Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Learning to surf becomes a means — and a metaphor — for processing emotions and finally embracing a healthy, non-toxic masculinity

—

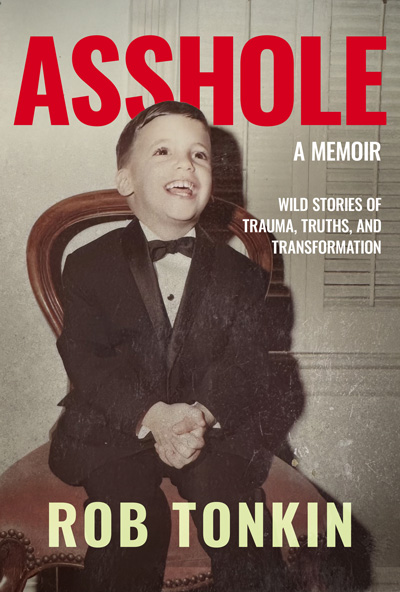

When I was 43, I learned to surf. It’s an unlikely hobby for a man who spent 20 years terrified of the ocean, but it was a crucial step in confronting the fears and emotional baggage that had been holding me back for decades. This journey is just one of many I recount in my memoir, Asshole. This book also explores my wild ride as a radio dj and music promoter, the celebrity encounters and sexcapades, the cycle of getting fired and bouncing back, and ultimately, the long and painful process of losing and finding myself. Through it all, surfing taught me that true strength isn’t about ignoring your fears; it’s about facing them head-on.

The ocean had become a symbol of my trauma, tracing back to a terrifying childhood incident and a near-drowning experience in my twenties. I was trapped in a kelp bed, panicking, while a friend watched from shore with a cold indifference that mirrored the unsympathetic behavior of my father years earlier. My pride, that classic male barrier, told me not to cry out for help. I was stuck, both literally and emotionally, until I simply stopped fighting. By giving up the struggle, I was able to disentangle myself and make it back to shore. This moment was a powerful, if temporary, lesson: sometimes you have to surrender control to survive.

Men are often taught that showing vulnerability is a weakness. We build walls to protect ourselves, mistaking emotional stoicism for strength. This is one of the most significant barriers preventing men from processing their trauma.

The old-school notion of masculinity dictates that we should be the rock—unmovable, unfazed. But this emotional repression is like being caught in a kelp bed, thrashing around and only getting more entangled. We drown in our own unaddressed emotions, stuffing them away, becoming isolated and angry. The narrative of my life, as I explore in Asshole, was dominated by this cycle of unprocessed pain.

It was my friend Jay Resnick who helped me break this cycle. I grew up in Northern California, and Jay was a Southern California native. Together, we were a couple of Californians who, to outsiders, might have seemed like we had it all. Jay and I were colleagues, and he was the embodiment of a healthy, laid-back masculinity. He was kind, soulful, and unfazed by things that would have rattled others. For years, he gently encouraged me to try surfing. He wasn’t demanding, just consistently offering a hand, a contrast to the coldness I had experienced before. In a world where I expected criticism, Jay offered genuine encouragement. This simple act of friendship was a form of self-love I hadn’t yet learned to practice. His support gave me the courage to sign up for a surfing retreat in Mexico, a decision that felt like a direct rebellion against my own fear.

Learning to surf became a metaphor for processing my emotions. The ocean is unpredictable, and you can’t control it. You have to understand the currents, respect the power of the waves, and learn to move with them, on them, rather than against them. It taught me accountability—I had to take responsibility for my own safety and skill. It demanded self-love in the form of self-care, as I had to learn to protect myself and my body from the ocean’s dangers.

Jay’s encouragement was key. He was a patient mentor, offering supportive high-fives and guiding me to a point where I could find my own community in the water. We discovered a kind of healthy, reciprocal relationship that was entirely new to me—a bond built on trust and mutual support. We saved each other’s lives—me from the trauma of my past by him pushing me into the waves, and me saving him from choking on a piece of hot pork during a barbecue we were hosting backstage at a music festival. In a remote location with no medical assistance, my quick thinking helped dislodge the food, averting a crisis. It was a clear demonstration that healthy masculinity isn’t about being a lone wolf. It’s about being present, accountable, and supportive of others and yourself.

Surfing didn’t just teach me to ride waves; it taught me how to live.

I had already started the work of self-improvement through psychotherapy and yoga, which had begun to crack open the door to a better me. But surfing complemented my yoga and intensified the growth. It was about finding pure joy, something my dysfunctional childhood had robbed me of. If yoga and therapy were the doors that cracked open to a new me, surfing—and Jay—flung it wide open. It showed me that confronting fear isn’t just a challenge; it’s a path to freedom. Healthy masculinity is about acknowledging your fears, processing your emotions, and practicing self-love not as a luxury, but as a necessary act of survival. And sometimes, it takes learning to catch a wave to learn how to live and communicate genuinely, with vulnerability.

You may also enjoy reading Interview: Lewis Howes | Redefining Masculinity, by Kristen Noel.