Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

One woman explores her calling to become a therapist — was it rooted in the trauma or the values of her WWII-era childhood?

—

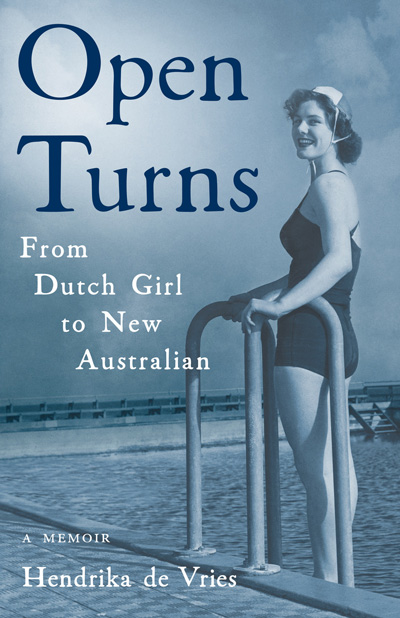

Readers of my stories of brutality and hunger that I experienced as a little girl in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, and my struggle for identity and belonging as an immigrant teenage swimmer in 1950s Australia, often say, “No wonder you became a therapist.”

It’s true that those of us who have experienced childhood trauma and found healing in counseling or therapy often choose a career in psychology to help others.

But when I look back on the events that set me on that path, I wonder if I was destined to become a therapist long before I chose it, and that my family’s response to the events may have been more central to that choice than the trauma itself.

I was just six years old when I learned that helping others whose lives were threatened is simply what you did, even at the risk of losing your own.

Amid the horrors of the war, after my father was deported to a POW labor-camp in Germany, my mother joined the Resistance and hid a Jewish girl in our home. Friends in the Resistance came to listen to the forbidden BBC radio broadcasts that gave them the strength to continue the fight. I saw that it took caring, connecting and courage to make the world a better place for everyone, including those deemed inferior or other.

My mother believed in the power of dreams, which she and my grandmother said were of Divine origin and sent to guide us. Dreams were shared and discussed in the context of all daily events, even when my grandmother’s home was bombed and she escaped with only her life, or after Nazis held a gun to my mother’s head, or starvation threatened to kill us both. When told that my father was dead, she insisted he was alive and would return home, because she dreamt it. He did. No wonder that years later, long before I thought of therapy as a career, I was drawn to the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung’s autobiographical book Memories, Dreams, Reflections with its childhood recollections and symbolic language of dreams.

If my mother taught me about courage, caring, and the power of dreams, my father taught me about the healing magic of awe and imagination.

I was age 5, when he helped me imagine a small toy dog could represent a protective wolf (it led to the title of my first memoir) and connected me to my own inner strength. When I was 13, confused and adrift in a new land, he took me for a walk in the Australian Bush, where he helped me hear the voice of the ancient land in the deep dark silence of the night. It would be many years before I learned about Aboriginal soul-retrieval rituals, but the experience planted the seed that would one day lead to my exploring indigenous and spiritual healing practices.

Neither of my parents tolerated expressions of victimhood, even during the most brutal and difficult times. Like most immigrants I learned that hardships were transformed into lessons of resilience and hope. We were survivors and letting trauma define you made you helpless. It’s not surprising that decades later I felt a kinship with psychologist Robert Jay Lifton, whose powerful work on resilience in survivors of the Holocaust and Hiroshima warned against thinking of themselves as “incapacitated victims”.

I was fortunate to be a powerful swimmer. My parents were both athletic; my mother having been a champion racewalker, and my dad a strong swimmer. They taught me to be an athlete at life: live with intention, discipline and commitment, and believe in yourself.

When I had established myself as a licensed therapist, I recalled a pivotal event. I was 17 years old. Polio had swept the world and left many survivors in Australia with paralyzed limbs. I was on a team of experienced swimmers to support young survivors in an experimental aquatic treatment program. The hope was that water therapy might restore some mobility and help regain a feeling of confidence and strength in their bodies. As they were lifted out of their wheelchairs into the swimming pool, I was assigned to a little guy named Mike. He was about 8 years old. I witnessed the determination on this young boy’s face, saw him pull his arms with all his strength to drag his lifeless legs along as I guided him. When he traversed the width of the pool with a triumphant grin and told me he was “a shark,” I felt such joy, it was for a moment as if all the Light and Love in the universe had just entered the pool. I suddenly knew that I wanted to spend my life helping people find their own strength.

As so often happens to hints that come before we are ready, the memory went dormant. But many years later seated with clients, I would remember it whenever they accessed their own strength, their light, or inner champion. And I would re-experience that joy and privilege of being present to that healing power that unites us all.

“The future enters into us, in order to transform itself in us, long before it happens,” the poet Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote.

In essence, my decision to become a therapist was in some deep way born from a confluence of early threads: a little boy’s determination, my mother’s and others’ wartime caring and courage, the power of dreams and imagination, the experience of awe in a strange land, and a belief that everyone has an innate strength waiting to be uncovered. It was a calling shaped by my history — and my soul had already set its course long before I consciously recognized it or knew it was my destiny.

You may also enjoy reading The Drivers, by Tracy Christian.