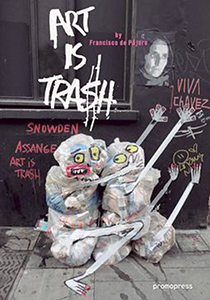

Art Is Trash: The Street Art Of Francisco de Pajaro

—

The Navajo of the American Southwest and the Buddhists of Tibet share similar traditions of creating art that is meant to be ephemeral.

The Navajo create sand paintings that are symbolic representations of stories from their mythology — and immediately afterward, the remains of the painting are taken outside and returned to the earth.

The Tibetans have a ritual involving the creation of Buddhist mandalas, spiritual symbols representing the universe, made from colored sand (actually white stones ground down and dyed with colored inks to achieve the same effect). And as with the Navajo, once the Tibetan mandala is completed it is ritualistically dismantled to symbolize the Buddhist belief in the transient nature of the material world with its endless cycle of life and death.

When I first saw the street art of Francisco de Pájaro, I certainly didn’t make any mental connection to these ancient traditions. I was too busy laughing out loud at the outrageous sense of humor and often rude absurdity that Pájaro conveys by creating art out of garbage he finds on the streets of cities around the globe. In his hands, transparent trash bags filled with empty soda cans are transformed into terrified-looking figures huddled together. A dumpster loaded with useless strips of drywall and construction detritus becomes a fearsome nightmare horse that might be begging for mercy. A discarded mattress wedged against a stanchion conceals a lurking terrorist holding an Uzi, from the barrel of which protrudes… a paint roller dripping with what looks like blood.

This astonishing alchemy of the street began after an unsuccessful exhibition at a gallery in Pájaro’s native Barcelona. Feeling the frustration all too familiar to artists rejected by the conventional art world and its patrons, he found an abandoned wardrobe in the street and painted it with his slogan El arte es basura: “Art is trash.”

The story goes that a bystander started filming what he was doing, and naturally this attracted a crowd. Pájaro soon realized that by wielding a selection of marker pens and acrylics to paint on the trash itself, and using tape to make arms and legs for his figures, he could create three-dimensional works without defacing the buildings or trespassing on “private property.” Challenged by security guards, he pointed out that what he was painting on wasn’t actually private at all, since as trash it was already slated for removal. Empty boxes, wooden slabs, abandoned bathtubs and mattresses inhabited a kind of no man’s land en route to the nearest landfill.

These pieces of trash became the disposable canvases on which Pájaro worked his transitory magic.

Pájaro credits the influence of other Spanish artists, from Picasso to Dalí, and certainly their absurdist humor is apparent. But the grotesqueries he manufactures on the spot — on the run, even — remind me more of another Francisco. Two centuries ago, Goya mixed violence, sexuality, and phantasmagoria to create a memorable art that was often both hilarious and shocking.

According to London gallerist Tommy Blaquiere, who wrote the Foreword to Pájaro’s debut book, Art Is Trash, his work also reflects the influence of the 1980s Spanish comic book series Mortadelo y Filemón by Francisco Ibáñez Talavera (on which a 2003 Spanish-language film of the same name was based). And yet Pájaro’s constructions are even more ephemeral than most comic books. As the garbage trucks appear and noisily begin to haul off Pájaro’s latest creations, I can’t help thinking of those indigenous sand paintings of the Navajo and the Tibetans, meant to be returned to dust not long after they are created. Francisco’s art does more than imitate life; it imitates life and death.

Click an image below to view the gallery:

Learn more about the artist at FranciscoPajaro.com

You may also enjoy reading The Mindful Spaces of Daniel Wheeler by Peter Occhiogrosso