Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

When a young boy loses is mother, his relationship to his father, himself and his life is forever changed

—

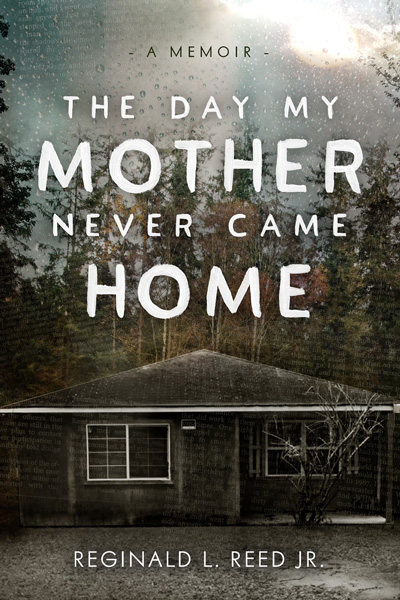

On Aug. 23, 1987, 26-year-old Selonia Reed was found dead in the parking lot of a gas station in Hammond, Louisiana. Nearly 40 years after her death, her husband Reginald Reed was sentenced to life in prison for her murder. But that’s far from the entire story. With unyielding candor, Selonia’s son Reginald L. Reed Jr. courageously navigates the trauma of his mother’s murder and the subsequent arrest and conviction of his father in his debut memoir, The Day My Mother Never Came Home (May 21, 2024).

Below is an excerpt from the book.

As I got to be a bit older—ten to twelve—my father began leaving me home alone when he went to work at night. It was never for long periods of time, and I was old enough to take care of myself. He knew that I would be perfectly fine, otherwise he would never have left me alone. My father always made sure I was covered, and I am sure that he also gave a heads-up to our neighbor Ms. Dorothy to keep an eye on me as well.

When he was gone, I would do normal adolescent boy things, like play video games, and eat snacks. I was never allowed to leave the house when he was gone at night. This was a set boundary that I did not dare cross. Truth be told, this was not a boundary that I even cared to challenge. I didn’t love being home alone, especially at night, so there was no way I was going to leave the safety of our house.

It was around this time that my father and I began what I call our silent exchanges. A lot went unspoken between us during the first few years after my mother’s death, but there was an understanding between us. We did not have to talk through much to understand one another. It was just our way. Looking back, I wish we had both said more out loud. We were both doing our best to survive, and long conversations about our feelings did not fit into our mode of survival.

Something that I would do almost nightly when my father was gone was page him. There were no cell phones back then, so the easiest and fastest way to get in touch with him was by paging him. I would wait until later into the night, typically when I would start to get anxious and nervous about whether he was going to come home. Most young boys wouldn’t worry so much about this. They may call if they were scared or hearing noises. It was different for me. I worried about whether he would come home. I feared the absolute worst possible scenario.

I had reason to worry. If my mother could go out and never come home, surely this could just as easily happen to my father, right?

Statistically, this would be highly improbable; but my mind and heart didn’t care about statistics and probability. To me, it was a very real possibility that one night, he just wouldn’t come home. Most kids do not sit around thinking about their parent dying, or just never coming home. Most kids at this age are busy being kids. They are self-absorbed and do not typically think of much outside of themselves. That is a normal childhood. On those nights when my father was gone, I should have been busy being a kid.

I would beep my father, and then wait anxiously for him to call me back. The phone would ring…

“Hello”

“Lil’ Reggie, it’s me…is everything alright?”

“Yeah, everything’s fine. I was just calling to see if you could bring me home an Icee.”

“Okay, yeah. I’ll bring you home an Icee, son.”

We would end our short call and I would breathe a sigh of relief. My father was okay, and he was coming home.

He never brought me an Icee.

Those calls were never about the Icee, and we both knew it. Some nights it was an Icee, or a burger and fries, and some nights it was a pack of gum from the corner store. He always said, “Okay, Lil’ Reggie, okay.” But, he never came home with any of my requests. He knew my hidden request was for him to simply come home.

Fear was a big part of my childhood.

Though it was not visible and overbearing, I still lived a lot of my childhood in fear. I always feared that one day my dad just wouldn’t come home; that either something terrible would happen to him, or that one day he would decide that raising me as a single father along with the weight of loss and his own grief was too much to bear. I was always waiting for the other shoe to drop. Surely it would, right? One day it would all come crashing down again, right?

The worst possible thing had already happened to me, but I was sure the other shoe would drop at any moment. This is the thinking of a child who has been through trauma. I lived in constant fear. This changes a kid; steals his innocence. My father and I never spoke about the nights I paged him. It was one of our silent exchanges; just another part of how we lived our lives. We never spoke about our fears out loud, but I am sure he had his own worst-case scenario sitting in the back of his mind. I am sure he lived a lot like me, waiting for the other shoe to drop.

Neither of us had the emotional language to express what we were going through, or how we were feeling, so there was no reason to talk about it. He knew very well that when I paged him, I was calling to check on him. My page was the silent cue for him to get on home as soon as he could. Those calls told him that I had been alone long enough, and I needed him to come home.

And he always did. I would hear his car pull up in the carport and breathe a deep sigh of relief.

He was home. All was right with the world in that moment.

If I am being totally honest, I still do this routine of checking in when my wife is out, or away from home. It was more pronounced early in our dating life and within the first few years of marriage. I never asked her for an Icee or a pack of gum, but I would ask where she was, and what time she planned to head home. I suppose this is part habit and part trauma response. I am fiercely protective of my family, so those calls are me making sure that everyone is okay at all times. As I write the words everyone is okay at all times, I realize what a heavy burden this is for someone to carry. Yet, I shoulder it. I don’t consciously feel the weight of it, it is simply something that I do, an extension of survival mode.

I don’t know if I will ever stop making check-in calls, or if I will ever trust that everyone is okay. I wonder how this will look like as my son grows older. I wonder if my fear and anxiety will smother him. I know that most parents deal with this, so circumstances dictate that I will struggle more than the average father. As my son gets older and gains more independence, I will have to decide if I am okay existing within this sphere of anxiety, or if I want to live trusting that he will be okay.

It is a constant struggle to decide what parts of my past to leave behind, and which of them to carry forward into my present life.

Sometimes I don’t even realize that I am operating out of fear, or that I live my life in survival mode. Sometimes it takes someone from the outside looking in to help me recognize my coping mechanisms and survival behaviors. I don’t want to raise my son to spend his life in survival mode. I want him to live a limitless and abundant life without fear, thriving rather than merely surviving.

I realize that through my process of self-reflection and self-awareness, that I must change in order to build a different life for my family—for my son. How does one do such a thing? How does one change something that is so ingrained in their subconscious? I do not yet have the answers, but asking the questions and writing this book are both huge steps for me. I am taking baby steps, but I am walking. Self-transformation is difficult. It is a slow process of unlearning old habits and behaviors. It requires rewriting stories that we have told ourselves for years, even decades. The tapes we play on repeat within our heads need to be paused, and we must record new stories.

For decades my tapes have told me that the world is unsafe. They instill fear and anxiety on an endless loop from which there there is no escape. In some instances, their stories keep me and others safe. It is good to be aware as you move through the world, attuned to things around you that may cause harm. However, for those who have experienced trauma, there is no distinction between safety and survival.

The mind of a trauma survivor interprets everything as unsafe.

The fight or flight response kicks in and we lose our ability to think rationally through our circumstances. This pattern of thought and behavior elicits a great deal of avoidance. It is easier to avoid situations than to fight through them.

Avoidance is a coping mechanism, another survival tool in the already crowded tool belt. It is easier to avoid the thing that may cause us discomfort or pain, rather than take the leap and hope for the best. It is easier for me to not put myself out there than it is to take a chance and see what happens. Avoidance is one of my favorite tools. It keeps me safe. It keeps my family safe. I stay in control (another tool in my belt), but I am beginning to realize that this is no way to live. While the boundaries I set and the walls I build may keep me and my family safe, they also keep us from fully experiencing the abundance of joy that life can bring.

I am sick of boundaries and walls. I am tired of the limitations I place on my own life and the lives of my family. I want to live fully and unafraid. I want the peace and confidence of knowing that no matter what happens everyone will be okay.

My spirit is stirring as I write this because I know that an abundant life is just within my grasp. I have done the work, digging up the old thinking and identifying the problem. Now I must do the work on rewiring my thinking. There is a thrill to it because I feel hope; I see the possibility of a better way of living. I can imagine a feeling of peace and the absence of fear, and I long for it.

I am claiming this new life in advance. I see the light at the end of the tunnel. It is bright, and draws me in. And so, I begin. One foot in front of the other. Every single day I will decide that today, I will look for the light. I will move away from fear and toward the bright light of peace and joy.

You may also enjoy reading Reclaiming Freedom: Rising from the Ashes of Trauma, Neglect and Abuse, by Penny Lane.