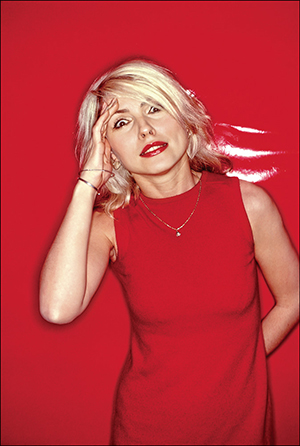

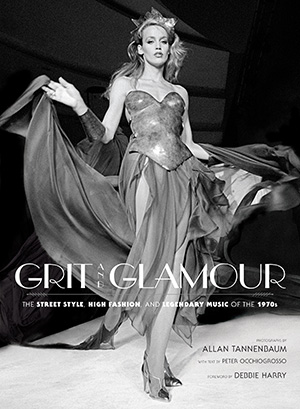

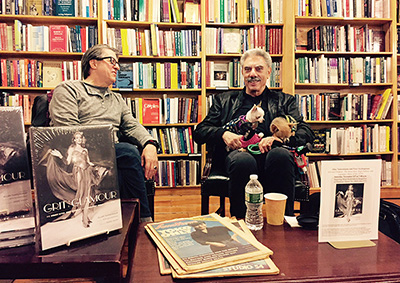

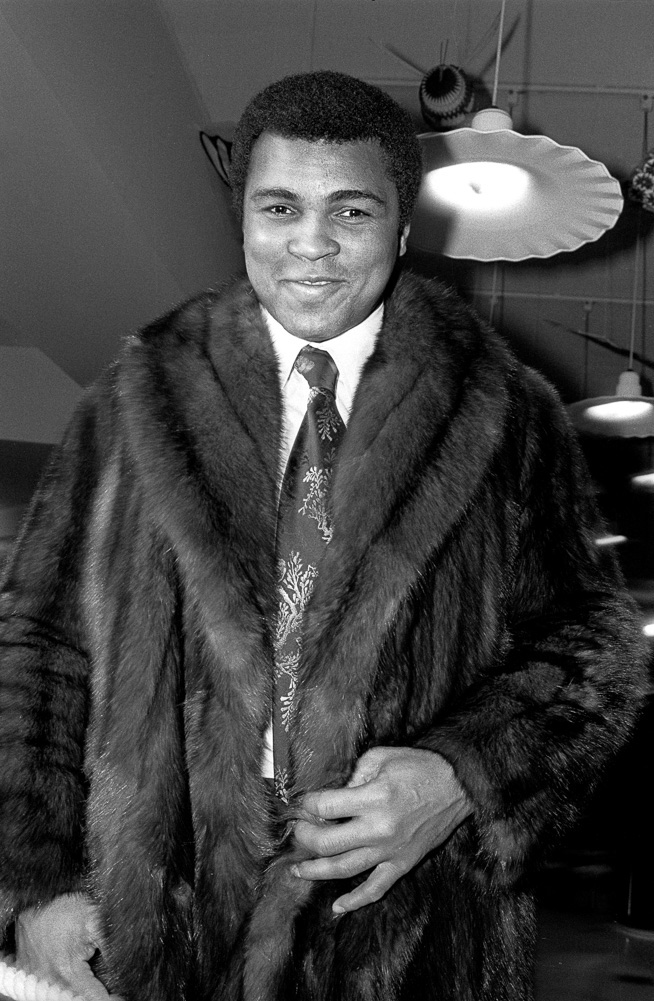

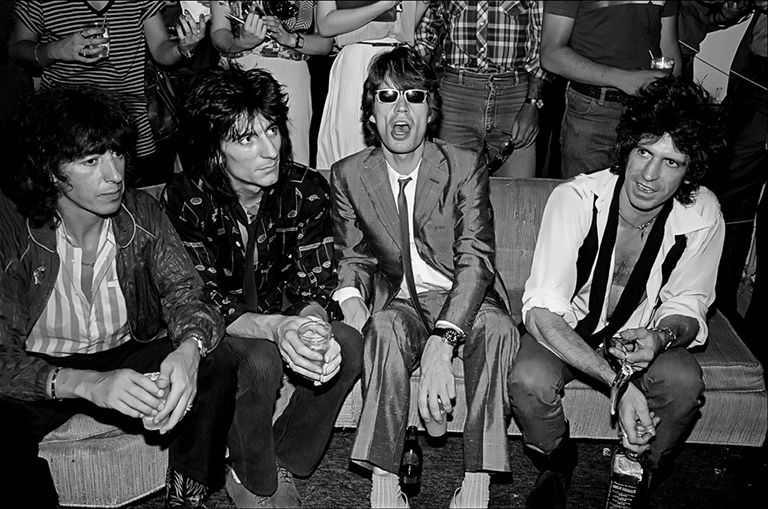

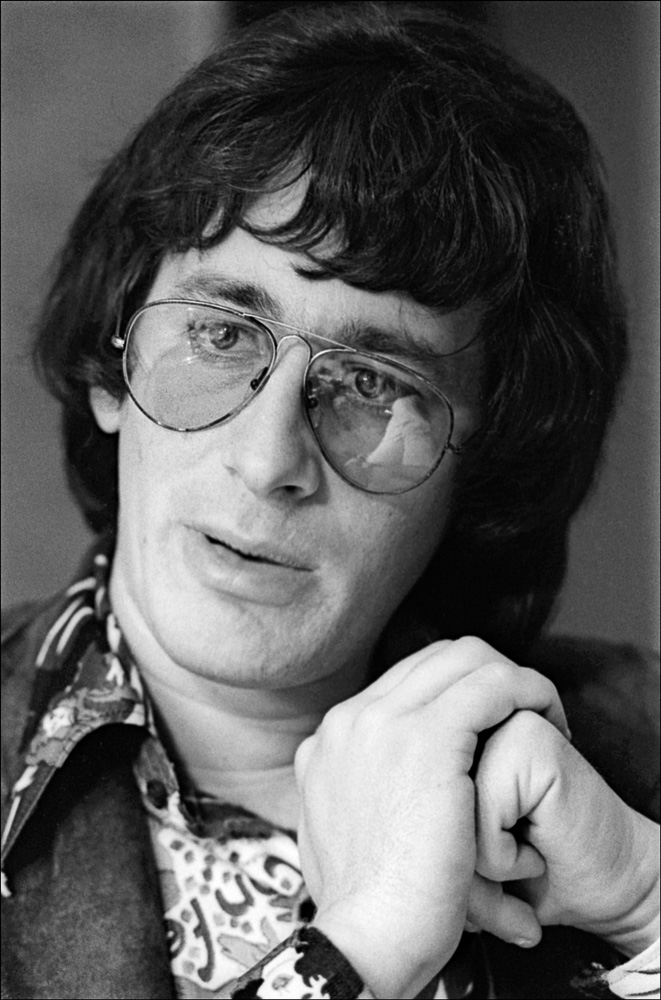

Photographer Allan Tannenbaum’s latest book, Grit & Glamour, showcases the street style, high fashion and icons of the 1970’s

—

Prologue

by Allan Tannenbaum

[Scroll to bottom to view the gallery]

When I first started photographing in the mid-1960s, I had no idea what I wanted to do or where it would take me. San Francisco was a good place to learn, however, with a city rec center where you could develop your film and make prints for a $10 yearly membership. The city itself was photogenic, and with the advent of the hippie scene and inexpensive rock shows there were plenty of visuals.

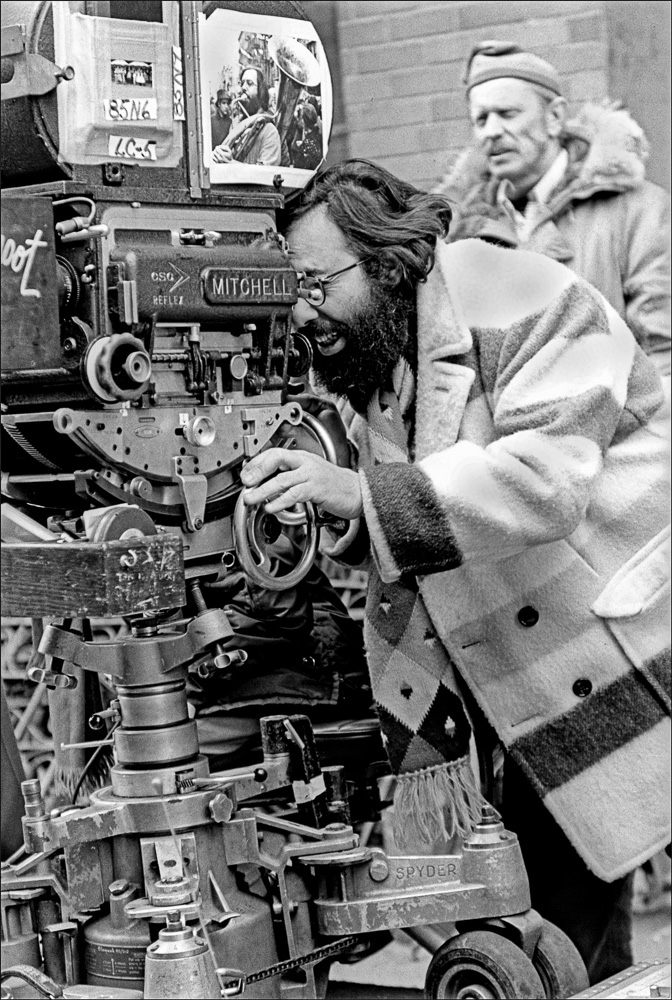

Foreign films were a passion for me, and while finishing my BA in art at Rutgers University, I saw Michelangelo Antonioni’s first English-language film, Blow-Up. I was fascinated with the lifestyle of fashion photographer Thomas, played by the late David Hemmings, and I liked that he did documentary work as well. After I saw the film twice more, the die was cast. This was what I wanted to do. For my graduation I even got a Hasselblad 500C camera, like the one Thomas used in the film.

While studying filmmaking as a graduate student at San Francisco State, I used that Hasselblad and my 35mm camera to take still photographs. The first time I brought my camera to a rock concert was a Jimi Hendrix show at Winterland in 1968. But when I went back to New York, it took me a few years to find photo work, and the job I landed as an assistant in a fashion studio lasted exactly half a day. Not until I became the chief photographer at the Soho Weekly News in 1973 did the universe of New York City open up for me. SoHo was really an art center back then, and the paper covered the art world, the music scene, nightlife, showbiz, politics, and fashion. Soon I got a loft where I could set up a photo studio. The ’70s were a very hedonistic time, and people dressed the part, whether they were on the street or at the latest club.

Annie Flanders (who later founded Details magazine) became our style editor, and she stressed that style and fashion were two different things. One could have lots of style without worrying about up-to-the-minute fashion trends. On a person without style, fashions could look ridiculous.

In my photo coverage, I made sure to notice how people looked in terms of what they wore and the message they were trying to convey with their style and attitude.

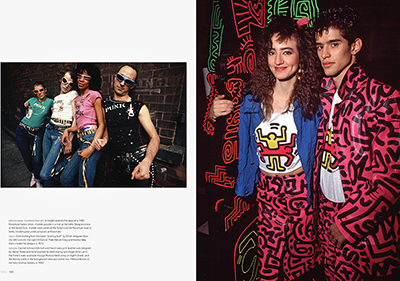

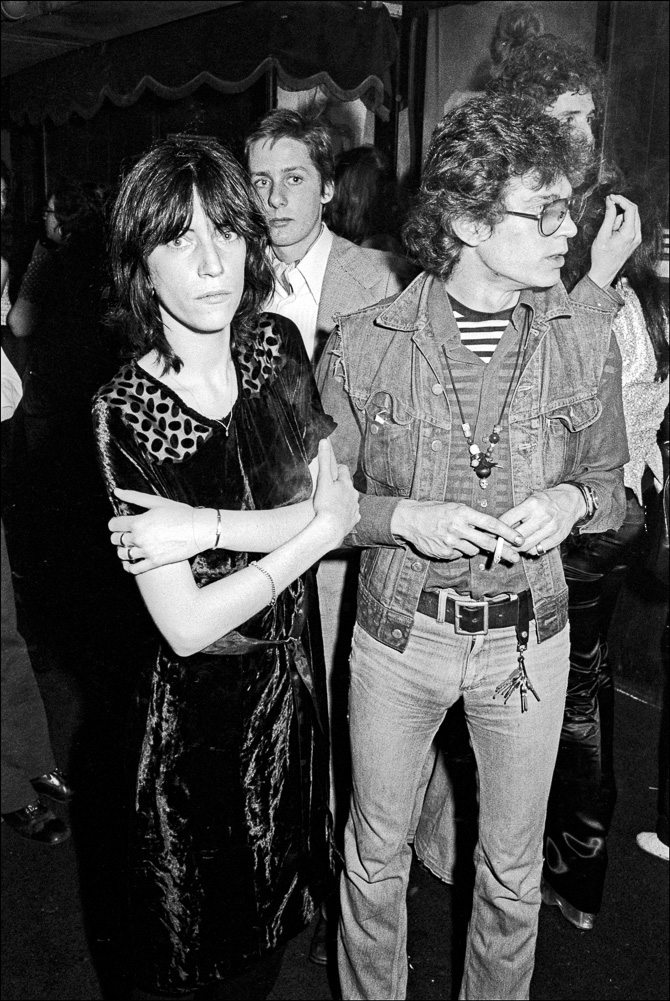

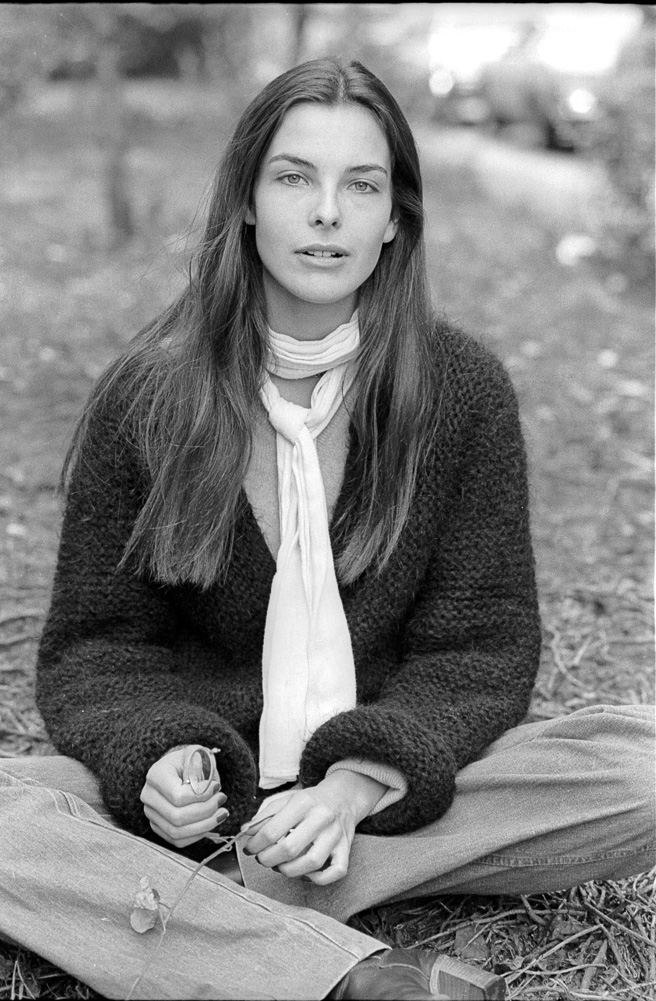

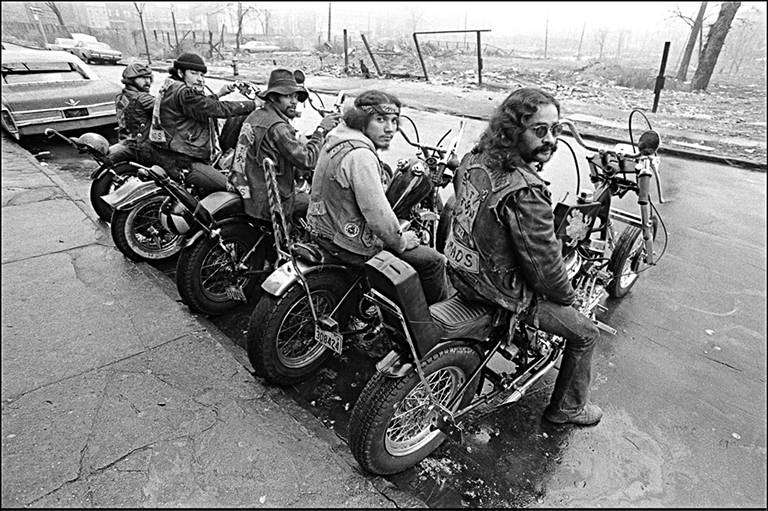

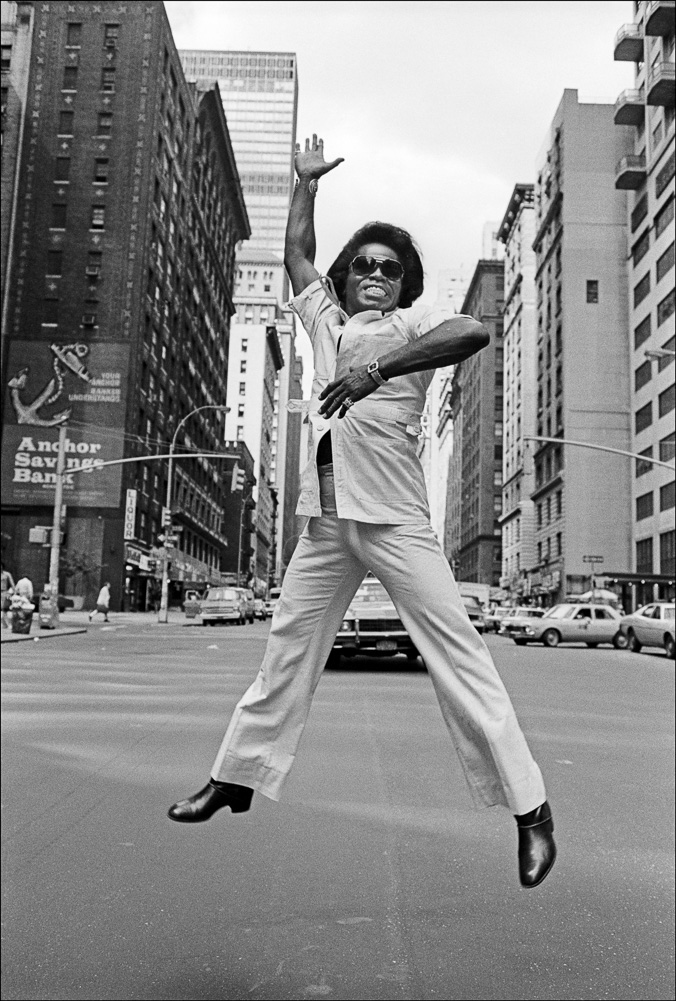

Whether the subject was young Latinos in Central Park, rock bands backstage, or trendies in the clubs, capturing the style of the moment was essential. Looks of the era were eclectic, from nostalgic to modern, but the overriding ethos seemed to be an individualistic notion of style that fit with the ever-changing trends. You can see this in the faux glamour of Studio 54, the funky look of downtown artists and scene-makers at the Mudd Club, and the nascent punk style of CBGB on the Bowery.

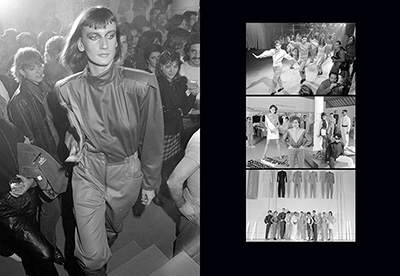

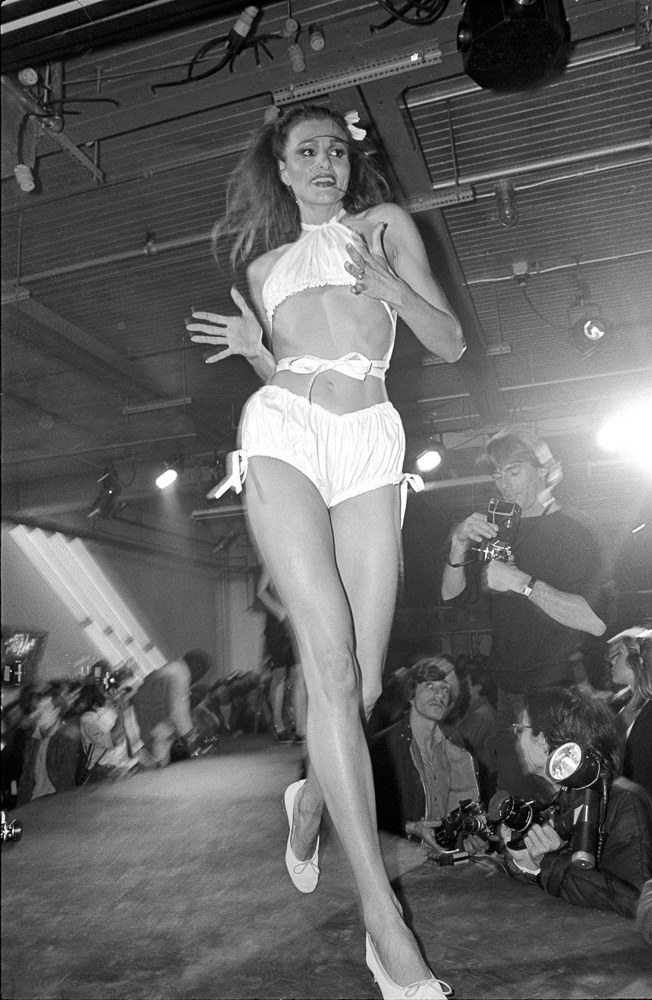

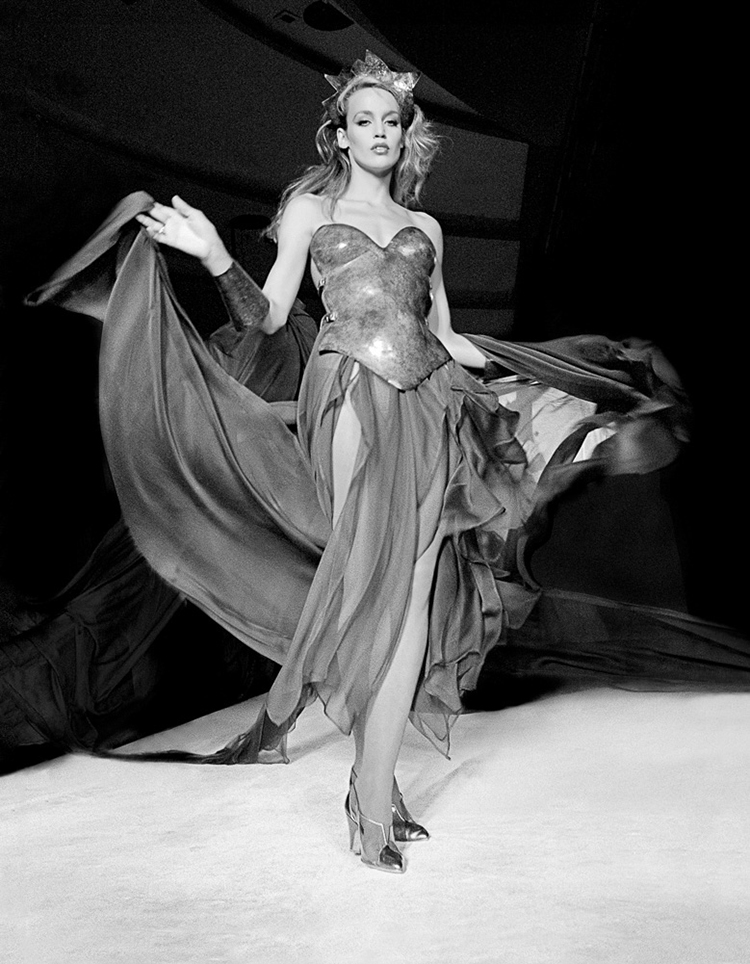

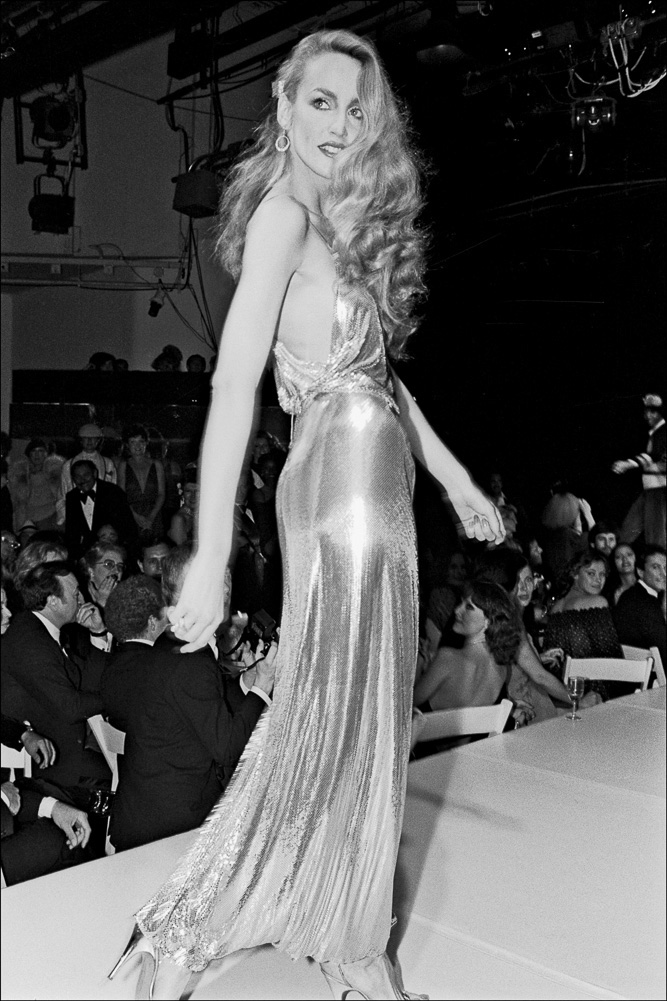

New designers sprang from this fertile ground downtown, with styles and shows that were truly avant-garde. Betsey Johnson was a seminal figure in this new scene, and her clothes and shows had an exuberance that you don’t find today. Fiorucci also had this sense of color and fun, and a designer like Larry LeGaspi was way ahead of his time. The way fashion shows were presented in venues including Studio 54 and Bond’s and even the Mudd Club generated excitement and fun, especially compared to the staid, formulaic shows of today.

Alas, the Soho News folded in March 1982. I had had eight years of Blow-Up. My 1960s bell-bottoms and T-shirts had given way to shiny double-breasted satin jackets, which gave way to skinny mod ties. It was time to move on with my photography, but I had amassed an extensive archive of how the denizens of

New York City presented themselves visually to the world.

The Parallel Style Lines of Grit and Glamour

By Peter Occhiogrosso

The sense of unresolved mystery that fascinated Allan Tannenbaum about the film Blow-Up may have been what led him to eschew the glitzy world of fashion photography for the grittier reality of photojournalism. But truth be told, he was never really game for that kind of work. His first day on the job as an assistant to a fashion photographer, he listened to the man talk about how much money he was making, but he found the work tedious. “‘This isn’t for me,’ I said. And the guy fired me.” Tannenbaum did some work for a wire service, but they complained that he used his wide-angle lens too much. There was always the option of street photography, the general idea being to catch people off guard in ways made famous by the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Garry Winograd. But he never much cared for that approach either.

“I realized that as much as I like to go out in the street and take pictures, it’s not primarily to make art,” Tannenbaum told a class in Advanced Street Photography at Manhattan’s International Center of Photography in March. “The pictures I liked to do were when I had an assignment, when I had a story to do, or when there was an event. And I like to tell the story. It’s pretty much straight-ahead documentary.”

One day in 1973 he stopped to get gas in Brooklyn, but the station was so overcrowded because of the Arab oil embargo that he couldn’t get in. Instead, he jumped up on the roof of his car and shot the whole chaotic scene. Newsweek bought his photo, ran it across the page as the lead, and he had found his calling. Not that it’s always so easy to get those “straight-ahead” shots; you have to have a passion for it.

And sometimes sharp elbows help. I was at the Mudd Club one night in 1981 to see a new wave synth-pop band called Shox Lumania, and the place was packed tighter than that Brooklyn gas station. I had worked my way through the crowd as close as I could get to the minimal stage. The Mudd was famous for having a main floor innocent of chairs, tables, or anywhere to sit, so the audience all pressed together, making it hard to maneuver for a decent view. Suddenly I felt a hand on my shoulder pulling me backwards, and heard a voice say, “Watch out, I’m coming through.” I spun around ready to push back, but the other guy was half a foot taller than me. He also had a familiar face. I recognized Allan, brandishing his camera as he passed me by without comment and made his way to the front of the stage — something I’d been unable to do. But Allan was like that.

He wasn’t being nasty about it; he just needed to get that shot. And he did.

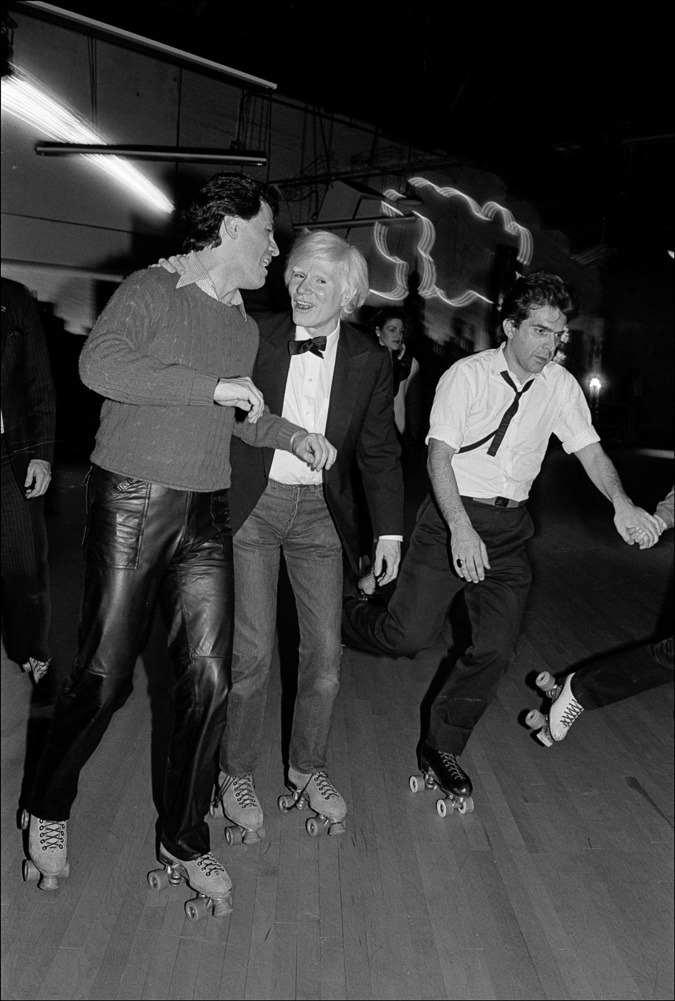

In the 1970s and early ‘80s, when Tannenbaum and I served as photo editor and music editor, respectively, of the Soho Weekly News, we covered much of the same territory — from Max’s and CBGB to Studio 54 and the Roxy, sometimes meeting up at after hours joints like the Mudd Club or Area later that same night (or morning). Grit and Glamour features hundreds of Allan’s color and black and white photographs — a comprehensive archive of pictures that tell the story of two worlds. A thriving indie fashion scene was growing up and flourishing in SoHo and Downtown Manhattan alongside the raunchy, in-your-face ethos of those downtown punk clubs, while in the parallel realm of uptown glitz at Studio 54, the big name couturiers who designed for its patrons were holding sway.

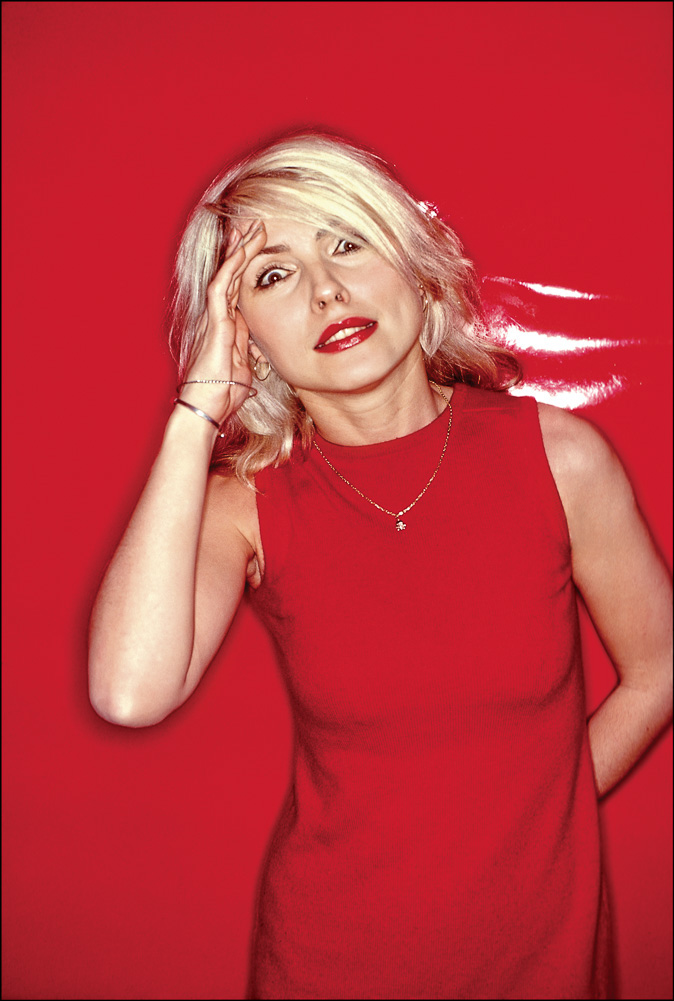

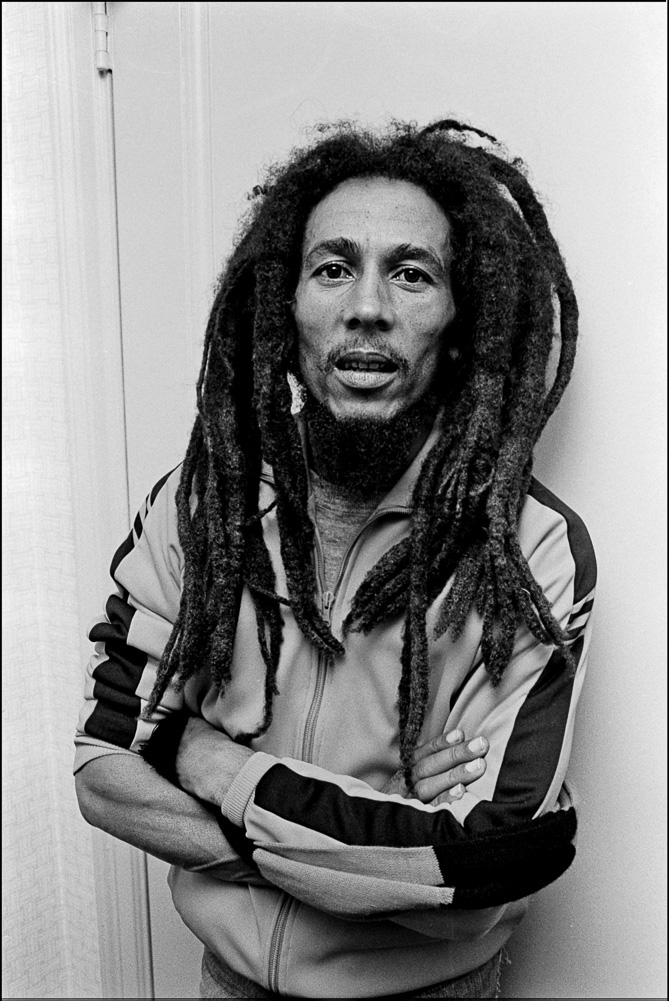

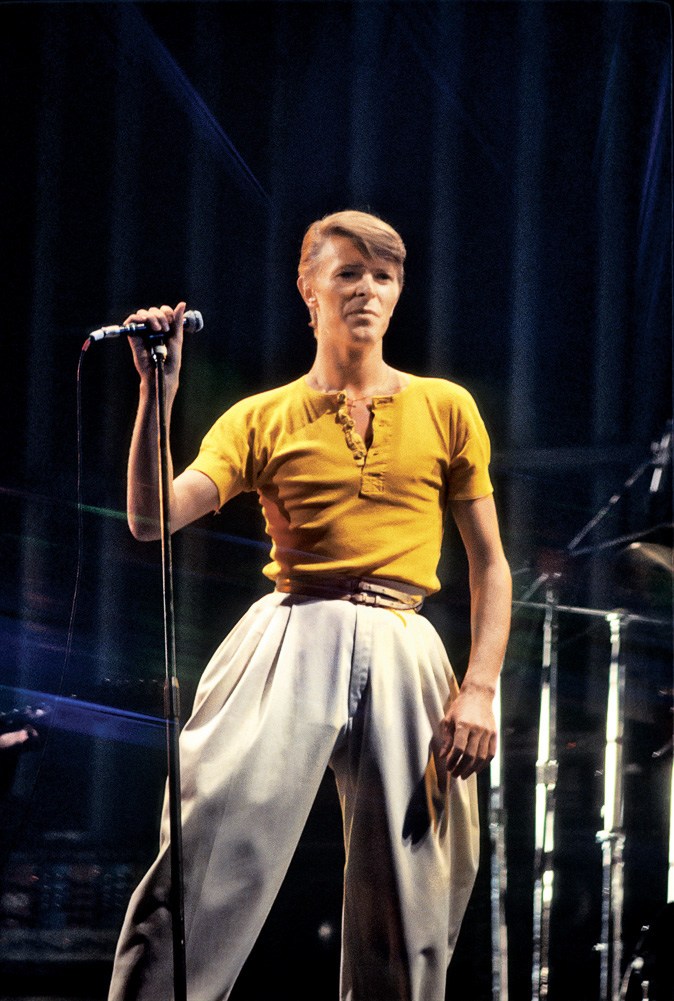

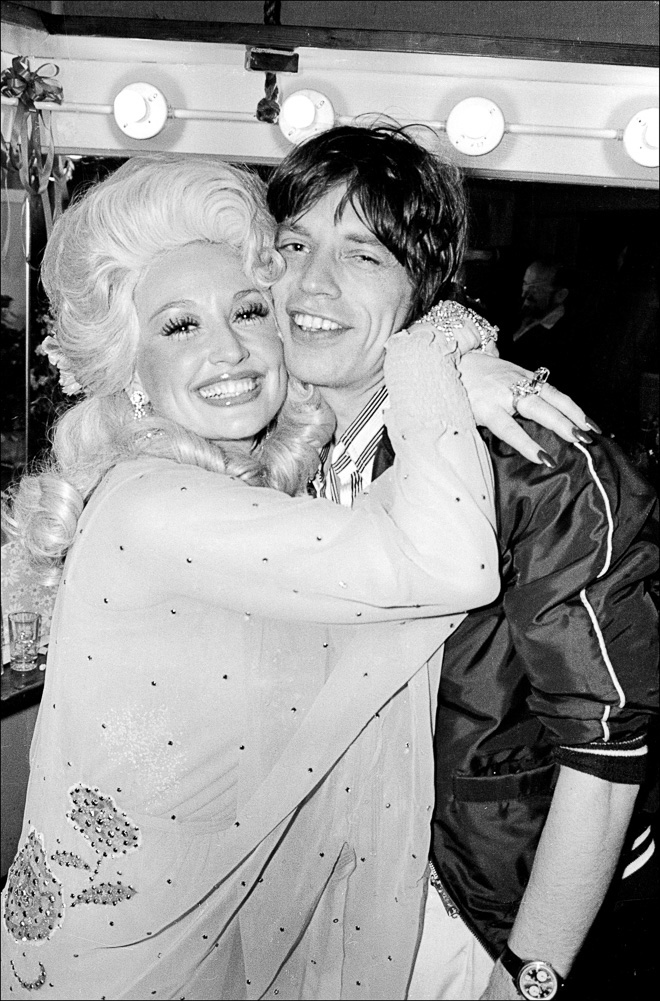

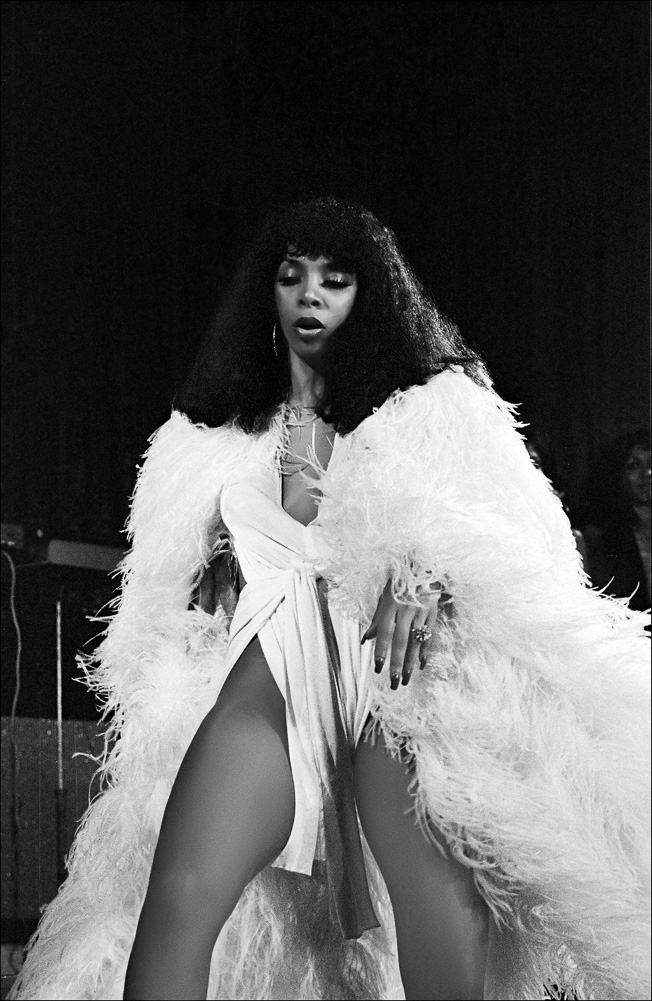

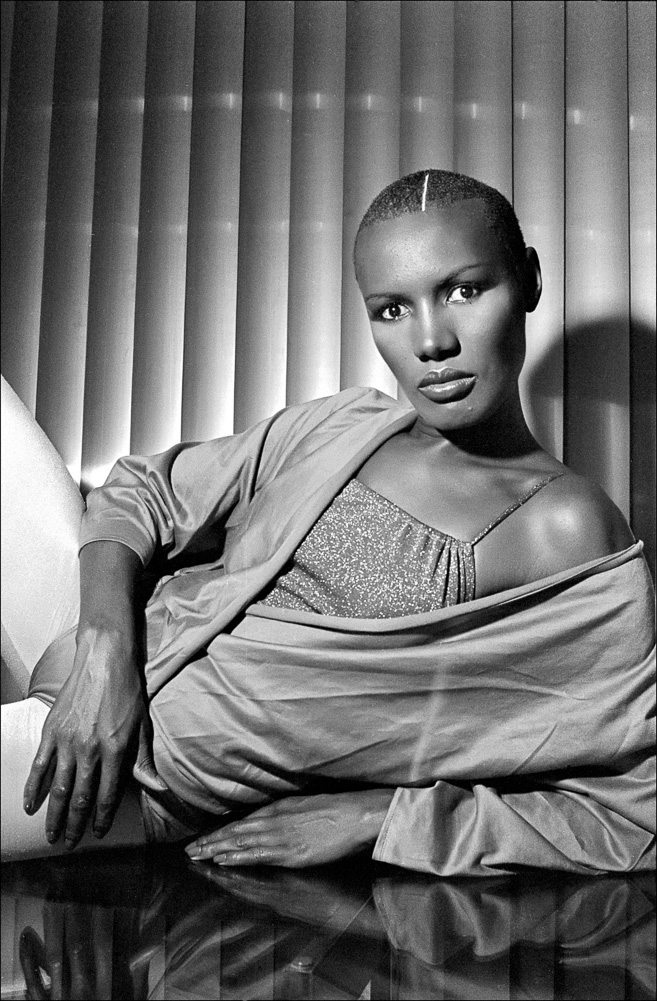

Designers from both worlds also drew on New York’s vibrant, unpredictable street styles in subtle and direct ways that are only now becoming apparent. In the 1970s and early ‘80s, the city was a confluence of diverging styles and looks, of music and nightlife that combined more creative elements in more intriguing ways than perhaps at any time before or since. On a single night during that span, you could hear the whole history of rock and roll, including retro ‘50s sounds, revamped rockabilly, R&B bands, and the blues; the mainstream rock of the Stones and the Who at the Garden; punk outrage and new wave synthesis, from the Plasmatics and Richard Hell to DEVO and Blondie; British imports like the Clash, the Cure, and David Bowie; and disco divas Gloria Gaynor, Donna Summer, and the inimitable Grace Jones. And, in various parts of town, the emerging sounds of hip-hop, rap, and reggae were on display, often by their originators, such as Fab Five Freddy, Bob Marley, and Steel Pulse.

At the same time — often on the same day — you could see the clothing styles that went with all that music. There were Halston and Calvin Klein hanging out at Studio 54 with Bianca, Liz, Andy, and all the usual suspects. Across town the Italian designer Elio Fiorucci opened a store down the block from Bloomingdale’s that became known as the “daytime Studio 54,” with its gold lamé cowboy boots, vinyl stretch jeans, new wave music, and models dancing in the windows.

Meanwhile, independent designers were living and working downtown, outside the reach of the strobe lights and booming sound systems, generating styles that pushed the outside of the fashion envelope until it almost exploded.

Crazed animal prints, skewed geometrics, polka dots, and every kind of stretch fabric were put to stunning use by not only Betsey Johnson, but imaginative innovators like Natasha Adonzio, Valerie Porr, and Isaia Rankin as well. Adonzio was the first designer to hold fashion shows at the Mudd Club, Hurrah, and other music venues. According to Janel Bladow, who wrote about style for the Soho Weekly News, a show by Adonzio or the SoHo Designers was not so much a fashion show as an event, a party, and the more outrageous, the better. “In place of the usual staid catwalk shows,” Bladow says, “designers like Natasha put on performances! The models looked a bit like Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust — tall, thin, red-lipped, with smoky eyes and spiky hair. Her clothes were all skintight, made with clingy, stretchy fabric, lots of edgy short skirts, and tops that sometimes bared the models’ nipples.”

Although I loved the Mudd Club for its danceable music mix and no-frills dance floor, I hadn’t known about the daytime fashion shows until later. Allan, though, was seemingly always on the job. Shooting not just music and nightlife but also fashions, celebrities, and just plain folks. He has a style of taking pictures that is deceptively simple — occasionally candid, but often with the subject looking right at you. If they knew he was taking their picture, fine. If not, he took it anyway. That declarative, documentary style marks his best work. One shot near the end of the book is of a young worker in the Garment District, clad only in sneakers, jeans, and an open denim jacket with cut-off sleeves and no undershirt, pulling a rack of remarkably ordinary-looking women’s coats. Like his outfit, he is all business, and without breaking stride he glares at the camera as if to say, “You think this is easy?”

View the Gallery: Tap any image to enlarge

You may also enjoy reading Jazz & Spirituality | The Mindful Music of Jack DeJohnette by Peter Occhiogrosso