A discussion with a modern day lama who breaks with tradition in his journey of self-discovery that includes an anonymous wandering retreat and a near-death experience

_

“How many of you did not understand anything I just said? Please raise your hands.”

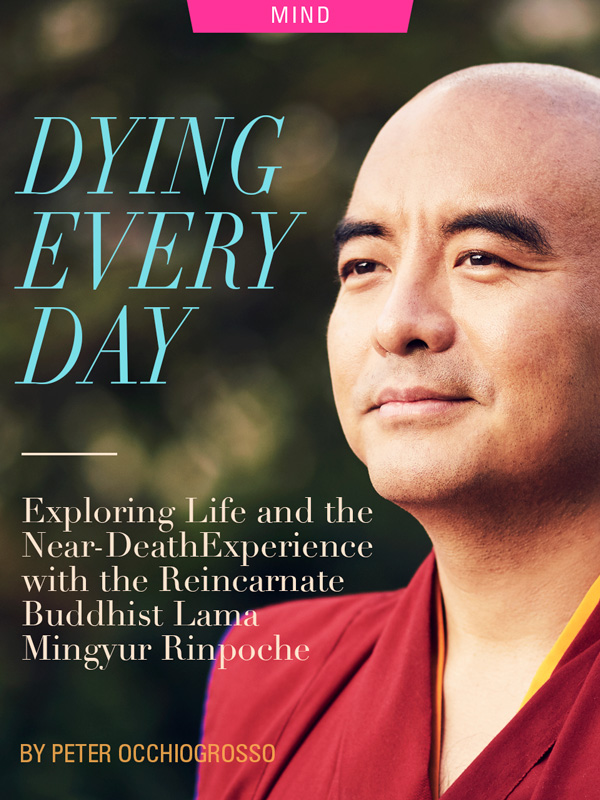

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche is addressing a crowd of 200 people in an auditorium on the campus of St. Thomas University, a Catholic college located in a residential area of St. Paul, Minnesota. On the second day of the Path of Liberation retreat that I’m attending, he has just spent more than an hour attempting to explain a profoundly subtle concept of meditation often called “nature of mind.” One reason I came all this way to spend a week with Mingyur and his team of master instructors was to learn how to recognize the nature of mind, a key to practicing Mahamudra, the highest level of meditative awareness in Tibetan Buddhism.

Still in his mid-forties, Mingyur Rinpoche is already one of the most popular, and most highly respected, teachers in the world of Tibetan Buddhism—a world that presents a Buddhism that, some Buddhists might argue, diverges from the teachings that the Buddha himself propounded some 2,500 years ago in northern India and what is now Nepal. Although the historical figure of Shakyamuni Buddha taught a way of life that relies entirely on one’s own human efforts, the Vajrayana tradition in which Mingyur and his fellow Tibetans work is replete with deities and celestial beings, male and female, although nothing quite like the Supreme Being of the Western Abrahamic faiths.

The Buddha did accept the gods and demigods of the Indic culture of his day, but believed them to be inferior to the human realm because only humans can become enlightened. Most Western followers now view Tibetan deities like Chenrezig, the bodhisattva of compassion, as metaphors for states of consciousness rather than actual beings, but the line can get blurry at times.

One key element of Tibetan Buddhism, however, is uniquely in touch with Western culture, both the aging baby boom generation of Americans now in their sixties and seventies and the Millennials, who are watching their futures go up in smoke:

None of the world’s major religious traditions has focused more of its teachings on the dying process, an event that looms larger than ever for many of us.

And yet, far from reflecting a morose obsession with the end of physical life, the Tibetans offer some of the most practical, empirical aids not only for seeing death as a positive experience, but also for learning how to undergo it with the least suffering and the greatest opportunity for transformation as consciousness continues in its next stage. An advanced practice known as phowa, for instance, designed to teach practitioners how to direct the transference of consciousness at the time of death, either for oneself or another, has virtually no counterpart in other religious traditions, nor in modern science, for that matter.

Even if you don’t believe in an afterlife or rebirth, simply knowing how to die consciously and without mind-clouding drugs can clearly be beneficial.

Even more to the point, the Tibetan view of the dying process also aligns closely with our current understanding of the near-death experience, or NDE, which has become a subject of intense interest in recent years. The Tibetan Book of the Dead—also known by its original Tibetan title of the Bardo Thodol, or “Liberation through Listening in the Between”—is the most popular of all the books in the Tibetan canon among Westerners.

Perhaps no sacred text more thoroughly explicates the process one’s consciousness goes through during and immediately after dying. Dr. Raymond Moody, whose 1975 classic Life After Life introduced the term near-death experience, and became a bestseller, was aware of the Bardo Thodol, which had been first translated into English in 1927. Moody found it astonishingly cognate with the one hundred or so NDEs he had been documenting. “The book contains a lengthy description of the various stages through which the soul goes after physical death,” he wrote in Life After Life. “The correspondence between the early stages of death which it relates and those which have been recounted to me by those who have come near to death is nothing short of fantastic.”

The goal of that text is to help readers recognize and navigate the several bardos, or “in-between” states during which the possibility of achieving enlightenment, or liberation from the wheel of suffering known as samsara, is greatly heightened. Composed in the 8th century by the Buddhist adept Padmasambhava, whose consort, the Tibetan princess Yeshe Tsogyal, wrote down this and other texts and hid them in various locations, the Bardo Thodol was discovered and revealed some six centuries later and has been recently translated into English any number of times.

However, for all its popularity—it was a favorite of Timothy Leary and served as the inspiration for the Beatles’ song “Tomorrow Never Knows”—the Bardo Thodol is also famously dense and difficult to follow. One reason I was eager to attend Mingyur’s retreat in St. Paul, besides the rare opportunity to learn more about Mahamudra from a genuine master, was that I had just finished reading his latest book, In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying (written with Helen Tworkov; Spiegel & Grau, 2019). To my knowledge, it’s the first book by a modern Tibetan lama about his own near-death experience, and it’s nothing short of breathtaking.

After deciding to leave his all-too-comfortable life as the abbot of a large monastery in India and go on an anonymous wandering retreat, Mingyur finds himself immersed in a world that is as unsettling to the young lama (he was just 36 at the time) as it will be discomfiting to most Western readers—sleeping in vermin-infested train stations, begging for food, and nearly fatally sickened by the tainted scraps he is given.

But along the way, even as he struggles to overcome his own aversion and physical pain, Mingyur misses no chance to teach readers what he has learned from his intensive years-long study of the Bardo Thodol. Sharing his insights, he persistently invokes the voices of his teachers, most notably his father, a renowned meditation master himself, who practiced not so much tough love as continuous instruction illuminated by a series of appealing stories.

With his father’s guidance, Mingyur had studied the text in the original Tibetan and trained in the necessary skills to maintain his awareness during the process of dying. And so, when it slowly dawns on him that he might well be expiring of food poisoning and dysentery, rather than taking himself to a nearby clinic—where he would most likely have been treated, even without funds—he chooses to tough it out by drawing on his training and doing his best to “maintain awareness.” In the process, he enters what is clearly a near-death experience, although it may not be quite what you expect.

In the 44 years since Raymond Moody’s Life After Life was published, near-death experiences have been reported by tens of millions of people from all walks of life and many nations. Moreover, these experiences have occurred under conditions of rigorous observation, often by cardiologists and other medical professionals, and in numbers too great to ascribe to mere chance, delusion, or fabrication. Enough books about the subject have now been published to rate their own shelf in any sizable book store, while many have become number one bestsellers—and I get why that is. They can make for fascinating reading, more so if you’re open to the concept that when people “almost die,” they undergo extraordinary experiences, which you’ve probably read about by now: encounters with deceased loved ones and/or beings of light; feelings of indescribable bliss and love; the ability to observe from above medical personnel or family trying to revive them; and often a life review reminiscent of scenes from the Hollywood film It’s a Wonderful Life. I’ve read enough of these books, dozens actually, to know how they usually go, so I should announce upfront (spoiler alert!) that Mingyur’s description features few of those standard elements.

What it offers instead is a step-by-step appreciation of how everyday life consists of various stages of dying in small and significant ways, how best to deal with those moments, and how they are preparing us for the physical death of the body—and the continuity of consciousness that accounts of NDEs imply.

The Tibetan word bardo refers to more than just the stage between death and either enlightenment or rebirth, as described in the Bardo Thodol. As Mingyur points out, learning how to navigate the transitions, or in-between moments, in everyday life can be as valuable as understanding what we may face as we approach physical death. “Anything that interferes with mindless repetition can function as a wake-up call, and an antidote to automatic, mindless behavior and habitual fixations,” he writes in his new book. After enduring his first hellish train journey upon leaving his monastery under dark of night, and his own shock at realizing how much suffering ordinary people endure outside the closed world of a highly respected abbot, Mingyur spends some of the small amount of money he took with him to rent a room in a local “pilgrimage hostel” and purchase inexpensive treats like dal with rice. But he quickly runs out of funds and is forced to go to a nearby restaurant where he had been paying for his food and beg for a handout. He is told to return in the evening, when they will distribute the day’s leftovers scraped from customers’ plates.

The food they give him turns out to be toxic, and within a short time he begins to feel the intense pain associated with food poisoning and its attendant dysentery. No longer able to pay for lodging in the hostel, Mingyur takes up residence outdoors in a park surrounding the Cremation Stupa in Kushinagar, where the Buddha’s body was immolated—as good a place as any to meditate on the likelihood of death. Steadfastly resisting medical help, he instead focuses on maintaining meditative awareness and tracking his progress through the bardo of dying as he had learned. And, as his physical self steadily deteriorates, he takes us with him on his hallucinatory yet remarkably cogent interior journey.

* * *

Mingyur Rinpoche may be the teacher most ideally suited to interpret the wisdom of the bardos and other elements of Tibetan teachings known collectively as the Dharma to a Western and worldwide audience for a number of reasons. His first book, The Joy of Living (2007), was a New York Times bestseller that successfully interpreted the basics of Buddhist practice for a non-Buddhist readership, and he has written several more books that have also sold well—to Buddhists and non-Buddhists—and have been translated into a dozen languages. He now has large established communities in the U.S., Mexico, Brazil, France, Germany, Denmark, and Russia, and his “Guided Meditation on the Body, Space, and Awareness” video has over 2 million views on YouTube. (It may be the best 15-minute “how to meditate” video I’ve ever watched.) And Netflix has just featured him on the “Mindfulness” episode of their new series The Mind, Explained.

Among Mingyur’s better-known American students are the renowned meditation research neuroscientist Richard Davidson (also featured in that Netflix series) and the celebrated performance and virtual reality artist Laurie Anderson. (Lou Reed, her late husband, was also a follower.) Anderson has said that she often quotes Mingyur in her work and that her favorite teaching of his is, “Try to practice how to be sad without actually being sad.” In an email, she added, “This is a colossal, mind-shaking distinction that has changed my life.” She has also just released a new recording, Songs from the Bardo, in which she reads excerpts from the Bardo Thodol with musical accompaniment.

Indeed, I spied Laurie while checking in for the retreat, her spiky hair and cherubic face little changed in the years since she was a leading performance artist in the 1970s (although we all left her in peace). The rest of the audience ranged in age from millennials to folks in their sixties and seventies who, like me, mainly sat on comfortable chairs because they could no longer manage the flexibility required to rest on a cushion in the classic full-lotus, or even less-demanding alternatives. They also varied in experience from having meditated for decades to only recently having started on the Buddhist path. We were all there to learn how to recognize the nature of mind, which may sound simple enough to anyone unfamiliar with the lineages of Tibetan Buddhism of which Mingyur is a master, yet which is anything but.

The nature of mind refers to a state of awareness entirely unobscured by mental concepts or beliefs—something Zen Buddhists call our “true nature,” and that Vedanta practitioners refer to as “nondual awareness.”

The Buddhist scholar-practitioner John Myrdhin Reynolds puts it this way in his commentary on another ancient text from the same treasure trove that gave us the Bardo Thodol: “The nature of the mind is like a mirror which has the natural and inherent capacity to reflect whatever is set before it, whether beautiful or ugly; but these reflections in no way affect or modify the nature of the mirror. . . . This nature of the mind transcends the specific contents of mind, that is, the incessant stream of thoughts continuously arising in the mind which reflects our psychological, cultural, and social conditioning.” That may be as succinct definition as I have found. The main problem is that, because this “capacity to reflect” is nonconceptual, it cannot be fully described in words, so Mingyur has been trying to tease an experience of the nature of mind out of us with questions that, to be honest, sound starkly futile. “Look at your thought,” he says with an open expression on his face, “and ask yourself if it has a shape. Or a color.”

The Zen tradition, which in many ways is quite different from Tibetan Buddhism, hints at the difficulty of recognizing mind in a koan that appears in Case 23 of the koan collection Mumonkan, or “Gateless Gate,” when a Zen master demands of his student, “Show me your Original Face, the face you had before your parents were born.” What they are pointing at is akin to what we in the West might call the soul, or that core essence of each of us that exists outside of time and space, nationality and gender, and will survive death. The Tibetan iteration is perhaps more straightforward, but hardly less befuddling. “Look back at your mind,” Mingyur says, switching to a favorite metaphor. “If you can see the river, you’re out of the river. If you see the river, it doesn’t matter what kind of river it is: dirty river, clear river, turbulent or calm river. But if you fall in the river, you should have a calm river, nice temperature, clear river. You don’t want to fall into a dirty river.”

Applying this image to meditation practice, he clarifies: “If you can see the discomfort you’re feeling, you don’t need to stop feeling it. You can have a healthy sense of me, an unhealthy sense of me, or a luminous me. The unhealthy sense of me is very sensitive, black and white, very narrow. You cannot fight with it. If you believe this unhealthy sense of me is Yes sir!” (snapping to mock attention) “then it becomes your crazy boss. So, what we have to do is make friends. Say, Hi! and face it. On the cognitive level you ask, ‘Who am I?’ And on the meditative level, just be aware of it.”

Mingyur goes on like this for a while, suggesting that we ask ourselves, regarding our everyday actions and choices, “Who’s the boss?” (He is especially adept at turning colloquial American lingo to good use.) By this he means to ask ourselves which of the three elements that are considered key in Tibetan philosophy—body, speech, and mind—is calling the shots. Back in the mid-20th century, the legendary Indian sage Ramana Maharshi developed a following by asking anyone who made the pilgrimage to the holy Mount Arunachala in South India, where he regularly held forth, a simple question: “Who are you?” However his visitor responded—with their name, nationality, occupation, philosophy of life—Ramana would simply repeat the same question. Again, and again, and again, until, at last, the seeker fell into silence. He recommended that all those who sought his counsel ask themselves the same question continuously.

Looking for the nature of mind by following Mingyur’s clues is not unlike Ramana’s prescription, although it gets more complicated as you progress.

Am I the person having this thought—the person having this momentary feeling of anger, or lust, or serenity? Or am I the person aware of myself having this thought or this feeling?

One purpose of the retreat is to receive what are called “pointing out instructions”—by which a realized teacher helps you to directly experience the nature of mind. These instructions are traditionally given in private, although one of Mingyur’s team of senior instructors (Western masters who also teach throughout the retreat) had assured me that he has developed a way to do this simultaneously with large groups.

After continuing in this vein for a good twenty minutes or so, Mingyur, perhaps catching the vibe of silent obfuscation sweeping the audience, asks the question that opened this article: “How many of you did not understand anything I just said?”

Virtually every hand in the room, including mine, shoots up—the first time he’s gotten such an unambiguous response. Mingyur’s initial reaction is a look of genuine disbelief. He probably expected to have lost maybe half the group, but he seems momentarily stunned by this show of near-universal incomprehension. His shocked look freezes—and then he bursts into uproarious laughter, an infectious howl that has us echoing him with our own confused amusement. But that only sets him off further. At first he throws his hands up in mock incredulity. But then something else, something larger, seems to overtake him, and his laughter becomes almost hysterical. He continues the upward sweep of his hands back over his head and then behind him. Finally, he throws his whole body back until he is laid out completely supine, eyes facing the ceiling. This is almost painful to watch because he was already sitting in a full lotus on the silken “throne” that serves as his dais. His legs still wrapped in the lotus posture, he must be eerily flexible to be able to lay out in a full backwards 180.

That’s when I realize that maybe he’s laughing at himself as much as at us, laughing at the cosmic joke of thinking he can expect several hundred people to instantly grasp the kind of subtle mind-training that most monks spend years in a cave learning.

And flexible is surely the right word. His own life has required the kind of mental and emotional elasticity that would make a contortionist envious. Mingyur was born 44 years ago in the foothills of the Himalayas, not far from where the Buddha himself grew up.

Like many Tibetans who came of age after the Chinese Communist invasion of Tibet in 1950, he was born outside the Motherland, in Nepal, and now lives perforce in India. He often speaks with real pride and gratefulness about being raised in the shadow of Mount Manaslu, the eighth-highest mountain in the world. His late father, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, who was born in Tibet and fled following the invasion, was a highly celebrated teacher of both Mahamudra and Dzogchen—two closely related forms of the highest level of meditation practice in the Tibetan traditions. Mingyur’s mother, Sonam Chodron, is descended from the two Tibetan kings who played key roles in importing Buddhism from India. He also has three older brothers who, like himself and his father, are recognized tulkus (indicated by the title of Rinpoche, pronounced RIN-po-SHAY), or reincarnations of lamas reaching back centuries. In Mingyur’s case, that would be to the first Yongey Mingyur, who died in 1708.

One of the first things that attracted me to the personality and teachings of Mingyur Rinpoche was his frankness about how much he suffered from anxiety as a child, something I’ve been trying to overcome since my own childhood experience at a Catholic parochial school.

As early as seven or eight, he endured anxiety that later grew into full-blown panic attacks triggered by events as quotidian as a thunderstorm, or the clangorous music of Tibetan horns and cymbals during monastic ritual prayer sessions. (Admittedly, the Tibetan music I’ve experienced here can be as ear- and mind-rattling as a Sun Ra concert, and nearly as exciting.) I had rarely heard lamas confessing their difficulties adapting to daily life, but Mingyur talked about how challenging he found meditation, even as taught by his father. During his first meditation instructions, he says, “I felt like I was driving a car with my feet on the gas and brake at the same time. Lots of energy, but no results.”

He finally got the knack, but his anxiety continued to manifest, often in unusual ways. In one of his books he describes his uncontrollable panic when, as a young teenager, his mother took him for the first time on a bus trip to Kathmandu. Having never before seen a bus or any comparable vehicle, he thought it was a huge, predatory beast—a perception that some adult urbanites can probably relate to. Nevertheless, he took the first of several traditional three-year retreats at age 13. By 20, he had become the functioning abbot of Sherab Ling, a major monastery that is part of the Tibetan diaspora in India, and later received full monastic ordination. In 2007, he oversaw the construction of Tergar Monastery in Bodh Gaya—the holy site in India where the Buddha is said to have obtained his Enlightenment.

Four years later, in the summer of 2011, Mingyur felt the call to leave a life that he says had become ultimately too cozy—and predictable—as abbot of a large monastery, waited on by attendants and sought out by thousands of students, monks, and Western seekers. He wanted to make a “wandering retreat,” in the tradition of not only the Buddha but also the itinerant ascetics and sadhus from whom the Buddha himself had learned—to cut his ties to safety as well as engrained habits. Mingyur later told the Buddhist magazine Lion’s Roar, “I had been meditating for many years, and of course I’m a meditation teacher, but I still had subtle pride, subtle ego.” His father told him that he had once tried to make a similar wandering retreat, but that his insistent students called him back, so he advised, “Don’t let anyone know.” Mingyur followed that counsel and escaped by calling a taxi to take him to the nearest train station (although he did leave a letter for his students, to be opened once his disappearance was noticed).

So began his plunge into an exceptionally turbulent, muddy river of unmediated life, in which he was to float for the next four and a half years. But he almost didn’t make it past his first month on the road when he ate that tainted food. His adventure is jam-packed. The first 48 hours of his journey—from one train station in Bodh Gaya to another in Varanasi—occupy almost half the book. Of course, much more is happening than travelogue, as harrowing as that is. Just riding on an Indian train in third class, so crowded that he is forced to sit on the floor with dozens of other travelers, sounds disconcerting even to those of us who have endured the New York subway system through its worst years. He uses the experience to explain the levels of meaning of the bardos.

“From the moment I left Tergar,” he writes, referring to his seat monastery in Bodh Gaya, “I was in-between in a literal way. Even on entering the train and getting a seat, I was in-between—as I was still, now, circling the station. Yet the true meaning of in-between has nothing to do with physical references but is about the anxiety of dislocation, of having left behind a mental zone of comfort, and not yet having arrived anywhere that restores that ease.”

And so, although we know this is all leading up to his near-death experience, Mingyur never takes the direct or predictable path, and even his apparent digressions are credible and gripping. That is largely thanks to his coauthor, Helen Tworkov, an accomplished writer and longtime practitioner. She keeps the narrative grounded by clarifying Mingyur’s explanations of both the complexities of the bardos and the dissolution of his senses as he nears death and then pulls back from the brink.

This approach has the distinct advantage of not requiring the reader to believe in anything “supernatural”—the great stumbling block thrown up by materialist scientists and atheists. I would even hazard to say that members of those overlapping demographics could read this book without having to abandon all their preconceptions. (Not entirely, of course. Sam Harris, one of the so-called Four Horsemen of the New Atheism, studied Mahamudra for several years with Mingyur’s father, and has created a meditation app based on what he learned. Nonetheless, he still rejects the veridical nature of the near-death experience.)

Interviewing Mingyur by phone before the retreat, I asked if he were familiar with the expansive literature of near-death experiences. He said that although he had heard about the books he hadn’t read any, so I described some of the most common aspects of NDEs and asked if they applied to his experience. “For me there was no other being helping, or any particular light leading me,” he replied.

“For me, it was that I tried to stay in awareness. Awareness is what we call ‘fundamental nature.’ Awareness is like sky, and then emotions, thoughts, perception, memory, whatever we are experiencing in our life—living or dying, it doesn’t matter. We perceive it like clouds.”

An oft-repeated Buddhist metaphor likens our inherent “buddha nature” or “primordial awareness” to the sun that constantly illumines the sky but that is temporarily obscured by clouds that pass in front of it. The clouds represent our ignorance and afflictive emotions such as anger, hatred, and jealousy. “When I was having this almost-dying experience—what I describe in my book as dissolving the elements in my body—I experienced these dissolutions,” he went on. “But my mind tried to stay in awareness: what we believe is present, pure, always there. Normally we do not recognize it. My father used to say that the bird flying in the sky doesn’t recognize sky, and the fish swimming in the water doesn’t recognize the water. We are living with this wonderful pure, present awareness, but we are not recognizing it.”

In his book Mingyur deftly describes this dissolution of elements that is believed to occur at death, his feeling that his body has become paralyzed and his senses have begun to liquefy, including his thoughts and emotions. And yet, he adds now, “At the same time, my mind was so vast, so present, so peaceful. I never felt like that in my life. When I felt all my senses’ dissolution, then what I felt was pure awareness. I stayed there for many hours within that state. And then somehow I came back to life. I began to feel my body, slowly I felt the senses. I could hear first, then I could see.”

After collapsing in the charnel ground, Mingyur is rescued by an Asian businessman with whom he had had been conversing off and on for several days before his illness set in. The man brings him to a nearby clinic (paying for his treatment), where Mingyur slowly recovers his health, although the process of nearly dying and then recovering occurs over many pages. As each of his senses gradually returns, he realizes that he is lying in a hospital of some sort, with no recollection of how he got here.

“And when I came back, the world had changed,” Mingyur told me in his sweet, small voice, which occasionally flies into the upper register when he becomes awestruck. “Before, when I was on the street, I felt like, Why had I come here? But when I came back, the street became like my home. This was a really big change, a big experience for me. But I didn’t feel a particular light, or that loved ones or someone had come to meet me.”

In his book, Mingyur admits to being “disappointed” to be back in his body after experiencing luminosity, and when I asked why, his reply was matter-of-fact.

“We believe that if you really die in that state, you’re free, you’re liberated,” he said. “You will achieve enlightenment. So sometimes I joke that it’s too bad that I came back to life again.”

And yet, he makes it clear that his return to the living was no accident. “In the end I felt a kind of strong love and compassion,” he said. “This is not the end, and for me to die—I sensed that I want to help others. Beyond concept, you can experience that compassion. And that feeling became stronger, and I think that was the main cause of bringing me to life again. When I came back to life, I had a strong feeling of gratitude, of appreciation for my life, about who I am. When I looked at the big trees in front of me [in the stupa park], they became really alive. It was like the trees were made of love. The sunlight and breeze flowing through my body felt pleasant, but more than pleasant. Before, it was just concepts, but now it was feeling, and the feeling was joy without grasping—contentment.”

I asked if his experience changed the way he teaches Dharma. “Before, I learned a lot of theory, a lot of cognitive aspects,” he replied. “But after that, it became more alive, more experiential. So when I teach, I now explore my own experience of what I call ‘head, heart, and habit.’ Head is the intellectual. Heart is the experiential—feelings. And the habit is bringing it into everyday life. So I try to bring my meditation into everyday life, and that really helps.”

And what about his life itself, I asked. How did his approach to living change? “That is where the title of my book comes from,” he said, his voice lighting up.

“When you love the world, the world loves you back. After that, I knew how to survive even though I didn’t have money or support.”

Having read that Mingyur was estimated to have spent more than 60,000 hours in meditation, I asked how his NDE was different from the profound experiences he must have undergone during prolonged meditation.

“I felt unlimited discovery within myself,” he said. “When we think about meditation, we think of it as peaceful, calm, and you will be more happy—but that’s all. It’s almost impossible to imagine beforehand, but as you practice, Wow! It’s Aha! My father told me when I was young that calm, pristine awareness is always there. I tried to practice that on a conceptual level but when I almost died, I didn’t have senses, I didn’t have thoughts as I normally understand them. Awareness is so vast, so present. No time. No front and back, no light and dark. I had this appreciation that death is not the end. Death is an illusion. There’s really no gap between this life and the next life.”

But, I asked, what about the Buddha’s teaching of “no soul” or “no self”—his famous proposition that we have no solid, continuously identifiable self that continues throughout this life, or from lifetime to lifetime?

“For me it’s just like thought,” Mingyur said. “One thought dies, another thought comes. I want to have water, and then I forget about it. Or I want to rest, or I want to have pizza.” Here he laughed. From his many videos it is clear that pizza, which he pronounces pee-suh, is a favorite food. “This concept comes from timeless awareness. Awareness cannot die. Yet, this awareness doesn’t have any kind of ‘thing’ that you can grab onto. It is almost invisible, beyond concept, and yet—it is so alive, so present. Because of this awareness, then, the thought comes and goes. And for me, death is like thought. Reincarnation, what we see, is only the literal level. But at the absolute level, no one is going to die. And no one is being born, also!”

I’ve read Robert Thurman’s excellent modern translation of the Bardo Thodol, but since I have yet to study its practices with a teacher, I asked for more guidance. I was also curious whether Mingyur thought the dying experience itself differed for people from different cultural backgrounds. “The Bardo Thodol says the most important practice is to just be with awareness,” he said. “But there’s a lot of perceptions, many different manifestations of lights or deities, or maras [emotional afflictions that can interfere with liberation].

There’s no limitation of what kind of experience you go through dying and after death. It depends on your culture, your faith, environment, your past experience; everybody is a little bit different.

It’s what we call ‘the perception of suchness’ or the perception of nature. That means there’s no limitation, although there’s so many different experiences of pure awareness—wisdom, love, compassion. Many people may experience different aspects of this awareness.

“There are many different states in the bardos. The first is experiencing the state of awareness without perception. And the second is you begin to have perceptions. Light is very important. And the sound of nature, the sound of dharmata,”he said, using a term forthe ultimate essence of reality. “Then your mind becomes more uncertain but you also feel love and peace, and everything is not so solid. Then slowly, conceptual things form again—you go through things in reverse—what we call ‘forward and backward.’ When you die, everything dissolves—consciousness, perceptions, memory—into pure awareness. Everybody experiences pure awareness, but the issue is whether you recognize it. When we recognize it, that is what we call liberation. If you don’t recognize it, you’ll be in that state for a while and then become unconscious. Then you wake up and begin the next journey. Awareness is always perfect, but recognition might not be.”

Here he burst briefly into his infectious, almost childlike laugh. Vajrayana teaches that we all have an opportunity for enlightenment, or liberation, following the moment of death, but we have to be alert and remain aware in that moment, or it will pass us by; then we will reenter the cycle of samsara and be reborn willy-nilly. Mingyur emphasizes that his own training in this area helped him have a positive experience. Since few most of us will probably not study the Bardo Thodol at length, however, he wants us to know there are other ways to prepare for the inevitable. Toward the end of his book, he writes,

“When we accept that we are dying every day, and that living cannot be separated from dying, then the bardos offer a map of the mind during this lifetime; and each stage offers invaluable guidance for how to live every day.”

This is clearly the main point of the book, his reason for writing it. During a livestreamed interview conducted by the psychologist Richard Davidson, who has made a life work of studying the beneficial effects of meditation, Mingyur told him, “I wanted to call my book Dying Every Day—but my publisher didn’t like that!” (I laughed out loud when I heard this all-too-true response from a commercial publisher.) Making the most of his practical approach to life, Mingyur writes that simple things like sneezing and yawning are the best opportunities to “interrupt the normal mind.” Apart from those involuntary actions, though, when would he recommend that people practice dying every day?

“Especially when you are facing problems,” he replied. “Say, you break up with someone, you lose your job, or when you’re 18 years old and you leave home—these in-between moments are the precious moments when we can really connect to who we are. If you know how to learn from that, be with that, embrace the situation, that’s when you can find who you are. If you cannot die, you cannot be reborn in this life.”

Those are major life events that can be trying, but they don’t happen every day. What about examples of dying a little bit each day?

“Let’s say you have some plans, and something can’t happen, you get a little bit of a shock,” Mingyur replied. “You have to let it go. If you’re waiting for the toilet and someone comes and cuts the line—again, it’s a big shock. At that moment, when an unexpected situation comes, our mind becomes Aha! It’s a little bit of a gap, a little bit of a nonconceptual state of mind. In that moment, we are really close to our true nature, who we are. So, if you are aware of that moment, then you will discover a lot of great things within yourself. Normally we are holding too much to the dry, conceptual level of who we are, what the world is, what the situation is. We have a lot of expectations, a lot of preconceptions. During this gap these preconceptions are gone. The important thing is to be aware and be with that, and that’s when great ideas come. Great knowledge, great insight comes out of those moments. When you look at history, the great people’s life stories, their great insights come during this gap.”

So when somebody cuts you off in traffic or tries to get the better of you in a business deal, instead of getting angry, we can look at those as opportunities to grow?

“Yes, you’re right. And be with the moment. First you feel the uncertainty or fear—and there’s not only fear there. There is a sense of being, of who we are, but sometimes there’s something more there within yourself. Greater possibility, potential, awareness, compassion, wisdom. There are skills that you never thought of before. Once you let go of that death concept, you will see new opportunities.”

Tibetan lamas with advanced levels of realization may also engage in a practice called thukdam, entering into meditation when they sense they are about to die. Mingyur told me that his father, Tulku Urgyen, entered thukdam when he was dying and remained there for three days after his apparent death without any visible signs of decay. Richard Davidson is carrying on research into this phenomenon based in India and the U.S, and hopes to report the results in time. Meanwhile, I asked Mingyur how he feels about the apparent disparities in the accounts of Westerners who report back via mediums that on “the other side” there is no evidence of a particular tradition—not Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, or anything else. What they all describe in slightly different language is that souls there move through varying levels of awareness and spiritual growth, but without the sectarian terminology that we use on the Earth plane.

“Awareness doesn’t have a tradition,” he replied. “Awareness doesn’t belong to any religion, so the manifestation of awareness can be anything. It depends on your belief, your past experience, culture, mentality, personality. It can be experienced many different ways; it could be anything.”

If awareness, or the nature of mind, is universal, Mingyur explained, then these traditions, even his own, are simply vehicles to connect to that awareness. So, I asked, it doesn’t matter which vehicle helps you connect to awareness? “Yes, you’re right,” he said. “It doesn’t matter.”

Mingyur’s open-minded approach to teaching dharma has allowed him to reach a new, wider audience, and applies to the way he has organized Tergar, his teaching organization. Based in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Tergar offers annual retreats but reaches many more people through Vajrayana Online, a subscription service that offers in-depth courses taught by Mingyur and his team of American senior instructors.

About a month after our phone interview, when I attended the Path of Liberation retreat described above, I experienced a major upgrade in my own meditation practice. I’d been meditating off and on for nearly 30 years, and following various schools of Tibetan Buddhism for at least 20, but I took the retreat because I felt I wasn’t really getting as much from meditation as I expected—partly because of my inconsistent application, to be sure, but partly from lack of knowledge. My daily practice certainly had helped relieve much of my own considerable anxiety and chronic depression, but I never felt that it reached what I had read and been told about its other benefits.

I signed up for Mingyur’s retreat on an impulse, and even before the week was out I realized I was finally having the experience of meditation I’d been reading about.

The key, according to Mingyur, was not trying to meditate, but also not losing awareness, and at the same time relaxing and letting the glimpses of awareness he spoke about come to rest in the mind.

Maybe that’s what all the classical teachers mean by “effortless effort.” And being in the presence of several hundred like-minded souls, as well as a fully realized teacher, certainly helped.

What I also learned, almost by accident, was that I had been mistaken all along in thinking that meditation in general, and experiencing the nature of mind in particular, would lead to some explosive burst of enlightenment, like taking ayahuasca (as I had done years ago) or sitting zazen for thousands of hours until you achieve satori.

I asked Edwin Kelley, one of the senior instructors—who had begun studying intensively with the forest monks of Burma some 27 years ago and later at the popular Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Mass., before becoming Mingyur’s student in 1998—how long it had taken him, after receiving pointing out instructions, to achieve any reliable level of confidence in his practice. “Oh,” he replied evenly, “I would say about ten years.” I suddenly got how much of a process it was, and that I had to be in it for the long haul.

What I also got is that, in place of the one Big Bang I’d been expecting, the realization process most likely consists of a long string of litte bangs, like the one that hit me speaking with Kelley. And yet, after a week of intensive practice, including several 90-minute meditation sessions and two 2-hour teachings each day, incorporating three full days of being in silence, I felt noticeably different by the end of the retreat. And I still feel a profound sense of being more deeply involved in the path and the practices four months later.

I look forward to meditating every morning, starting before I get out of bed, because I know my depression will lift and I’ll feel better. But an integral part of the meditation practice is feeling compassion for others, so feeling better expands to encompass how I feel about other people, and animals. For someone with a chronic hermit archetype, that’s a big deal.

One last thought occurred to me as I wound up my phone interview with Mingyur. I mentioned that virtually his entire book takes place within the first month of his wandering retreat, which continued for four and a half years following his near-death experience. “You must have a lot more stories,” I urged, “all the things that you experienced during the rest of your retreat that you might write about in time.”

“I don’t have plans to write about that, no,” Mingyur responded. I imagined him smiling on the other end of the line. “Of course,” he added, “I have some good experiences that I want to keep for myself!”

Recently, though, I’ve started hearing rumors that he has begun working with Helen Tworkov again for what could be a sequel about the rest of his retreat. He may not be planning to keep all those other good experiences to himself, after all.

Nothing endures but change, and accepting this has the potential to transform the dread of dying into joyful living.

~ Mingyur Rinpoche

_

An online course called “Dying Every Day: Essence of the Bardos,” based on Mingyur’s new book, In Love with the World, is currently in progress and available with a subscription to Vajrayana Online. The subscription is on a sliding scale, $25 or $50/month. The course runs through the end of October and includes a downloadable course workbook PDF. It can be joined at any time and includes video and audio teachings by Mingyur Rinpoche and two of his American instructors.

A new online course, Awakening in Daily Life: The Bardos of This Life, taught by Mingyur Rinpoche and Tergar instructors, will begin Dec. 1, 2019. At its heart, the bardo teachings are concerned with the core teaching of impermanence, both in life and in death, and with the liberation that comes with recognizing the real nature of the mind in the midst of all that changes.

Learn more at learning.tergar.org

You may also enjoy reading Inside Out: Exploring the Out of Body Experience, by Peter Occhiogrosso