they come out against the soda taxes, even though their communities are far more affected than any other communities in terms of their levels of obesity and diabetes because of their use of these products.

It really needs to be addressed. We need to protect these groups and our government needs to step in and regulate these things so we don’t have undue influence from industry shaping things and marketing to target these populations.

Kristen: Cost is a big reality — but so is the cost of our health. How much does that medicine and that dialysis, and all of that end up costing us?

Mark: That’s true: you pay now or pay later. Your cost of medication and of being sick and off work and disability and that quality of life — those are the externalities we don’t include in our thinking.

The other issue is that we don’t want to include the true cost of the food in the price.

So what is the true cost of a can of Coke? Well, when you count how we grow the corn for the corn syrup and how it depletes the soils and contributes to climate change and degrades the environment, those costs aren’t included. When you count the cost of chronic disease, disability, productivity in the workplace, and how it affects Medicare, Medicaid, our overall economy. Those things aren’t included in the price. If we did, then a can of Coke might be $10 or $20.

Kristen: I was thinking it would be about $550.

Mark: So maybe grass fed steak would be a lot better deal. And if we actually included the cost of the savings to health and environment by eating different foods and put those as discounts on the healthy foods, we’d see a big shift.

In fact, there are proposals in Congress to actually make food stamps more expensive to buy junk food. And by the way, the number one item on food stamps is soda. If you look at junk food as a whole, it’s probably tenfold as a category more than any other category of food that is purchased with food stamps. If we actually make it more expensive to buy that stuff and less expensive to buy fruits and vegetables and whole foods, that would shift purchasing patterns and make a big difference.

Kristen: Right. But the beautiful part of the story you shared is that this family started to sit down and prepare a meal and started to see the results of how that made them feel — emotionally, physically, spiritually. Also how they started to feel about themselves, how they started to go out and interact in the world, I think that starts to empower people to demand more.

Mark: Absolutely.

Kristen: There’s so much that we can go into here today, and it’s in the book, and it’s fascinating. You just put it all out on the table. You call everybody out on their bullshit, on demystifying the myths and the lobbyists.

Mark: It’s all in there, but at the end of the day, it’s a very practical guide. So you can get all into the issues of the environment and the politics and the policies, but at the end of the day it’s really meant to be a practical tool.

Kristen: It’s not about shaming, it’s about empowering — it’s empowering us to re-navigate our relationship to our food and what we put on our fork and how that attaches to everything else.

Mark: People may feel powerless in this world — powerless in politics, powerless over the economy, powerless over the environment — but the truth is we are enormously powerful because we vote three times a day with our fork. We vote for its impact on our health, on our planet, on the economy, on politics, on social justice. All these things matter and give us an enormous power.

Imagine what would happen if everybody on the planet decided to not eat any processed food for a day. Everything would change.

Kristen: And let’s be real — if you’re telling me that changing my diet can change my world —why wouldn’t I try it? What do I have to lose?

Mark: You could listen to me talk all day and that probably wouldn’t change anything, but that’s why I encourage people to do a 10-day reset. In the book there’s a 10-day reset where you basically take out all the bad stuff and you put in the good stuff and see what happens.

Kristen: Is coffee on that list?

Mark: You could keep coffee, but generally I tell people to just get a break and see what happens. People use it for energy, but actually often people’s energy is worse on coffee and it’s better when they get off coffee.

Within 10 days you’ll see profound changes. We saw a 62% reduction in all symptoms and all diseases in just 10 days of this clean eating. Migraines, joint pain, fatigue, irritable bowel, allergies, sinus issues — in 10 days people see dramatic improvement.

You don’t have to listen to me, listen to your own body.

Kristen: Do you think people are unaware of the connections?

Mark: People do not connect the dots. I see patients from all different walks of life and even the most educated and intelligent people don’t connect what they’re eating with how they feel.

The only way to do it is to radically change your diet. You can make incremental changes, but they won’t work. Let’s say if you’re reacting to dairy and gluten and you just cut out dairy, “Well I still feel sick.” Well, yeah of course, because you’re not getting rid of all the things. You’ve got to do a radical reset and then you’ll know, and you don’t have to just listen to me.

Kristen: I love this book. I love your work. I am really thankful for the opportunity to sit down with you and have this conversation.

I really want to thank you for walking the walk and talking the talk on behalf of us all, because you’re really cracking it open, planting seeds, sparking something that we can all take charge of. Like you said, we can find our voices, find our power, and become more healthy and vibrant.

Mark: That’s the goal.

Kristen: I want to end with one parting question for you: If you could close your eyes and wave your magic wand right here right now, what would you change? What would your vision for the future be in regards to your work?

Mark: I think it would be to empower people to understand how the choices we make really matter. If I were King for a day, I would probably do a sweeping set of policy changes where I create an inter-governmental food agency or food commission to look at these issues as an integrated global problem. I would change the subsidies to support regenerative agriculture and remove them from industrial agriculture. I would change our dietary guidelines to match the science and not be corrupt and confusing.

I would end all food marketing to kids, as well as for all junk food and any food that doesn’t promote health. I would implement soda and junk food taxes, which have worked around the world. I would have a radically different approach to food labeling that makes it clear what people are eating, like in many other countries. In Chile they put warning labels, like on cigarettes, on breakfast cereal for kids. In other countries they have a stop light symbol: green is good, red is bad, yellow is eat with caution. I would make it really clear. And get money out of politics.

Kristen: You have my vote for King for the day.

Thank you so much, Mark.

Mark: Of course! Thank you, Kristen.