Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Facing cancer, one woman chooses to live fully — which leads to surprising joys, relationships…and even a novel

—

I am a two-time breast cancer survivor, but my story is not really about cancer and its trials. It’s about how cancer taught me that humor, nature, exercise and relationships with both family and “found family” helped me heal and learn to stop living in fear. The strategies that saw me through breast cancer also led me to become a debut novelist at age 71, in better physical shape than when I was fifteen years ago, and more at peace

My first cancer diagnosis hit like a freight train. I was 55 years old, in otherwise good health, and working more than full-time as communications director for a statewide elected official and the sprawling state agency he oversaw. In an instant, everything took a backseat to cancer. There were two surgeries, three months of chemotherapy, seven weeks of daily radiation treatments, and then hormone therapy prescribed for five years. Time went by in a blur.

Cancer itself didn’t shock me. I had no thoughts of, “Why me?” Seriously, why not me? Why was I well-fed and clothed, living with a caring family in a comfortable house on a tree-lined street, with supportive friends and colleagues? Why was I not, say, wandering the desert in Sudan with an emaciated child in my arms?

Gratitude isn’t necessarily the first place you go when receiving a cancer diagnosis, but, despite the sudden-onset fear of death that comes with such news, I knew I was fortunate in every other respect.

That doesn’t mean my mind wasn’t off to the races with fearful images of recurrence. Despite a good prognosis, I secretly believed I had only two or three years to live. My cancer was early stage, but aggressive. I’d read that metastatic recurrence was most likely in the first two-to-five years (not true for my type, but that wasn’t then known). Also, from the time I was in my 20s, I’d lost many loved ones to cancer and at that time knew nobody who was a long-term survivor. The disease had taken both of my parents, my best friend, another very close friend, my first boss, a woman on my staff, three other close colleagues, two ex-boyfriends, and even my occasional housecleaner, also a friend.

I Googled so many medical articles I’m sure I qualify for an internet MD. I’d wake up at 2 a.m. and cut-and-paste the worst-case prognoses, proving to myself that this was it, cancer was my life and there wasn’t much left of it. In retrospect, I see that was my way of trying to gain some control in an uncontrollable situation. So sadly, that’s how I spent many hours in the supposedly last two years of my life — In fear, and obsessing.

Twelve Step programs have a saying for this: FEAR=False Expectations Appearing Real.

Despite that self-inflicted angst, there were points of light that gave me strength. Humor, for one, even in the roughest parts of treatment, I could laugh at myself and see the absurdity in specific moments. (Strapped half-naked to a table getting radiation, while “Boogie Wonderland” blared from a speaker. Trying on some hilariously awful wigs and cancer headgear. The “danger — radiation” sign that cancer patients must pass in order to get treatments that — look out — might cause cancer.) I found books and movies that made me laugh, and I’m blessed with a son and husband who are both hilarious.

Humor relieved tension, took me outside of myself and helped me gain perspective. Without humor, it can sometimes feel as if there’s no hope. And without nature, it’s too easy to get lost in one’s self. Walking among the beautiful trees in my neighborhood, on the beach or in the magnificent Redwoods, never fails to fill my soul. Writing, whether an essay or just a few sentences in a journal, helped to quiet my chattering mind.

During most of my first treatment regimen I worked full time, taking off only those days when I could barely get out of bed. Thoughts began to press in — what to do with what I believed would be my few remaining years? Supportive workplace or not, I couldn’t see spending those precious days in a windowless office, in meetings or press conferences or writing speeches. So, less than two years after my diagnosis, I retired early, having no idea what lay ahead.

I’d spent more than 20 years as a journalist, then a decade in political/policy PR, and decided I wanted to learn how to write stories in my own voice, from my own imagination. At the same time, I wanted to give back, particularly to women going through the frightful early days of breast cancer.

As my strength grew, I began taking short story classes, joined a prompt-writing workshop, and volunteered with a local breast cancer organization’s helpline. Before long, I was also a breast cancer peer navigator (mentor) with UC Davis Medical Center’s breast cancer program.

Some patients wanted only a supportive phone call or two, but with a few others I took notes at oncology appointments, went wig shopping, sat through chemo treatments, talked with their husbands and kids, shared dinner at my home and theirs, and talked for hours about the strange path we’d shared.

With these women I’d have never otherwise known, of different backgrounds, ages and personalities, a special bond developed. We became “found family” for each other.

I began to see myself through their eyes — as a healthy, happy, survivor whose hair had grown back and body had grown strong. Accompanying them on their journeys, watching them grew strong as well, was a powerful, spiritually nourishing experience. Like the protagonist in my novel, I was not one for support groups, but found my own support in offering it to others.

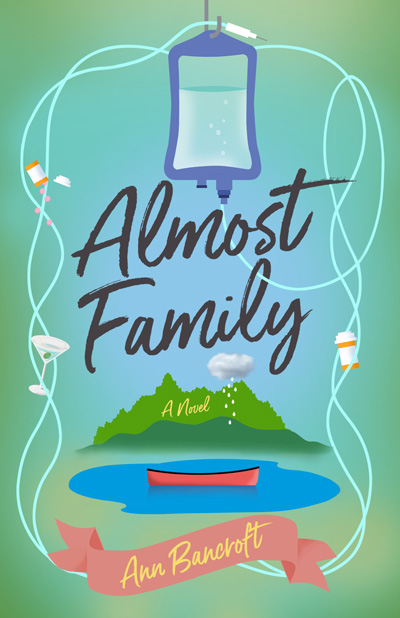

Connecting with others also helped my attitude and perspective. I saw that I was not special; mine wasn’t nearly the worst case. And relating with these women, often with laughter over simple things, lifted my spirits immensely. I began to write, not about them but about characters who meet in a cancer support group and, late in life, develop such intimate bonds, deeper in some ways than the bonds they had with family members. In what eventually became my novel, Almost Family, I wrote about difficult things, but I also used humor in my writing. Creating this story was not only satisfying as a writer, it helped remove me from my own cancer experience. Through writing, my cancer began to feel like someone else’s story.

I’d lived through my two-year feared expiration date. Working out regularly at the gym, spending more leisurely time with friends and family, making it a priority to enjoy the outdoors, I began to feel and look healthier than I had before my diagnosis. My secret new password? “Alive@65!” It seemed conceivable I’d make it to that goal, or even beyond.

Well, age 65 passed, and in the years leading up to it I learned to face up to my fear. I thought, what is the worst thing that could happen? Well, I could die. And then… Guess what! I’m going to die anyway, of something. We all are, and we have no way of knowing when. So why not keep living fully while we’re alive? I saw how the terrible things I’d imagined never actually happened. My worst experiences were in my imagination!

I found that facing mortality is freeing, and helped focus and give power to my life.

Accepting mortality also propelled me to quit procrastinating on things I wanted to do with this time-limited life, including finishing that novel.

Drafts of the novel were awarded, rejected, praised and rejected again, but my cancer experience helped me to not take any of it personally. I had approached the novel with the eyes and habits of a journalist, not yet a novelist, and still had a lot to learn. After initial rejections, I put it on a shelf and began work on a second, completely different story.

Thirteen years after my first diagnosis, I was living happily and my previous bout of cancer rarely even crossed my mind. There was the pandemic to think about, and my weekly writing group moved to Zoom, along with regular online meetings with family and old friends. That time of pushing through isolation in order to stay connected deepened the gratitude for friendships that had grown with cancer.

One day in February of 2021, I put on a mask and went in for a routine mammogram, and another tumor was found. In short order, I had a mastectomy — actually three different surgeries — and the same course of chemo again.

Once again I lost my hair, but the months of treatment were radically different, because I was no longer caught in fear. I knew I’d come through. With the gift of retirement, I had built a stronger community of friendships, meeting outdoors or online at that point. My chosen family of close friends enriched the family given to me by birth and marriage. My creative writing practice was spiritually fulfilling, and physically, though older, I was in better shape than I’d been even fifteen years earlier.

I exercised to stay strong, walking stairs or outdoors three to four miles on most days The day before each chemo session I went on a strenuous hike somewhere beautiful in nature; that made the difference between bouncing right back and laying about sick and depressed like I had the first time.

After my second diagnosis, I pulled that first novel off the shelf and began revising it until I was satisfied it was the story I wanted and needed to tell. Writing it allowed me to put my creative mind to my own cancer experience.

Like my characters, I know that l’ll keep growing until the end of my life, with or without cancer.

I’m now 71, and my debut novel, Almost Family, comes out this Spring. My last cancer experience is three years behind me, and my next novel is about a third of the way done.

Recently, I was at a writer’s conference where on two different panels, authors lamented their ages. “Well, I’m old,” said one. “Fifty-two!” Another said she got her start as a writer late in life — at age 37. I stifled my laughter.

However, when I learned my novel would be published and that I suddenly needed to consider things like author photos and appearing before strangers, I’m embarrassed to say that my first thought was, “should I go back to dyeing my hair?” (Post-chemo, it grew back white). I wondered, will people take me seriously as an older woman author? I quickly realized it doesn’t matter — I have no control over what other people think or what stereotypes they carry. And who would I be kidding? Besides, I’ve grown to like having white hair.

Like most people I know in my age cohort, I don’t feel old, and I don’t buy that being over 60, or 70, or whatever other arbitrary age is determined by society as “elderly,” makes me incapable of pursuing the things I want in life. Particularly when it comes to writing, I believe the more years you’ve lived the more you have to offer. Certainly I have more to learn, more ways in which to grow, and life will continue to throw me some curves. But I’m more adaptable, more relaxed and more open to new experience than I have been at other times in my life.

So I’ll keep writing, because it’s what I do.

You may also enjoy reading Mastectomy & Self Love: How Losing My Breasts Helped Me Love My Body, by Sarah M..