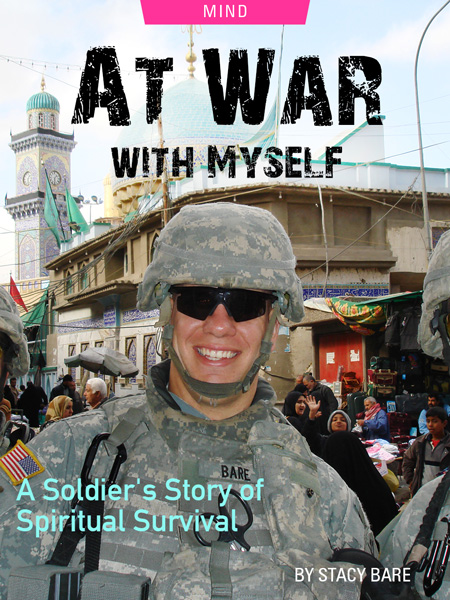

A soldier discovers his true mission and the power of nature as he heals deep psychic wounds inflicted by war — and the survivor’s guilt that followed

—

I never thought I would live this long.

This past Veterans Day, I realized that was both a conscious and an unconscious thought that had ruled the last couple years of my life. I’ve doubted my successes. I questioned my choices all in the context of the belief that I simply wasn’t supposed to be here. I felt like I was cheating and stealing from those for whose living was more justified.

When I first came home from Iraq 12 years ago, I questioned why I lived and others with more to live for — kids, communities, careers, and lovers — did not. Why did I — a single man without a partner, kids, career, or community to call home (or so I thought) — survive when others did not?

This feeling I now had, however, was not that. I was over the initial shock of survival a few years after my return home.

Now, I was questioning why was I still alive?

Cocaine had come and gone, as had alcoholism. I had a long run of personal and professional success. I had outlived most of the worst statistics of my generation of veterans, but now what? Why was I still here when I felt unwanted, unneeded, and unable to fit any more?

Two years ago, I felt like the top of the world was just over the next rise. After being recruited away from my job to be an executive for a company whose values felt closely aligned with my own, it seemed that I was taking a step up the career ladder. Research I had been a part of — about the power of the outdoors to support healing from trauma — was received with great fanfare… I had success with my second film project — Skiing in Iraq — that had me returning to places I had been during war or cleaning up after war. I was confident that the next film project I’d tackle would find funding easily and give me enough time to film it and still leave me enough time to be with my family.

I was nearing 40, but as I excitedly told my wife, I felt like I was just starting. A few months later, this train got derailed. My new job and I were not a good fit. I left to pursue other goals. I set up shop as a ‘consultant’ in my extra bedroom. I wrote half-hearted emails to potential clients. I jealously watched my friends and peers accept positions of increasing responsibility, get projects funded, achieve great things, and acquire impressive titles. I mythologized their grandeur as I stared out the basement window to the base of my backyard fence. I promised myself that my situation was just short term.

I surprised myself by landing a few clients. I was excited about my work helping organizations with similar values as my own, do their work better. A few other friends were hanging out shingles of their own and a few joint projects made the future feel bright once again. Together we could make a bigger impact in our freelancing / entrepreneurial exercises than we could on our own. Recruiters kept calling. I figured it couldn’t hurt to keep interviewing. After preparing for hours and putting on a shirt and tie, I made it through to a few final interviews, excited about the prospect of full-time work at someone else’s organization. I played the conversations over in my head about how I’d tell my fellow freelancers goodbye. Inevitably though, I’d wait a couple of days and get a phone call that started off positively, “We think you’re great…” before shifting to a “but…” and end with, “we can’t wait to see what you do next.” Meanwhile, my collaborative partners shared with me they were moving on as they collected full-time jobs.

I got depressed. I acted like a jerk to my wife and to my close friends. Nobody, I told myself, wanted what I had. What was wrong with me?

What was wrong with other people? How come everyone else could find a fit in government/corporate/non-profit America? To answer these questions, I needed to look back on my life.

The War

My Mom reminded me the other day that when I was five years old, I told her I wanted to be in the Army or Navy. My Grandpa, a first-generation American whose parents were Czech, served in the Pacific Theater with the US Navy in World War II. My great aunt, the sister of my Grandpa’s wife, also served in the Pacific Theater as part of the Women’s Army Corps. My uncle was a Green Beret in Vietnam as well as my pediatric dentist and orthodontist; he was skilled at torture. Each of these relatives were great role models, but Grandpa was the winner — so if he was in the Navy, I was going to be in the Navy. Unfortunately, at my tall height (just over 6’4” at the time — I’d max out at 6’7”), the Navy required a medical waiver. The Army, however, was delighted to have me without any extra paperwork, so a soldier I’d be!

At the age of 17, I enrolled in an ROTC program at the University of Mississippi. My Dad had to sign my paperwork since I wasn’t legally an adult. After four years of college, I had a guaranteed job in the Army and a philosophy degree to show for my intellectual bravery when, on a steamy day in May 2000, I headed to Ft. Huachuca, AZ before a permanent duty assignment in Darmstadt, Germany.

The next four years flew by in a blur. Prior to 9/11, the worst deployment one could get was Kosovo — Bosnia being the preferred choice — but fewer and fewer soldiers were getting deployed at all. We sang cadences in training and on long runs that begged for ‘somebody anybody start a war-eh!’

Then finally, somebody did.

I didn’t question why the United States wanted to invade Afghanistan. I assumed our engagement in Afghanistan would end quickly. I was most excited to finally be a soldier at war. This was what I had wanted since I was in kindergarten. This was what I had been training for the last five years.

But when the U.S. mobilized forces and invaded Afghanistan, I was left behind through no fault of my own. My unit was strategic intelligence. There aren’t any great books written about it because it didn’t participate in any of the cool battles or wars I read about growing up. Some of our unit got farmed out to other units. Most of us however, stayed at home in our highly protected, secure, containerized, intelligence facility (SCIF) in a rural area at the edge of the suburbs of Darmstadt. Our biggest threat seemed to be an angry dog that would sometimes break free from one of the local Germans out on a walk in the trails around the fenced-in facility.

Nonetheless, I tried hard to get myself deployed to Afghanistan.

I spent my lunch breaks calling around to other units begging other commanders to get me attached to the deploying unit. I needed orders from another unit so I could be released from a job that entailed what seemed like an obscene amount of time spent crafting PowerPoint presentations. No luck.

Later, when we made plans to invade Iraq, I was leading the one platoon that spent a good amount of time in the field within the larger Intelligence group. I figured I’d be a shoe-in for getting to go to war by invading Iraq through Turkey. The Turks, however, never gave us permission. As a result, half of my unit made it to Turkey, while the rest of us stayed home and eventually drove everyone back from the airport. I assumed Iraq would be a short war as well.

I was 0 for 2 for fighting the wars of my generation before getting a six-month deployment to Bosnia.

This was an incredible opportunity and a challenging assignment — a combat zone, according to the hazardous pay I received — but I felt like I was cheating those who had been asked to fight a ‘real war’ in Iraq or Afghanistan. In 2004, I tried to extend my tour in Sarajevo, but the Army said no. So I said no to the Army. I quit.

I felt guilty leaving. Especially since many of my friends and colleagues were coming home with things like PTSD, Adjustment Disorder, missing limbs, or numerous other physical and mental aches and pains. But the dream I had hoped for when I finally got my commission did not match up with the reality of service.

No doubt, I met a lot of great people during my time in the military, especially my fellow soldiers and NCOs. There were definitely some special cases in the junior ranks, but most of the shitbags were a few rungs up the ladder from me. I had a few leaders that seemed intent on crushing morale, confusing their subordinates, and peacocking around the office mandating endless changes to reams of PowerPoint slides that, while full of information, told the viewer nothing.

I knew it was time to leave the military, but I had no idea what I was going to do next. The Army was supposed to be my dream, and my dream was supposed to last 20 years. It did not.

In a last-minute bid to stay, or rather return to Sarajevo, I did an internet search for land mine clearance organizations and applied to the first three companies that popped up in my search results. Surprisingly, I got a job. Instead of a trip back to Bosnia, I was sent down to Angola. After nine months, I experienced some medical complications. That’s when I was moved to Abkhazia, a breakaway province in the Republic of Georgia nestled between the Caucus Mountains and the Black Sea.

Nine months into my stay, with a promotion glowing in the future, I got an email from the United States Army welcoming me back to service. My reaction was both sad and nervous. I had grown to love the life I was living. I was about to receive a promotion. I was dating an incredible woman. All of that was going to be taken away if I went off to fight in a war that, upon further reflection (or first reflection to be honest), I wasn’t sure I supported.

Stronger than those emotions, however, was a sense of relief. Relief that I would have a chance to go fight in my generation’s war. Relief that I would be able to make, or at least offer, the same sacrifice my friends and colleagues were making. My friends in the international community who had not served did not understand why I felt this way. I did not blame them. One friend with connections high up in his home country, made me an offer of political asylum. I knew I’d never take it. It was, however, one of the kindest gestures anyone has ever offered me. “Don’t let them take your life for an unworthy cause,” he pleaded.

But I was puffed up with pride as I prepared to return to life in the military. The dream I had at age five was going to come true… again.

After a few weeks of leave, I signed into Ft. Bragg along with hundreds of other men and women who had been recalled to service out of the Individual Ready Reserve. I was asked if I needed to delay my urinalysis to prove I was drug-free. During our first physical fitness test, we were all told not to push ourselves too hard. Apparently, the Army was desperate for bodies.

Just after Easter, we flew to Baghdad. My first five months in the country were primarily staff work — everything I feared I would have to do in the Army when I left the first time. I took in reports from the five Civil Affairs teams assigned to cover the entirety of Western Baghdad. I did my best to create a cohesive picture for my commanders of how the United States Army was winning the hearts and minds of the Iraqi people.

A few times I got to go off base — ‘outside of the wire’ — to actually visit the people I was there trying to help. One of the missions I had recommended to my boss, and that he signed off on, was to support a group of farmers who did not have access to sorely needed vaccines for their livestock. I had originally received permission to go on the mission with the veterinarian and team. I wanted to go to see if what I was thinking was helpful both to US goals as well as Iraqi’s. Unfortunately, I ended up staying behind because, no lie, I needed to update the color of yellow I had used on a PowerPoint presentation. As I walked to the gun rack where LTC Daniel Holland, VD was putting on his Kevlar helmet and grabbing his rifle, I said, “I can’t go Colonel. More PowerPoint for the boss.” “No worries,” he said excitedly, “There will be plenty more vaccinations!” I shook his hand, told him to be safe, and sat back down to more PowerPoint.

Two hours later his vehicle, which I was supposed to be in, drove over an improvised explosive device that was planted in the middle of a bridge.

The explosion killed all five people in the HMMWV. There were not enough recognizable pieces of bodies to be put into the caskets that would be draped with flags and sent home empty.

In the aftermath of this deadly explosion, the sergeant in charge of that team decided to not go outside the wire again. The team leader decided his best course of action for the remainder of his tour was to stay in his room and play video games. I heard later he returned to Iraq a few more times.

I blame neither man for their actions after the explosion. With a team leader slot now open, I was able to negotiate a transfer out of my job and into the vacant position. I was 28 years old. After 23 years of waiting, I was finally going to war.

I loved my job in Iraq. I loved my team. I loved the people we met every day on the streets of Baghdad.

Yes, we got shot at and blown up. But yes, we also got to work with people who, every day, despite the myriad threats on their lives, showed up to do good work for their community.

On one of my last patrols, my team got blown up. Had the individuals who attacked us timed the blast a little better, I may not be here today. Instead, our truck’s tires took the bulk of the damage along with the front of our HMMWV. We saw four Iraqis killed by our team returning fire from the ambush zone. Later that day, at a meeting with the neighborhood leadership council, the council leader told me he was glad I was okay. He encouraged me not to take the attack personally. I wish there was a photo of the look on my face after he said that.I was simultaneously dumbfounded and furious.

Years later, I understood what he meant. The young men who attacked us were not necessarily trying to kill us. They may have even loved what they knew of America. Someone gave them a good enough reason to risk their lives in the attack, just like someone had given me a good enough reason to risk my life in Iraq. It is those ‘someones’ I wish waged wars, the ones who do the convincing, not the convinced.

A couple of days after we got blown up, I took my last patrol in Baghdad. My last act of war was giving up on replacing the dried-out gauze covering burns that had consumed about 90% of a young girl, maybe four or five years old. She lived in an internally displaced persons camp in view of a hospital. The skin underneath her gauze was necrotizing. Our attempts to help her only caused more pain. One of my soldiers took out his patrol cap and passed it around to collect hundreds of dollars for her medical treatment. After giving the money to the girl’s mother, we got back into our HMMWVs and drove back to base.

Seven days later I was back at Fort Bragg. A few hours after landing I ate dinner at an Outback Steakhouse, got shit-faced drunk, and closed down a strip club. Four days later, I called the government travel agent to tell them I had to get home because my girlfriend was expecting. I got on a flight that afternoon, but not before I stopped at a dumpster as I left base to throw away my military gear I didn’t have to return.

I did not have a girlfriend.

I was glad to be out of the Army, but I still felt guilty for coming home. I felt like I had abandoned my friends, Iraqi and American.

I was afraid I would not live up to the expectations I placed on myself for getting to live when many of my friends did not. If things happen for a reason, this one was a bad one and made no sense. I never heard my Grandpa or Great Aunt, even my Uncle, talk about any of this.

The Shift

After a few weeks of traveling around the States and overseas visiting friends and far flung beach towns trying to surf I moved to Philadelphia. I settled into life as a hard-partying graduate student… I was the only veteran in my cohort of fifty students. I remember one classmate expressing surprise that I had been to war. “The only other person I know who fought in a war was my grandpa,” he said. Graduate school provided me with an easy identity. I knew what to do each day and every night and a lot of mornings. I was able to drink copious amounts of booze and inhale piles of cocaine to get through the day. My life was burning down, but I did a good job hiding the worst of the fire from everyone I knew.

I graduated with an Urban Design degree at the height of the last economic meltdown in 2009. I found a job with a start-up non-profit working to get veterans into ‘green’ careers. Alone in Boulder, CO with few friends and the woman who would become my wife, I routinely called a friend, Chuck, I had served with in Baghdad who lived in nearby Colorado Springs. Our conversations centered around my discontent in my post-military existence. As happy as I was to have left the service, I was now ready to go back in because that is where I knew who I was. It was either that or end it all: suicide.

As happy as I originally was to have left the service, I was now ready to go back in because that is where I knew who I was. It was either that or end it all: suicide.

After a few phone calls, he encouraged me to do something, anything, that would move me away from this mindset. “But what?” I whined. “Come climbing with me. Get yourself the gear and we’ll meet up on the 20th.” If I was going to die by suicide, waiting a couple of weeks was inconsequential, so on a weekday, I didn’t call in sick or ask for the day off. I just went climbing.

I was scared and nervous. My ego was in fits because I didn’t want to look like an idiot. Turns out though, I didn’t want to die, or even fall too far. So every opportunity I had to tumble down the rock, I clung hard to whatever hand hold or foot hold was available. Long before I even felt a fall coming, I yelled to Chuck to take up slack on the rope. Then we climbed on.

When I got to the top of the climb, I was exhausted, but amazed! What had I just done? I looked into the Rocky Mountains beyond the Front Range and down to the prairies in front of me. I was awed by the beauty I had been missing. As I tied into the rope to rappel down, I lost it. I began to shake and cry. All the pain and stress of the last two years of addiction, my year at war, perhaps even my years of feeling guilty for not going to war — all came coursing through me.

I know now I had a somatic experience. At the time though, after Chuck calmed me down and got me to the ground, I realized it was the first day in two years that I had not been fearful of my past or guilty about my future.

That climb saved my life. It gave me a reason to be. If it could be this good for me, I thought, how good could it be for other veterans, especially those who fared far worse than me?

This realization changed the course of my life.

Eight months later I’d quit my full-time job to found Veterans Expeditions. My co-founder, Nick Watson, had a guiding job with another company, Colorado Wilderness Rides and Guides, that supported our work as best they could. The rest of VetEx was paid for by a small grant from my brother’s high school ex-girlfriend’s little brother’s company along with a combination of my credit card and a few odd jobs I picked up along the way. I hauled furniture. I was an administrative assistant for a company that did insulation and energy audits. I hawked concert and sports tickets. I planned events (did you know there’s a difference between an eight- and ten-person round table? I do now). I did whatever I could to reach my goal: to get as many veterans into the outdoors as possible.

Ultimately this experience led to a position with the Sierra Club, first as the director of their military outdoors program, and later overseeing the entire Sierra Club Outdoors serving veterans, service members, and non-military youth, and adults.

I came to realize that the power of time outdoors was not only an intrinsically healing experience for the mind and soul, but also a catalyst for deeper, more meaningful personal exploration — not just for veterans, but for all.

That’s why in 2014 I launched the Great Outdoors Lab with Dr. Dacher Keltner to put scientific data behind this transformative idea. That same year, I began to think about how time outdoors could be used to augment my personal experiences in war-torn nations. This led to the media project, Adventure Not War, which has resulted in a climbing project in Angola, skiing in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Surely this was all building to something bigger, something better, something more sustained. Only it wasn’t, or at least wouldn’t. Not in the way I wanted anyway.

Changing the Narrative

The phone calls and emails for client work kept coming in. Small projects, sure, but enough to keep the mortgage paid. My next film project after Iraq, documenting the ski culture in Afghanistan, got funded by the family foundation of the fiancé of a friend I served with in Iraq. Small brand partners filled in the gaps after large brand partners, many of whom I’d been with for several years, walked away. My approach was too different; my films too intimate and dark, they didn’t “want to be associated with an American getting kidnapped and beheaded,” but they were “excited to see the project if I finished it.”

At the time, I couldn’t see the value of all the ‘yeses’ I was getting. The ‘nos’, from larger and more prestigious pocketbooks, were what reverberated in my head.

The irony of this was that the reason I went back to Iraq, and wanted to go to Afghanistan in the first place, was to reshape my own narrative and interactions with each country into something more positive than conflict, war, death, and explosions. Rather than going into these countries with a gun in hand, my goal was to find the spaces that remained beautiful and to seek out joy.

It was a small team that went to Afghanistan. Myself and two filmmakers. Western military contractors stared aghast as we moved through airport security with ski and snowboard bags and the Afghans who became our guides for our nearly three weeks there. I had no Kevlar vest to put on, no assault rifle to manage, but we did have video cameras, outdoor gear, a healthy swivel on our heads, and plenty of smiles.

Our mission was to capture the beauty of these nations that too often are only remembered for the horrors that defined them in existing media narratives.

In Angola, Iraq, and Afghanistan, I was amazed at how generously we were welcomed as adventurous travelers with nothing more to give than our time to their landscape and culture.

Beauty exists everywhere — even if our global leadership at times seems intent on stamping it out. By shifting my own narrative about these places, I was also able to help shift other’s narratives about these locations as well. If nothing else, these expeditions and the films that we created encouraged viewers to stop and consider the positive in both the people and landscapes of war.

The Struggle

But back in my basement, I was stuck in a negative feedback loop of my own design. Perhaps the belief, or even the belief I thought others had that I would die, should have died, or even the fear that my life wasn’t worth saving after war, persisted deep in my psyche. I wrote off as mere coincidence or inconsequential any good news or positive reinforcement I received. I discounted the belief others had in my work and person. They weren’t the people I wanted to believe in me. They didn’t have the status, the funding, the cache in my mind, to bring me what I thought I wanted. In short, I was a selfish, self-centered, entitled asshole.

Yet, despite my best efforts to prove otherwise, many people continued to offer me a hand up, an open door, an introduction, enough funding to make the next project happen. But I couldn’t let go of that persistent thought: Shouldn’t I be dead anyway? After war, drugs, alcohol, and a pattern of poor decision-making, what right did I have to still be here?

This past Veterans Day, this swirl of doubt and confusion came together in one sweeping revelation. I was headed out to get a free oil change, thinking about the Afghan Ski Trip. I was thinking how much a friend who had died during our year in Iraq would have loved that trip, when the tears came. I pulled over onto a residential street in a suburb just south of Salt Lake City and cried ugly tears. I sent streams of viscous, thick snot all over my face and down into my beard in heaving sobs of tears.

That is when I realized that I had outlived every conscious and unconscious thought I had about surviving after war.

I had completed a significant part of my journey and done so with my health relatively intact. I had a wife I loved who loved me a back, a kid I adored who adored me back, a cat that slept on my chest just like a cat in Baghdad, a dog who wagged herself sick with excitement when I came into the house. For nine years I hadn’t had a single dangerous relapse with drugs or alcohol.

But for the last 12 years after returning from four years of war, I was so convinced that if my life wasn’t all perfect, it wasn’t all worth it. I had been fighting so hard for survival, so hard to prove I was worthy of the life others did not receive, that I didn’t know to even define success before those tears came.

Maybe all those ‘nos’ came because of my selfish entitlement. Maybe they came because I wasn’t the best candidate or my idea was really bad. Or maybe they came because I was simply too afraid. Or maybe, it had nothing to do with me at all. But on the other side, what about all those ‘yeses’? All those people who saw the spark, got a glimpse of the vision, felt the potential sliding into a glorious reality? Were they all lying or misguided, or were they able to see clearly what I could not?

The Awakening

As the sobs began to subside, I decided it was time to lean into those who believed; to try to match their belief in me with my belief in myself. I figured those who had shown time and time again that they wanted what was best for me were making sense. It was time to go back and ask for the help that had been offered but never accepted.

It was time to accept that when the help came, I had to do my part as well. I also had to recognize that I was committed to keep living.

No matter who you are or where you are, it can all be taken away in a moment’s notice, but that is not a reason not to work to create something big, bold, and beautiful. Doing that is hard and almost always necessitates copious amounts of failure, no’s, setbacks, and ‘not quites’, before yes is found. And that, I think, is the crux of it all.

Yes, I survived. It was a vainglorious effort and the odds were stacked against me — as they are stacked against each one of us to varying degrees war or not. But the privilege was also stacked in my favor, even if I tried to ignore it, was angry I had it, jealous that others more deserving of me didn’t get it, or because it didn’t show up in the package I wanted.

So how did I shift from a survivalist mindset to one of thriving, or at least living?

The first step is a reminder that past success, just like past failure, doesn’t determine the future.

There’s a good chance I’ll be back hawking tickets or moving furniture or something else, but this time with a sense of joy to be living. As for what needs to come next, it’s the same thing it has always been from that first climb: To promote the transformative power of adventure by building a community around that goal, without having to know what the journey, or even the destination will be moving forward.

Second, I get to define what success looks like in my life — no one else’s — though it’s nice to collaborate with family and loved ones.

I’ve also had a lot of success. I need to embrace the lessons learned from the real failures, without tipping the balance to live in those failures and shortcomings (or successes), as if they are the only thing that defines me.

Third, I need to set priorities that allow me to move through my life with purpose.

Plenty of other amazing things out there could await me, but they all start by focusing on the act of not just everyday living, but everyday living through my purpose.

Fourth, I need to celebrate the lives of those I’ve lost, not just in Baghdad but in the years before and after the war.

I don’t need to feel guilty if a day goes by when I don’t remember everyone. But when I do, I need to remember their smiles and their gratitude for the time they got. It could all end tomorrow regardless of my success or failure since life is mostly, but not always, out of my control.

I’m so happy my life fell apart — even though it did take the better part of a day to get all that snot washed out of my beard.

You may also enjoy watching Interview: Brendon Burchard | Live, Love, Matter with Kristen Noel