Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

A childhood experience of loss persists many decades later as the author works through complex and even surprising emotions while writing a novel

—

When I was twelve, a boy named Billy from my Sunday school class died when he followed his father into their burning house to try to save possessions. I’d known Billy, though not well, my whole life, and I was profoundly affected. Shock reverberated throughout our church community, but back then, no one sent kids for counseling after such a terrifying event.

Months later, when a neighbor boy arrived home from school and opened his kitchen door, smoke came pouring out. He pounded on our front door, hysterical; his dog was trapped inside his garage. My mom restrained him from going inside his burning house to rescue his pet. It was gut-wrenching waiting for a firefighter to jimmy open the garage door. The dog came running out and a happy reunion ensued.

It was evening by the time the firefighters carried smoldering furniture onto the neighbors’ lawn. I remember all of it sitting there, charred dressers and beds and a little table with a fishbowl, three dead goldfish floating on top. Our neighbors invited us into the house to walk through rooms with blackened walls and ceilings and an unbearable acrid smell.

It seemed to me like a weird coincidence that these two fires had bracketed my sixth-grade year; as an adult, I realize it must have been an exceptionally dry year. But for months after Billy’s death and then again after the fire next door, I had nightmares. Often in them, a fire burned under our driveway. I walked over the hot ground, knowing that any time flames would burst through the concrete and consume us all.

I struggled with complicated feelings about Billy: shock, sadness, fear, and embarrassment about talking about death at all.

I went around thinking, “I know someone who died,” and then felt guilty, like an imposter, as if I were claiming a grief that didn’t belong to me. The real grief belonged to those who’d been close to Billy and his dad.

I was especially puzzled by my embarrassment. Many years later, as a college professor, I saw this same embarrassment in my students—when my dad died, when a student wrote about the death of her twin sister. It was as if the emotions of grief were so profound that people felt awkward, as if the very fact of death somehow laid the survivors bare.

That underground fire felt like a symbol for all the emotions I had suppressed and the experience of adolescence overall, the sense that there was a jumble of feelings about love and friendship and identity and loss smoldering under the surface waiting to burst forth.

But the fire of my dreams was also about those literal fires that impressed on me how ephemeral our lives are, how temporary are even the things we think of as permanent like our homes and loved ones.

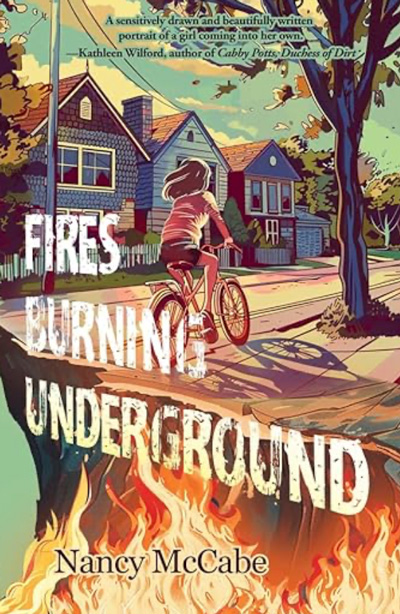

Over the years, fires continued to haunt my stories, starting with one I wrote in high school. A novel I worked on for many years beginning in the early 90s prominently featured a fire. Then, around 2006, I started writing the story that became Fires Burning Underground.

In the novel, on the brink of her twelfth birthday, Anny experiences similar intense and sometimes puzzling feelings at the loss of a Sunday school classmate in a fire. Sometimes she’s convinced that the boy who died is haunting her. His presence, whether literal or metaphorical—I left that open-ended—helps her to come to terms with her mix of emotions. The book, like that year of my life, is framed by fires: at the beginning, one resembling the fire that killed Billy; at the end, a fire in her neighborhood. Anny has to face her terror during that second fire and prevent her childhood friend Ella from going into a burning house to save her dog. In my story, that second fire helps Anny to come to terms with the first.

It’s a bit startling to realize how often I’ve written about this theme. The fact that I’ve continued to return to it reminds me of how significant those early experiences of death can be when we haven’t yet learned what feelings to expect or how to process them. I wanted to write honestly about Anny’s reaction, hoping that doing so in a book that’s also about friendship, imagination, humor and identity, will also reassure young readers that complicated feelings about loss are normal and that over time, we find ways to come to terms with them.

You may also enjoy reading Becoming Myself: Making Peace with a Traumatic Childhood, by Roberta Kuriloff.