Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

While appearing to have it all, one woman finds herself feeling empty in mid-life…until an unexpected meeting changes her life forever

—

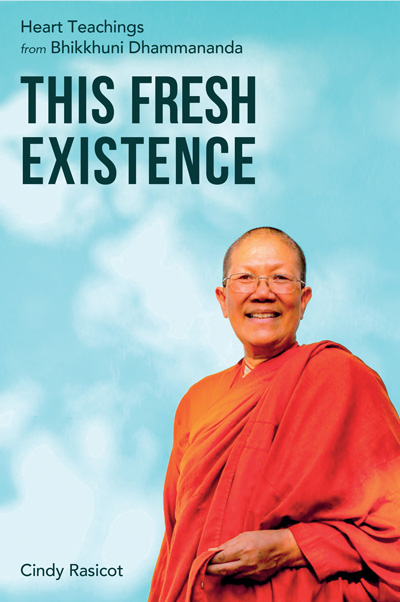

[This essay includes excerpts from This Fresh Existence: Heart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhammananda (Windhorse Publications, April, 2024)]

I have always been a spiritual seeker. At age four, I asked my brother, who was five at the time, “Where is God?” He answered. “Everywhere.” Puzzled, I searched through the bushes but never found what I was looking for. I kept my brother’s words in my heart and figured I’d find the answer some day. That answer came in mid-life through a serendipitous encounter with a Thai Buddhist nun, Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, who led my on a spiritual journey from which there was no turning back.

The year was 2005. My husband, thirteen-year-old son, and I had just relocated from our suburban home in Northern California to Bangkok for my husband’s job. Even though I was fifty-four years old when I met Venerable Dhammananda, I was not yet my own person. I did not have agency, direction, or backbone. Although excited to be living in Thailand, I was not particularly happy. I was in survival mode.

A wife and mother first and foremost, I did not question my marriage of twenty years, and was not passionate about my career working for non-profit organizations. To the outside observer, I was a successful ex-pat mom, living a life of privilege in Bangkok, and while that was true, I was suffering from a deep sense of insecurity, as if I were missing an essential part of myself. I wanted to feel passionate about life, confident, and connected.

Perhaps that is why, soon after we arrived, I signed up for a women’s conference and attended an afternoon workshop entitled “Faith, Feminism, and the Power of Love.” That is where I first encountered Venerable Dhammananda, Thailand’s first fully ordained Theravada Buddhist nun. She was a tall, slender Thai woman dressed in saffron robes and flip-flops. Her head was a fuzzy crown of black shaven hair, and she wore thin gold wire-rimmed glasses. She possessed a quiet confidence as she spoke, and I still recall her words:

“We cannot solve anything with anger. Anger does not lead us anywhere. It is much harder to practice loving kindness and compassion. That is the goal of Buddhism.”

I felt chills as if she were speaking directly to me. I had struggled with anger all my life and intuitively knew I was blocked somehow, stuck in a negative cycle of resentment, sadness, and fear. I had never encountered anyone, particularly a Buddhist woman and a feminist, who spoke so quietly and radiated such a soft light. Her kindness was contagious, and I believe what drew me to her was my absolute faith in the power of her love.

Cindy and Venerable Dhammananda at her Temple in 2006

That was how our relationship began, and during the next three years I lived in Thailand, I became a Buddhist, and Venerable Dhammananda became my spiritual advisor, mentor, and teacher. The funny thing is that I was not born Buddhist; I was raised Jewish. But something about Venerable Dhammananda’s message transcended religious differences. Her words about loving kindness touched me to the core.

In the twenty years I have known Venerable Dhammananda, I have learned that being in her healing presence is a gift. There is something intensely compelling yet comforting about every word she speaks. When we talk, she gives me her full attention. Such is the power of her awareness; she is completely anchored in the here and now. While we are together the outside world drops away. There is no “Cindy,” there is no “Venerable Dhammananda,” there is only our connection. As she put it, “Not being Cindy, not being will, just be.” When we experience being, we are one. We leave aside individuality and separation.

Venerable Dhammananda says, “To be anchored in the present is a mental exercise.” She makes this look deceptively easy, but the truth is, it takes years of mental training and meditation practice to be fully present.

When I sit with her, she transmits to me, as if by osmosis, her personal teachings. It is an energetic exchange, one which I sense with my whole being, like warm sunlight streaming in, and an experience I cherish. However, our relationship has not always been harmonious. We have had our challenges.

One time in January of 2020, our relationship was seriously tested. I was visiting her temple shortly before my first book — a memoir called Finding Venerable Mothr — was published. I had given Venerable Dhammananda an advanced reader’s copy to review and was anxiously awaiting her feedback. I was not convinced she would like it, given the whole idea of memoir — writing about oneself — is so self-involved. This focus on the personal narrative ran counter to Buddhism which involves letting go of the ego and grasping. Even so, I hoped for the best and wanted her praise above all else.

It was mid-afternoon, and we had planned to meet at 3:00 pm in her favorite spot, a shaded area located underneath the dormitory, protected by a roof overhead. I sat and waited at a small, stone table. The air was still and hot. I glanced down at my watch, 3:05 pm, the waiting was excruciating.

Within minutes she drove up on her maroon scooter she now uses as she gets older, comfortably perched as she pulled into her familiar parking space alongside the table. As she stepped off the bike, she carried a copy of my book in her hand. I took a deep breath as she began the conversation. “So, I have read your book. There are a few changes I want to make. You use the word ‘pray’ a lot, but in Buddhism we do not pray, we chant. Like here,” she pointed to a page, “This passage should read, ‘We pressed our palms together, bowed, and knelt as the nuns chanted a blessing’ — rather than prayed — ‘for us.’”

I was searching for signs of reaction in her face, but her expression remained neutral. What is she thinking? Does she like the book? She continued flipping through the pages showing me where she had marked other changes.

This had not been a particularly easy visit. I sensed Venerable was frustrated with me, but I was not sure why. Then, looking directly at me, she said, “You remember the three brothers, greed, anger, and delusion? We are talking about grasping. Grasping for I, me, my, mine. You say my Venerable Mother, my teacher — this is grasping. When you let go of this grasping, Bodhicitta — enlightened mind — can blossom.”

I was shocked and hurt by her response. I thought I had written a beautiful tribute to her, and she saw it as an example of my possessiveness. After our conversation I spent a quiet afternoon, feeling miserable. Later, all the nuns gathered as usual for evening chanting and Venerable Dhammananda’s dharma talk.

Dhammananda shared a story about a nun who realized she was pregnant. The Buddha understood that this woman had been married before and probably had not realized she was pregnant until she was already ordained. The question was whether she could remain in robes. Ultimately, it was decided that the woman would be allowed to remain ordained, keep her son for one year, and then relinquish the child for adoption.

The essence of the story was that the mother could not stop grieving for her son and wanted to spend time with him. She finally saw him again at the age of twenty-one. He was also ordained and was very harsh with her. The mother felt bad, but she was unable to stop clinging to him. Eventually the woman was able to stop clinging, let go of her craving, and became enlightened. That was Venerable Dhammananda’s message to me. She felt I was too possessive of her, my Venerable Dhammananda, clinging to her and idolizing her in a way that was unhealthy. She was sending me a message to let go of my attachment to her and allow for a spaciousness to grow in our relationship.

The next day we met again, and I decided to bring up the subject of grasping. She drove up on her motor scooter and parked. Once she had a chance to get settled, I asked her directly, “Yesterday you were saying I am grasping at you? Do you feel that way?”

“Yes. I feel that when I read your book.”

“Do you think I am placing you on a pedestal?”

“Maybe. On the positive side you were saying ‘Venerable Mother’ helped you heal your suffering. But when you go overboard people might feel like that ‘Oh, she is my teacher, my venerable mother;’ it’s too much. You need to tone it down, so people get that the learning is not personal, but universal.”

I took a deep breath and processed what she was saying. “So, are you telling me I need to let go of grasping to allow my mind to be enlightened?”

“Yes,” she said. “When you hold onto something so tight,” she gripped a water bottle to demonstrate, “it is not comfortable. When you simply touch it, then it feels natural. Allow freedom of the other party.”

I was beginning to understand what she was saying.

For years, I tried to control our relationship by constantly seeking her approval. I was grateful when she showed me attention but was also jealous when she singled out others for praise. My possessiveness was a kind of adulation, but I was suffocating her, although that was not my intention.

I thought about this conversation for months afterward, and about how, in all the years I have known Venerable, she keeps coming back to one theme: Letting go of I, me, my, mine. I asked her why this was so important to her.

She leaned forward with a look of earnest concern and said, “That is the core message of the Buddha. All the suffering and problems that we have are nothing but the clinging on to I, me, my, mine. If we want to experience true freedom, we need to be able to let go of the self, which from the very beginning is not there.”

Three years later and without prompting from me, she brought up our earlier conversation and said, “And there was a time you were clinging to me as your teacher. You had so much faith in me, but I felt it was too much. I was afraid I would hurt your feelings by telling you.”

I was surprised to hear this and reassured her I appreciated her feedback. Her honesty had helped me look at our relationship and where I needed to let go. If she had not challenged me in the way she did that day, I would have remained stuck in unhealthy behaviors. She helped me to understand a core Buddhist teaching: clinging to oneself causes suffering. I am forever grateful.

The most profound experiences I have had with Venerable Dhammananda have been the two times I received temporary ordination, once in 2014, and again in 2022. Venerable Dhammananda offers temporary ordination at her temple twice a year. During the novice ordination women come to live at the temple for nine days, take the ten precepts, study the spiritual teachings of Buddhism, shave their heads, wear the robes, and practice meditation in hopes of improving their overall peace and contentment once they return to their normal lives. The opportunity is open to Thai and non-Thai citizens alike. At the 2022 ordination there were twenty-one candidates seeking ordination. I was the eldest participant at seventy-one and the only non-Thai speaker.

The highlight of my most recent ordination experience in December of 2022 happened when the entire group went on a dawn alms round, called bindabat in Thai. This practice dates back to the Buddha’s time and benefits both the ordained monks and the laity. Monks depend on the local people for food, and in return the locals receive spiritual guidance from them.

Cindy accepting alms during temporary ordination, December 2022

People in the community wake early to cook rice and other foods for the ordained women. By offering food, they are practicing generosity and with these acts of kindness they are generating good karma. Many Thais believe in karma and rebirth and that the actions they perform in their current life will have an effect on their next life. By giving alms, the locals are building good karma for their future.

The monastic women at Wat Songdhammakalyani go on alms round between 6 and 7 a.m. every Sunday and on Buddhist holy days. The day our group went out for alms was a Sunday. We lined up according to height and exited the temple gates in partial darkness. As we turned off the main highway to a side street, word spread fast among the local community that a procession of twenty-seven women, novices and fully ordained bhikkhunis, carrying alms bowls, was approaching. Excited onlookers ran to catch a glimpse of us and then darted back inside to grab rice, water, packages of food — whatever they could get their hands on — to offer alms. It was kind of like a flash mob, a wave of people that swelled and gained momentum as we made our way down the street. People were overjoyed to see us, and we received almost four times more food than we normally collected. The cart carrying donations was overflowing. The people’s acceptance was heart-warming.

Cindy being shaven for her temporary ordination, December 2022

I would sum up cumulative years knowing Venerable Dhammananda in one word: initiation. For me the word ‘initiation’ means a new beginning and marks my transformation into a new way of life. Sharon Salzberg, world-renowned mindfulness and loving kindness teacher has a saying “We can always begin again.” At my age, this is my mantra.

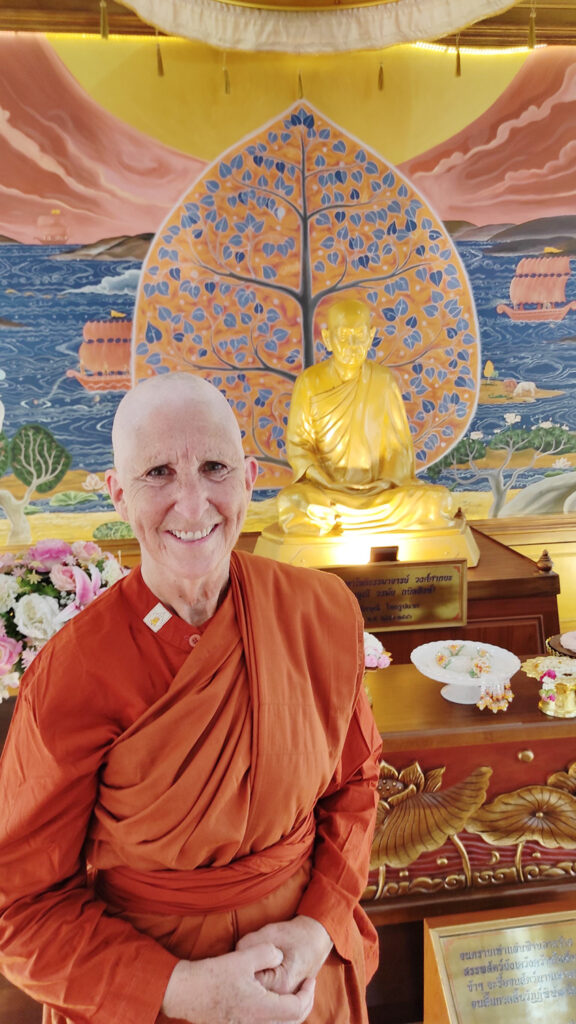

Cindy and Venerable Dhammananda in September 2023

Whenever I visit Venerable Dhammananda it is as if I am initiated into a new world, a new way of seeing, being and understanding everything around me. That is why I have made annual pilgrimages to Thailand every year since 2014. Coming to the temple is like coming home to myself, it is where the missing puzzle pieces of who I am fall into place and the picture that is me makes sense. It may sound strange to travel ten thousand miles to a country where I do not speak the language to find myself, but that is how it has always been. When I sit in the presence of my spiritual teacher, I become whole.

I guess you could say my heart expands in response to her love, I become a more authentic, happier, joyful version of myself.

You may also enjoy reading Dying Every Day: Exploring Life and the Near-Death Experience with Reincarnate Buddhist Lama Mingyur Rinpoche, by Peter Occhiogrosso.